THE SA INFORMAL CITY SEMINAR 2011

The South African Informal City seminar is organised in collaboration with the Johannesburg Development Agency, SA Cities Network, Neighbourhood Development Programme (National Treasury), the National Research Foundation and the South African Planning Institute.

The goal is to set up a platform for discourse around informality and sustainable city development, and to further cooperation, information sharing and positive action between decision makers, practitioners, academics and civil society involved in this field.

The one-day programme covers four themes:

Place

The first session on ‘Place’ will be an engagement on the nature and roles of informal settlements, general lessons and policy reflections. The debate will include some interesting insights into what role informal settlements and property markets play; what works or doesn't work about them, and for whom; what our formal systems (public, private, development) could do to effectively engage in terms of solution seeking; what some future directions/possibilities are; what are emerging research/policy/action questions, and for whom.

Facilitator:

- Sarah Charlton, University of the Witwatersrand

Speakers:

- National Development Plan: Vision for 2030

Prof Philip Harrison, SA Research Chair in Development Planning & Modelling - Informal settlements in Johannesburg: How much do we know?

Marie Huchzermeyer, Aly Karam and Miriam Maina, University of the Witwatersrand - Kya Sands Informal Settlement: Vulnerability and Resilience

Dylan Weakley, University of the Witwatersrand - Study on potential interventions in the small scale rental market

Stacey-Leigh Joseph, National Department of Human Settlements

Informal settlements in Johannesburg: How much do we know?

Marie Huchzermeyer, Aly Karam and Miriam Maina, University of the Witwatersrand

The following is an extract from a draft chapter titled ‘Informal Settlements’ for a forthcoming book on spatial change in Johannesburg edited by Phil Harrison, Alison Todes, Graeme Gotz and Chris Wray. It was presented at the South African Informal City Seminar, 15 November 2011.

Informal settlements have formed an essential part of Johannesburg since its inception, to some extent shaping its development, to a large extent repeatedly displaced by formal development but re-emerging elsewhere. This research focuses on the current informal settlement situation within the municipal boundaries of the City of Johannesburg. It compares the informal settlement data-base of the City of Johannesburg with informal settlements as per the definition adopted by the National Upgrading Support Program (NUSP) (attributed to the Upgrading of Informal Settlements Programme UISP). Central to NUSP’s definition is that an ‘informal settlement’ exists where housing has been created in an urban or peri-urban location without official approval.

The official and political position on informal settlements in Johannesburg is that this form of residence has been ‘mushrooming’ or ‘ballooning’ over the past decade, that there are over 180 and more recently 189 such settlements in the city and that they are largely unsuited for in situ upgrading, therefore requiring relocation. Using NUSP’s definition of informal settlement, which technically excludes municipal transit areas and formal housing developments, we separated actual informal settlements from other inadequate forms of residence which City of Johannesburg includes in its informal settlement data-base (see Figure 1). As a result, the number of informal settlements drops from 189 to 135. The majority of these 135 settlements were formed pre-2000 and no new informal settlements formed after 2003. In this analysis, the percentage of Johannesburg’s households living in informal settlements is currently below 7.5%.

Informal settlements in Johannesburg remain concentrated in an arc along the city’s western periphery, from Ivory Park in the north east past Diepsloot in the northwest, down to Orange Farm in the far south. This pattern must be understood from a view beyond the City of Johannesburg’s boundary line. On the one hand, the continuation of Johannesburg’s up-market suburban core of northern suburbs into the neighbouring Ekurhuleni Municipality to the east means that no informal settlements established themselves on the City of Johannesburg’s eastern boundary. On the other hand, in three large concentrations, City of Johannesburg’s low income housing areas, all with pockets of informal settlement, form part of a much larger agglomeration of such low income development. Orange Farm’s development continues across the Johannesburg border seamlessly into Evaton, Ivory Park into Thembisa, and Ebumandini (to the west) into Kagiso (see Figure 2). A further large low income housing concentration just outside the City boundary is Olievenoutbosch, directly to the north. Only one informal settlement itself crosses the municipal boundary, this is Chris Hani Extension 4 settlement, in an area spanning Ivory Park and Thembisa.

This research shows that growth in informal settlements is mostly punctual (restricted to specific areas) and spatially follows the strongest trends in formal up-market residential expansion with its domestic employment demands. Our finding is also that the majority the informal settlements in Johannesburg are characterized by low density and an orderliness in their layouts. This usually mirrors formal layouts in the surrounding. Low density and orderly layouts make these settlements more amiable to in-situ upgrading. Some, however, are on private land. The City and the Province consider this an obstacle to in situ upgrading.

One of the main findings is that Johannesburg’s informal settlement situation is less dramatic than generally assumed, but also more complex. The analysis challenges political rhetoric, official data and the City’s intervention programs for informal settlements. We call, instead, for a more differentiated understanding of the situation, which, in our analysis, may pave the way for actual in situ upgrading.

The research raises concern less with informal settlement growth than with large concentrations of informal settlement, often dating back to the transition from apartheid to ANC-led government, that have seen little if any improvement over the past decade. This calls into question, not only the suitability of the City’s informal settlement intervention program, but also the rationale behind the City’s spatial investment planning over this period, a theme that is carried through several chapters in this book.

The research raises concern less with informal settlement growth than with large concentrations of informal settlement, often dating back to the transition from apartheid to ANC-led government, that have seen little if any improvement over the past decade. This calls into question, not only the suitability of the City’s informal settlement intervention program, but also the rationale behind the City’s spatial investment planning over this period, a theme that is carried through several chapters in this book.

Kya Sands Informal Settlement: Vulnerability and Resilience

Dylan Weakley, University of the Witwatersrand

This article is a brief summary of a presentation done at the SA Informal City Seminar on 15 November 2011. It is based on or taken directly (in parts) from research undertaken by Dylan Weakley for his master’s degree . The research was funded by the NRF through the provision of a bursary. While this is the case, the views reported in this article do not necessarily represent those of the NRF. More detailed information on Kya Sands can also be found at the website set up as part of the Masters research mentioned above at www.sainformalsettlement.com.

Kya Sands Informal Settlement: Limited Government Action Related to Resilience

Kya Sands is an informal settlement located in Region A of the City of Johannesburg (CoJ). It is informal as per Karam and Huchzermeyer’s definition of informal settlements being those settlements that were not planned by nor have formal permission to exist from government. Having said this, the definition is a bit crude in terms of this work and parts of the settlement may not fit this definition entirely. This is in that some residents were placed in certain sections of the settlement by the City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality, arguably giving those residents permission to live there.

Professional Mobile Mapping reports that the settlement is made up of 16,238 people living in 5,325 dwellings . If accurate, this is a very high number, giving a population density of 104,089.7/km2 (1,040.9/ha), similar to that of Kibera Informal Settlement in Nairobi, Kenya .

On 15 November 2006, a mayoral road show visited Kya Sands informal settlement. These road shows are a form of public participation that allow residents to communicate directly with the top management of the CoJ. From this visit, and due to the "appalling conditions that were found on site" the mayor set up a task team made up of the city's Development Planning, Urban Management and Housing departments to come up with long and short term strategies to address the "health and safety risks confronting the community" .

While short term interventions have been fairly successful in delivering basic services, no long term interventions have been implemented to date with no action in sight. This has resulted in numerous service delivery protests in Kya Sands, with the most recent coinciding with Human Rights Day, 21 March, 2012 . This is a tangible example of Huchzermeyer’s argument that despite progressive policy being in place regarding informal settlement intervention (such as in-situ upgrading) effective responses to informal settlements by planning authorities are limited.

The work hypothesises that one reason for this (among others proposed by Huchzermeyer e.g. ), relates to the type of resilience displayed by formal government structures, as well as their perception of resilience. Formal planning authorities display the opposite type of resilience to informal settlements (if indeed it could be represented on a simple continuum). Government structures show mainly equilibrist resilience, making them stable and not easily knocked off their state of stability. At the same time however, they lack the type of resilience shown by informal settlements being evolutionary/transformative resilience or adaptability to the changing urban context, shown by their limited success in effectively engaging informal settlements.

Also, just as planning authorities display equilibrist resilience; it is their mind-set of what resilience is. Huchzermeyer describes this by saying "[t]he inherent, although fragile, abilities of informally established settlements to respond to the demands of urban poverty have been officially ignored" . By failing to recognise the evolutionary resilience displayed by informal settlements, planning authorities inherently view informality as vulnerability. Here, the first step in engaging informal settlements is usually some sort of formalisation. This is an attempt by planning authorities firstly to make the two more compatible with one another (the authority and informal settlement) to allow engagement and secondly to start building the type of resilience that formal structures can relate to.

Thus, this research argues that in order for planning authorities to effectively engage with informal settlements, the inherent resilience contained by these informal settlements can no longer be ignored. To this end, the research looks to investigate this resilience in Kya Sands and report it in a way that planning authorities can respond to. At the same time, it is clear that vulnerability to certain hazards exists in informal settlements, and that this too needs investigation, with findings guiding authorities’ response.

Data regarding vulnerability and resilience in Kya Sands was collected through an interview process with residents in January 2012. Sixty residents were interviewed in total in interviews lasting an average of half an hour each. These were systematically geographically spread across the settlement in order to allow responses to be located in space and mapped. Findings from the work are currently being written up, and it is hoped that the thesis will be completed before the end of 2012. Preliminarily, findings indicate that the main resilience Kya Sands provides its residents is access to the city that they are effectively formally excluded from. This access is largely to the economic opportunities of the city, but includes other amenities such as access to healthcare and schooling and to social networks in the city. Kya Sands provides a viable entry point to the city for the poor that is actually affordable (sometimes free) and not limited by regulatory systems. At the same time, dangers such as crime, fire and flooding and poor living conditions are realities in the settlement. So while these need to be addressed, the process of doing so should not erase the resilience that the settlement provides for its residents, and the reasons it was established in the first place.

National Development Plan: Vision for 2030

Prof Philip Harrison, SA Research Chair in Development Planning & Modelling

Background:

The President appointed the Commission in May 2010 to draft a vision and plan for the country. The Commission is advisory - only Cabinet can adopt a development plan.

On 9 June 2011 we released a diagnostic document and elements of a vision statement; and on 11 November, we release the vision statement and the plan to the country for consideration.

Values of our Constitution are entrenched in the plan, such as:

- Social solidarity and pro-poor policies

- Non racialism, non-sexism (SA belongs to all who live in it)

- The need to redress the ills of the past

Thandi’s life chances:

Thandi is an 18-year old girl who completed matric in 2010. Let us look at her life chances:

There is a 13% chance that Thandi will get a pass to enter university. BUT she is an African female so, for Thandi, the chance of getting a university pass is actually 4%.

Let us assume that Thandi passed matric but did not go to university:

- Her chances of getting a job in the 1st year are 13%

- Her chances of getting a job in the first 5 years out of school are 25%

- Her chances of earning above the median income (about R4 000 a month) are 2%

- Chances are that Thandi will not get a job in the 5 years after school, and for the rest of her life she will receive periodic work for a few months here and there

- Chances are that Thandi will remain below the poverty line of R418 a month for her entire life until she finally gets a pension.

Figure 1: School enrolment and matric passes 1999 to 2010

Grade 1: Reflects over enrolment

Grade 12: 46% drop out rate before grade 12

School leavers: 13% get exemptions, 12% diploma entrance

1. The Diagnostic:

2. The Plan:

The broad diagnostic in the NPC was carried forward into a more specific diagnostic in relation to spatial arrangements which is structured around five story lines.

Transform urban and rural spaces:

- Move from directly providing houses to:

- Fixing the gap in the housing market

- Strengthening local and community-based planning capacity

- Facilitating provision of a full range of housing types

- Ramp up public transport infrastructure significantly

- Support local incentives to move jobs to townships

- Shift more resources to upgrading informal settlements

- Introduce a mechanism to capture part of the increased value of public investment for the public good

- Facilitate security of tenure (especially for women) in rural areas

- Address fragmentation in spatial planning

Five story lines in relation to space:

- Spatial dislocations at a national scale

- The challenges facing towns and cities

- The uncertain prospects of rural areas

- Challenges of providing housing and basic services and reactivating communities

- Weak spatial planning and governance capabilities

-

Spatial dislocations at a national scale:

- A relatively well balanced spatial structure in one respect but deeply dysfunctional in another

- Entrenched spatial patterns that require multi-dimensional responses

- Some shifts since 1994 (e.g. the rising prominence of Gauteng)

- The environmentally destructive nature of spatial development patterns

- Urban-rural dependencies

-

The challenges facing towns and cities:

- Complex trends – centralisation and decentralisation (opportunities at all scales)

- Slower urban growth

- The ‘ring of fire’ around the metros

- Little progress in reversing apartheid geography

- The major shift to public transport is yet to happen

- Ecological limits to growth emerging

- Towns and cities are not productive enough (even metro growth is disappointing)

-

The uncertain prospects of rural areas:

- The importance of rural areas understated in the national accounting system

- South Africa’s peculiarity – a very small percentage actively involved in agriculture

- Agriculture’s prospects in the short to medium term uncertain but rural areas cannot indiscriminately be written off as significant growth dynamics and potentials in certain areas

- Key spatial issues include: rural differentiation, infrastructure type and location, spatial dimensions of land reform, Local systems of food production and distribution

-

Challenges of providing housing and basic services and reactivating communities:

Since this story line relates specifically to the theme of the workshop, it is elaborated below in more detail than the others.

Citizens in South Africa do engage the state in various ways, including through democratic process, the use of the media, and the now common ‘service delivery protests’. However, the model for service delivery entrenched after 1994 has not incentivised active participation in all areas of development and runs the risk of producing a dependent and inactive citizenry. Households and communities have become passive recipients of government delivery. Many It is fair to say that many households are no longer actively seeking their own solutions or finding ways to partner with government to improve their neighbourhoods. Although government has a clear responsibility to provide services, alternative policies of service provision are needed that satisfy popular expectations, while building active citizenship and expanding citizen capabilities.

The problem of dependency is most severely represented in housing. Many households have benefited from houses provided by the capital subsidy programme, but the harsh reality is that the housing backlog is now greater than it was in 1994. New approaches are needed, with individuals and communities taking more responsibility for providing their own shelter. but with the state still playing an active role in supporting household initiative and in developing the public environments and the public infrastructure that is needed to produce sustainable neighbourhoods.

The capital subsidy programme has had unintended consequences and re-enforced apartheid geography. Financing has mostly focused on individual houses and ignored public spaces. To stretch limited subsidies, public and private developers often sought out the cheapest land, which is usually in the worst location. The capital subsidy regime has also generally resulted in uniform housing developments, which do not offer a range of housing and tenure types to support the needs of different households. It has also failed to meet the needs of a large segment of the population that requires rental houses, forcing many into backyard shacks on private properties.

The commission is of the view that public funding should therefore be directed towards the development of public infrastructure and public spaces that would significantly improve the quality of life of poor communities who cannot afford private amenities. Increasingly, government should take on an enabling role in relation to housing. Some form of subsidy may still be required, as the vast majority of South Africa’s population is unable to access private financing, but this subsidy should also support community and individual initiatives and the development of well located sustainable communities.

The commission acknowledges the positive direction that human settlement policy has taken since the introduction of the Breaking New Ground policy in 2004. The policy suggested “utilising housing as an instrument for the development of sustainable human settlements, in support of spatial restructuring”. Breaking New Ground argued forcefully for better located housing projects, more diverse housing forms, informal settlement upgrading, accrediting municipalities for housing delivery, and linking job creation and housing. This approach was reinforced recently with the creation of a Department of Human Settlements and with the President’s Delivery Agreement on ‘Sustainable Human Settlements and Improved Quality of Household Life’ (Outcome 8).

Particularly important elements of Outcome 8 are: the commitment to upgrade 400 000 households in well located informal settlements with the assistance of the National Upgrading Support Programme (NUSP); the emphasis on affordable rental accommodation; and, the mobilization of well located land (especially state-owned land) for affordable housing. The commission believes that the full implementation of Outcome 8 will make a major contribution to shifting housing delivery from its focus on providing a single form of accommodation to meeting a diversity of housing needs.

However, there are further shifts that are needed and there are urgent matters relating to implementation that must be resolved:

- Target setting in municipalities and provinces still focuses mainly on delivering numbers rather than dealing systematically with the deficiencies in the implementation system and producing viable human settlements.

- The capital subsidy remains a very limited instrument for achieving objectives of human settlement strategy, especially the need for better located settlements with a diverse range of housing and tenure types, and high quality public environments.

- Despite the new focus on informal settlement regularization and upgrading at national level, there is still a high level of ambivalence towards informal settlements across spheres of government, and the capacity and implementation mechanisms to achieve the national objectives are still poorly developed locally.

- Despite a BNG emphasis on affordable inner city housing as part of a broader urban renewal strategy, municipalities have continued to focus attention on housing developments on ‘greenfields’ where targets are more easily met. Inner cities have continued to develop as a mix of slum-lording for the low income sector and exclusive developments for the wealthier in scattered pockets of urban regeneration.

- Financing and regulatory arrangements have hindered household mobility, fixing residents within specific places at a time when the spatial circumstances of households (e.g. places of work and schooling) change regularly.

-

Weak spatial planning and governance capabilities:

- South Africa’s intergovernmental system of spatial planning has been slow to develop and coordination has often been poor

- Impossible to undertake cross-border planning

- Spatial planning is dispersed across national ministries

- Provincial land-use management functions overlap with municipalities, creating confusion and conflict

- Ambiguity and contest around the developmental role of traditional authorities

- Sound spatial governance requires strong professionals and mobilised communities

Six major proposals

- PROPOSAL 1: Develop a national spatial framework

- PROPOSAL 2: Strengthen the spatial planning system

- PROPOSAL 3: Start a national conversation about cities, towns and villages

- PROPOSAL 4: Bolder measures to make sustainable human settlements

- PROPOSAL 5: Support rural spatial development

- PROPOSAL 6: Build an active citizenry to rebuild local place and community

- Develop a national spatial framework:

- A national spatial fund

- A national observatory for spatial data assembly and analysis.

- An interdepartmental spatial coordination committee in the Presidency

- An approach premised on spatial differentiation

- Spatial targeting

SPATIAL TARGETING

- National competitiveness corridor

- Nodes of competitiveness

- Rural restructuring zones

- Resource critical regions (ecosystem lifelines)

- Special intervention areas:

- Job intervention zones

- Growth management zones

- Green economy zones

- Strengthen the spatial planning system:

- A major system review followed by legislation (by 2016) to resolve the current fragmentation in the planning system

- Translate plans into spatial contracts

- Provision for cross-boundary plans

- City-region wide co-ordination of planning

- Possible regionalisation of planning and service delivery

- Start a national conversation about cities, towns and villages:

- ‘Unleashing citizen’s popular imagination, creative thinking and energies is fundamental to tackling the formidable challenges and opportunities that settlements face’.

- ‘To achieve this, the media (radio, television, newspapers and new social media) and civil society organisations could stimulate a conversation at national and local levels about neighbourhoods, towns and cities’.

- ‘Broad debates around urban and rural futures should be complemented with focused conversations on specific issues’.

- Bolder measures to make sustainable human settlements:

- A coherent and inclusive approach to land

- Radically revise the housing finance regime

- Revise the regulations and incentives for housing and land use management

- Recognise the role played by informal settlements and enhance the existing national programme for informal settlement upgrading by developing a range of tailored responses to support their upgrade

- Support the transition to environmental sustainability

Some of the more specific measures may include:

- Move from directly providing houses to:

- Fixing the gap in the housing market

- Strengthening local and community-based planning capacity

- Facilitating provision of a full range of housing types

- Ramp up public transport infrastructure significantly

- Support local incentives to move jobs to townships

- Shift more resources to upgrading informal settlements

- Introduce a mechanism to capture part of the increased value of public investment for the public good

- Facilitate security of tenure (especially for women) in rural areas

- Support rural spatial development:

- Guiding principles for provision of infrastructure in rural areas

- Land reform programmes should reflect the importance of location and connectivity for farm viability.

- Investigate and respond to shifting settlement patterns

- Small town development strategy

- Spatial interventions to support agricultural development

- Build an active citizenry to rebuild local place and community:

- Properly funded, citizen-led neighbourhood vision and planning processes

- Public works programmes should be tailored to community building and local needs

- Citizenship education and training to strengthen community organisation, planning and project management skills and competences

- Local arts, culture and heritage precincts

- Forums for dialogue and liaison should be established at neighbourhood and municipal levels (e.g. to address migrant exclusion)

Conclusion

These proposals are contained in a draft plan that has been presented to the public and will be the basis of intense dialogue with stakeholders. We have an opportunity over the next few months to improve the analysis and improve the plan, and we request all individuals and agencies that have an interest in spatial transformation and human settlement to make comments. We need to get this right.

Study on potential interventions in the small scale rental market

Stacey-Leigh Joseph, National Department of Human Settlements

Presentation Outline:

1. Background and motivation

2. Developing a national rental research agenda

3. Definition and Scope for small scale rental research

4. Current context

5. Case studies

6. Preliminary reflections

7. Expected outcomes

Introduction

The importance and relevance of the rental market is increasingly being recognised in South Africa. However, it remains a poorly understood and under emphasised component of the country’s housing and human settlements response. Though rentals are found all over the world and are occupied by people from a range of sectors in society with varying levels of income, the rental market in South Africa enjoys very limited attention and recognition. Rentals in the higher income private market are considered the norm and a vital part of the housing industry, while rentals in lower income, informal or illegal areas have been an invisible aspect in South Africa’s housing response.1 Yet, it is impossible to ignore the reality any longer of this highly complex sector that is playing a critical role in South Africa’s burgeoning and growing economy and housing market.

As with all housing and shelter related issues in South Africa, the small scale private rental market is nuanced, complex and challenging and will require an approach that takes these aspects into consideration. This research aims to look at the potential opportunities in the rental market that can contribute towards the imperative to develop accessible, affordable and reliable shelter options. While not currently a formal component of government housing policy, the small scale rental market is one area where there is a large amount of potential for scaled up delivery of appropriate shelter, within the context of government’s current scope of housing and settlement delivery in poorer communities, particularly in cities and towns. This study mainly attempts to answer the question of whether or not government should intervene in a specific component of the small scale rental market (backyard rentals) as this is increasingly being identified as a key challenge for particularly the larger municipalities to respond to. In the absence of national policy and guidelines on how to respond to the reality of informal backyard accommodation, these municipalities have attempted to develop their own interventions. The study will reflect on these interventions, the lessons and experiences and extrapolate relevant recommendations for national government on what its response could entail.

1. Background and motivation

South Africa’s current housing backlog - approx 2.4million

Households in rentals – 2.4 million (21% informal)

Rental is becoming the ‘’preferred’’ option both in formal and informal markets

Small scale rental market delivery at scale is on par with government’s provision of subsidised housing

Provides alternative shelter in a complex, nuanced and challenging context

2. Expanding our understanding of the rental market: Developing a national rental research agenda

The Research Directorate within the Department of Human Settlements understands that there is a range of rental types:

a. Rental in informal settlements

b. Inner city rentals

c. Small scale rentals (informal)

d. Social housing

e. Community residential units

f. Municipal rental stock

g. Rent to own

h. Higher end small scale rental

Proposed steps

Overarching framework that will inform a rental programme within DHS;

Development of individual research projects each focussing on the different rental typologies;

Partnerships with municipalities to implement pilots informed by research;

Development of national policy framework and strategies to address various types of rental in SA

This study aims to look at one component of the small scale rental market, namely backyard rentals, and will be one of the individual research projects on the different rental typologies.

3. Definition and scope for small scale rental research

Definition of small scale rental to be addressed

Rental in an informal settlement (undergoing process of regularisation, upgrade )

Renting an informal structure in a formal area

Renting a formal room in a formal area through both informal and formal arrangements

Inner city rental

Scope of study is to address the following:

Should government develop a formal response/intervention to backyards?

If so, what should this look like?

How will this tie in with the current human settlements response?

How will the response/intervention be implemented and what are responsibilities of different spheres?

4. Current context

Despite the existence of numerous policies addressing rental, there is none focusing on informal small scale rentals.

The State tends to focus on home ownership but, for many, rentals are not transitory or temporary – instead they are permanent/long term.

Rental accommodation is considered relatively safe compared to shelter in informal settlements.

The reasons for the massive growth in this market are:

Some access to services

For some only option (incl. non qualifiers, foreign nationals etc)

Generally well located

Sense of tenure security and flexibility

Income for landlords

The challenges faced by tenants and landlords are:

Tenant-landlord relationships

Insufficient access to services and opportunities

Quality of dwelling not always up to standard

Invisibility of backyarders and other users of informal rental options

Factors influencing ability of landlords to formalise or capitilise on opportunities afforded by rental

5. Case studies

Four case studies have been selected: Gauteng and the Western Cape Provincial Governments; and the Cities of Cape Town and Johannesburg.

Gauteng Provincial Government

Introduced pilot programme in 2009 focusing on the upgrade of backyard shelters.

Pilots raised a number of key challenges including shortage of skilled labour, shortage of land and space for upgrade, and insufficient beneficiary education.

The most important challenge experienced was the displacement of tenants after upgrading.

Upgrading did not address the issue of improved access to services.

‘’Double’’ subsidy to landlords who used structure for their own purposes.

Western Cape Provincial Government

Proposed a provincial pilot backyarder programme.

The focus was on ensuring that a percentage of backyarders wasprioritised for new housing.

This initiative drew from the Gauteng programme – subsidy to landlords for upgrade of existing backyard shelters.

Emphasis on compliance in terms of minimum building norms and standards.

Included consultative process with backyarders and emphasis on protection of tenants against displacement.

Following a legal review, the proposed pilot was not implemented due to cost, compliance issues and concerns that it might encounter the same challenges as Gauteng.

City of Cape Town

Proposed intervention strategy to respond to the issue of backyard accommodation connected to city rental stock.

Intention further to improve the conditions in which backyarders live, access to health, safety and services and to introduce measures to protect tenants against arbitrary evictions.

Also focused on the need to recognise the informal rental market as existing alongside government interventions/responses to shelter.

Includes a survey of the current number of backyarders and instituting measures to improve access to basic services including long term plans to upgrade bulk infrastructure.

Potential limitations: only focusing on city rental stock and the study only looks at backyards and not other forms of informal rental.

City of Johannesburg

Faced with increasing pressure to address the issue of backyards and other forms of informal rental, the city has drafted a document focusing on small scale landlordism.

The proposed strategy is to develop an approach to recognise the informal rental market and identify the needs of both landlords and tenants.

The intention is to create an enabling environment for backyard accommodation to grow – through the facilitation and mobilisation of finance.

Incentives for landlords to upgrade structures.

Potential limitations: risk of falling into same trap as Gauteng and, by only focusing on backyards, also possibility of missing opportunity to respond to various types of informal rentals.

6. Preliminary reflections from case studies

Understanding the demographics and motivations within the small scale rental market is extremely important;

Engagement with communities is essential;

More education and awareness raising is necessary (amongst tenants, landlords and policy makers);

Location and access remain critical factors affecting decisions about where people live;

Backyarders and others within the small scale rental market (particularly at the lower, informal end) feel ‘invisible’ and not adequately consulted;

Expanding waiting lists (for housing), without recognising and harnessing the potential of the rental market, is not sufficient;

Improved structures and access to services is critical and interventions to address this should be an important first step;

Government cannot always be an implementer and understanding its enabling or supportive role is important (eg. In terms of providing policy guidelines, regulation where necessary and developing instruments to support the small scale rental market, and engaging with lenders to provide financial support products);

Reviewing municipal by-laws is one way of attempting to create a more enabling environment to support small scale landlords;

Bulk infrastructure investment and upgrading is another important intervention to support this market.

7. Expected outcomes

Partnership with metros and provinces to support and ‘regulate’ the small scale rental market.

Proposed rental pilot project with one metro to test an alternative response to supporting the small scale rental market.

Framework to inform small scale rental policy and potential national response.

Conclusion

This study is one step in a long term process aimed at improving our understanding and recognition of the rental market in South Africa. The study, together with a number of additional studies all focus on the various typologies of the rental market, will form part of an overall rental research agenda and framework currently being developed within the Research Directorate of the National Department of Human Settlements. It is envisaged that this research will over time inform a detailed and comprehensive human settlement response at National level that recognises and supports the rental market and maximises the opportunities for shelter that it presents.

Movement

In South African cities the majority of commuters are served by a relatively unregulated transit system that includes walking and catching a minibus taxi. There is little infrastructure to support these informal transit options, and there is sometimes conflict between informal transit operators and formalised services like bus and commuter rail operations; and often tension between informal operators and private car users.

There is a need to ask questions about how best to make space and provide infrastructure for pedestrians and other non-motorised transport modes in our cities. Tanya Zack will discuss her research about the trolley-pushers who are a key part of the waste recycling industry in Johannesburg; and Andrew Wheeldon, from Benbikes, will share his experience of promoting cycling as a mode of transport in Cape Town.

This seminar also presents an opportunity to think about South African cities in the future where movement systems are more sustainable and integrated. Richard Dobson from ‘Working for Warwick’ will explain how this strategic transit hub in Durban has included informal sectors of the economy through participative development and operating strategies. Finally, Thabisho Molelekwa, spokesperson for the SA National Taxi Association, will share the taxi industry’s experience of shifting from informal and unregulated operational models to more formal transport services like the Rea Vaya bus concession in Johannesburg and the Santaco airline that is operating a service from Johannesburg to the Eastern Cape.

Each presenter will discuss the opportunities and challenges presented by informal movement systems, and share experiences and lessons about how to take advantage of opportunities and confront problems in this space.

Facilitator:

- Melinda Silverman, University of the Witwatersrand

Speakers:

- MOVEMENT: the Bicycle

Andrew Wheeldon, Bicycling Empowerment Network - Working and living in Johannesburg: Insights into informal recycling

Tanya Zack, Town planner and researcher

MOVEMENT: the Bicycle

Andrew M Wheeldon, MSc - Bicycling Empowerment Network

www.benbikes.org.za

“Overcoming poverty is not a gesture of charity. It is an act of justice. It is a protection of a fundamental human right, the right to dignity and a decent life.”

- Nelson Mandela, 2005

"Every time I see an adult on a bicycle, I no longer despair for the future of the human race."

- H. G. Wells

Since c.1865 the bicycle has been a powerful innovation in movement by providing Mobility and Access for all. Democratic freedom, without access, is not freedom at all.

The long bike ride to freedom requires innovative techniques, partnerships, creative thought, reaching out to one another, and the enhancing of communities.

Bicycle mobility enables poverty reduction by offering opportunities. Improved bicycle mobility in both rural and urban areas results in:

- increased social cohesion

- greater access to food, clean water, education and employment opportunities

- potentially reduces the negative impact of motorised transport on the environment

- facilitates a greater sense of our SA community

- we can see, smell, touch and feel the area through which we travel

- and, as South Africans, we can learn so much more about one another

We can do this by building a model of community sustainability.

We also need to measure the extent to which the increased sustainable access/use of the bicycle as a form of mobility affects:

- Economic poverty

- Lower cost of mobility

- Environmental poverty

- Cleaner air, access to water

- Societal poverty

- We move with one another

Challenges to movement

- distance

- time

- cost

- infrastructure

- weather conditions, topography

- comfort and style

- accessibility

However...

- bicycles are low cost, efficient, healthy and more convenient than one would think

- bike paths, sidewalks, parks and public transport facilities are members of the same family, and distant cousins of private vehicle freeways and roads

- if we plan the movement and mobility of all South Africans based on the needs of those most at risk, not the convenience of those most privileged at the expense of others, we will be planning truly democratic cities for all...

A brief history

Industrial transport & communication timeline:

- 1771 canals and waterways

- 1829 railways

- 1875 rail, port, shipping

- 1880 bicycles the chosen individual mode

- 1890 cars (bikes alone only had ten years)

- 1908 mass autos, electrification, radio

- 1971 telecommunication, IT, micro-chip

- 2005 renewable energies and transport

- 2015? bicycles are the mass mobility of all

What has the motor car done?

- The first documented fatality from a car accident occurred in Crystal Palace, London on 17 August 1896 when Bridget Driscoll (UK) walked into the path of a vehicle moving at 6.4 km/h (4mph)

- In the 115 years since, the motor vehicle in its various forms has been responsible for 100m+ deaths globally

- This is close to all the deaths in all the wars of the 20th century – estimated to be 160-200 million.

BEN South Africa

Our organisation was established in 2002 as a Civil Society Organization for public benefit. We imports used utility bicycles from Europe, China, US, Canada, Australia, and the UK.

BEN’s mandate is to:

- establish Bicycle Empowerment Centres (BEC’s) and train managers

- Train school children and adults in safety, skills, and the culture of using bikes

- Distribute bicycles to low income areas

- Facilitate expert exchange programs

- Advocate for bicycle infrastructure

- Inform policy development in Mobility

BEN has established partnerships with the Netherlands-based Interface for Cycling Expertise (I-CE) and the Shova Kalula (Pedal Easy) project of the South African National Department of Transport (NDoT), as well as the cities of Cape Town, Tshwane and Johannesburg.

NDoT’s Shova Kalula programme aims to address the issue of the mobility of children. Of the 13m + school learners in SA:

9m + walk to school; while

3m + walk more than 1 hour per day to school – resulting in absenteeism and fatigue.

BEN has been tasked with the programme assessment and the delivery of one million new bikes, supported by the Department of Education, to assist the travel of learners to school.

To date, the BEN Bicycle distribution includes:

Bicycle Empowerment Centre’s (BEC’s)

Schools – Primary and Secondary

Corporates/ Companies/ NGO’s

District Health Care Programs

Municipality staff (Transport, LA21 etc.)

DoT (Shova Kalula), with BEN as a service provider

Events such as Car Free Days; Bike to Work Days, Redhill Challenge, bike counts and bike park day

Involvement in the Tour d’ Afrique; Cape Argus Cycle Tour; Cape Epic, 350.org, and Big Ride In Day.

At the Velo Mondial 2006, economist Margaret Legum observed, on the role of bicycles in tomorrow’s economy:

“The history of labour arrangements shows a shift from slavery to serfdom, and to employeeship – broadly comprising people working for others; there is much evidence to suggest we are now moving to a new phase where work will comprise livelihoods rather than jobs, when people will work for themselves. The bicycle, as a means of transport, fits perfectly into this paradigm and, by its very nature, is profoundly democratic.”

Bicycle Empowerment Centres

The goals of BEN’s Bicycle Empowerment Centres (BEC’s) are:

- An independent projects within every 5km radius

- Unemployed, semi-skilled project managers trained and set up with businesses – to sell and repair and train

- Training includes basic accounting and finance, bike maintenance, safety skills, project management, community liaison

- Stock of bicycles + tools for the ‘container’ workshops

- Linking of BEC’s with surrounding schools, organisations, infrastructure projects, tourism

- To create a bike neighbourhood in your community.

To date, seventeen BEN Bicycle Empowerment Centres are having a positive impact on the lives of children and adults in the communities in which they are situated, through:

- Bicycle training at schools:

- Schools based and Adult training

- Bicycle maintenance skills

- Bike road safety skills

- Learning to ride for the first time?

- Correct clothing - for comfort and to look cool

- Acceptance of peers

- School route map training:

- Safe routes to school;

- Knowledge base – distances and time

Home-based Health Care Workers: with bikes, care workers’ visits have increased from 7 to 18 patients a day.

- Policy and planning:

- Workshops to establish safe bicycle infrastructure

- Cape Town (BEN/I-CE MOU 2007)

- Pretoria/Tshwane (BEN/I-CE MOU 2008)

- Johannesburg (BEN/I-CE MOU 2009)

- National Dept of Transport: policy advice

- BEN CSO consulting

- NDoT policy framework guidelines

- City bicycle distribution programs

- Linking planning and distribution projects

Conclusion

True democratic cities cater for those that are most at risk – be they economically, physically or otherwise challenged – in a dignified, friendly and welcoming manner. This makes for a fair, free, democratic and equitable city. The greater the gap of privilege and advantage provided for those with economic or social power over those without, the greater the inequality of the society. The bicycle is one of the brilliant inventions of the past 125 years that brings equality to society, that allows us to both move about and meet one another as equals, whilst demonstrating our compassion and care for the environment in which we live. With the simple and humble bicycle we are able to care for the environment, our health and for one another. It allows us all to be able to truly say ‘this is my city, place, environment - I can see it, breath it, smell it, and live it – and I can move freely and democratically about it’.

Working and living in Johannesburg: Insights into informal recycling

Dr Tanya Zack and Sarah Charlton, Johannesburg, 2011

“The world’s 15 million informal recyclers clean up cities, prevent some trash from ending in landfills, and even reduce climate change by saving energy on waste disposal techniques like incineration” (Chaturvedi 2009).

Informal recyclers1 comb the dustbins and sidewalks of residential and commercial neighbourhoods in Johannesburg for selected solid waste items with resale value which they load onto makeshift trolleys. On foot and with sheer muscle power they pull their loaded carts for many kilometers through the streets to privately owned buy-back centres where the waste material is weighed and sold.

Recyclers operate independently of labour regulations and protection, without employee benefits, using improvised transport, and frequently - inadvertently - contravening by-laws and city rules in their living and working activities. But they are intimately entwined with the formal, recognized systems of urban life: essential suppliers to registered recycling businesses, intense users of city roads, sidewalks and public spaces, specialised reclaimers competing daily with the crude appetite of the City’s Pikitup trucks.

The lives of recyclers reflect a wide variety of circumstances. Many recyclers sleep in conditions that are outside of formal residential accommodation.

Table 1: Informal recyclers’ nightly accommodation. Non-formal accommodation column 3, ‘rough sleeping’ column 4. (research conducted in 2009 by students in the course ARPL 3013 at the University of the Witwatersrand, School of Architecture and Planning)

| Interviewee | Nightly accommodation | Non-formal accomm. | Rough sleeping |

| 1 | Shack in Orange Farm | X | |

| 2 | ‘In the bush’ close to where he is likely to get waste | X | X |

| 3 | In the open veld (grass) behind Kentucky Fried Chicken outlet | X | X |

| 4 | In a warehouse in Faraday | X | |

| 5 | In a parking lot in Braamfontein | X | X |

| 6 | In a shack in an informal settlement in Booysens | X | |

| 7 | In an park located behind a large dumpster | X | X |

| 8 | Under the freeway bridge in Newtown | X | X |

| 9 | Orlando East (type of accommodation not clear) | ||

| 10 | On the pavement next to the depot in Bryanston | X | X |

| 11 | On the pavement next to the depot in Bryanston | X | X |

| 12 | Room in a flat in Doornfontein | ||

| 13 | In the basement of a building in Hillbrow | X | |

| 14 | At the taxi rank in town | X | X |

| 15 | In a park in Plein Street | X | X |

| 16 | At the recycling depot | X | X |

| 17 | Unoccupied house in Brixton | ||

| 18 | Flat in Johannesburg CBD | ||

| 19 | In a homeless shelter on Kerk Street in town | ||

| 20 | Under the bridge in Newtown | X | X |

| 21 | Under the bridge in Newtown | X | X |

1 An activity known by other names elsewhere such as ‘binning’ (Gutbertlet et al 2009) or ‘reclaiming’. In Brazil recyclers are known as ragpickers or catadores de lixo( da Silva et al 2005).

Many of the recyclers who sleep rough in the inner city go to homes elsewhere in Gauteng, at weekends or several times a month.

Table 2 below lists nightly as well as other accommodation used weekly or monthly, or visited less frequently (adapted from Bickford, Shapurjee, Ramokgopa, Raymond 2009).

| Interviewee | Nightly | Weekly or monthly | Longer term |

| 1 | Shack in an informal settlement in Orange Farm | Bloemfontein (whenever has money) | |

| 2 | ‘in the bush’ close to where he is likely to get waste | KZN(last went in 2007 due to lack of money) | |

| 3 | Open veld behind KFC in Glenanda |

|

Mpumalanga (doesn’t go back by choice) |

| 4 | Vacant warehouse in Faraday with other people | RDP house in Protea Gardens, Soweto (‘once in a while’) | Nqutu, KZN |

| 5 | Parking lot in Braamfontein with girlfriend and friends. Occasionally food and shower at the Recreation building in Hospital Street, Braamfontein | Shoshanguve(every week) | |

| 6 | Shack in informal settlement in Booysens (with 3 children) | Government subsidised house in Tsakane, Springs (every month) | |

| 7 | ‘in the bush’ – in a park located behind a large dumpster | Escort(once or twice a month) | Mozambique |

| 8 | Under the bridge in Newtown | House in Dobsonville, Soweto with siblings (every weekend) | Osizweni, Newcastle |

| 9 | Orlando East | Mashaying. Fryburg, Free State | |

| 10 | Street alongside the depot in Bryanston | Orange Farm (every weekend - Friday to Monday morning) | Lesotho |

| 11 | Pavement next to depot in Bryanston | Backyard shack in Kaldevin rented from a friend for R250 (month end and public holidays) | Free State |

| 12 | Shared room in a flat in Doornfontein | Lesotho (every 2 months) | |

| 13 | Basement of a building in Hillbrow (with other recyclers) | Shack in Diepsloot (every weekend) | Zimbabwe (every December) |

| 14 | At the taxi rank in town | Komatipoort, Mpumalanga (whenever has money to go home) | |

| 15 | In a park in Plein St | Germiston (every month) | |

| 16 | On the street outside the depot in Bryanston | Carltonville (every weekend) | Lesotho |

| 17 | Unoccupied house in Brixton | Nkandla, KZN (once a year, usually December when it rains) | |

| 18 | Flat in JHB CBD | Lesotho (every 2 months) | |

| 19 | Homeless shelter in Kerk Street in town | Mabopane, Pretoria (never goes home by choice) | |

| 20 | Under the bridge in Newtown | RDP house in Evaton West (every weekend) | |

| 21 | Under the bridge in Newton | RDP house in Evaton West (every weekend) |

These regular street sleepers have different motivations and housing needs from the city’s ‘destitute homeless’. Indeed some are property owners in their own right.

Recyclers choose to spend work nights in Johannesburg to save on transport costs; and to be ready to start their outbound journeys to suburbs very early in the mornings. They choose spacious places where their accommodation may be cramped but they are able to store their goods. Recycling work involves gathering and then later, sorting the load prior to having it weighed at the depot. Recyclers need space for separating and sorting bulky items and they need time to do this sorting. They also need place to stockpile items until they have amassed enough of a particular material to make exchange at the depot worthwhile.

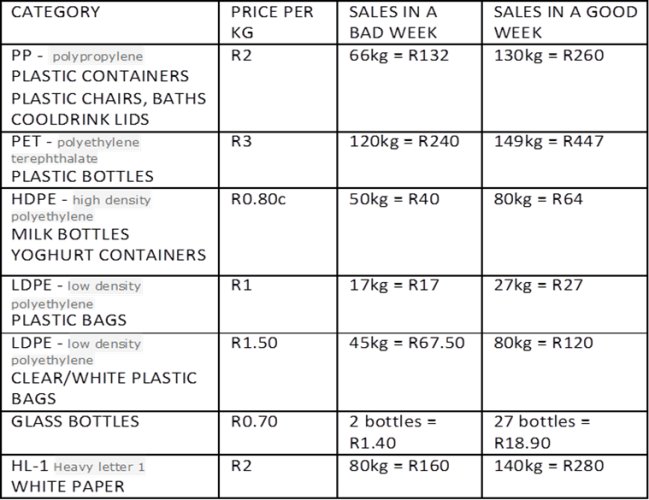

The business of informal recycling depends on the prices paid by buy-back centres for particular categories of waste. Recyclers typically accumulate stock over the week, and on Friday afternoons and Saturday mornings they sort the stock and take it to whichever accessible recycling station offers the highest price per category.

These were typical prices in 2010:

Table 3: Typical prices for resaleable waste in Johannesburg in 20102

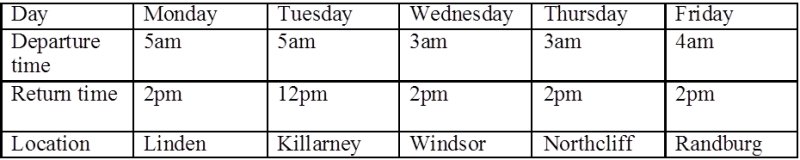

Paul Motshweneng and his partner have both worked as recyclers since they came to Johannesburg from Lesotho in 2005. They live with their baby in a makeshift room, 2m X 2m, in an illegally occupied warehouse in Doornfontein. It is a building with no formal water or electricity services. From here Paul conducts his daily routes to the destinations (suburbs of Johannesburg) outlined in Table 4. He says the competition has increased and so he has to wake earlier and earlier to be first at the bins he works every week.

Table 4: Daily schedule of a recycler3:

2Amounts estimated by recycler Paul Motshweneng, interviewed by Tanya Zack, 2010

3As described by recycler Paul Motshweneng, interviewed by Tanya Zack, 2010

Paul’s Wednesday route is a return journey of some 34kms. On the way back he is pulling more than his body weight in waste and in wet weather it is a much heavier load.

Chaturvedi, B (2009) A scrap of decency. New York Times, August 4. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/05/opinion/05chaturvedi.html

Gutbertlet, J; Tremblay, C; Taylor, E; Divakarannair, N (2009) Who are our informal recyclers? An inquiry to uncover crisis and potential in Victoria, Canada. Local Environment 14: 8 733-747

Da Silva, M; Fassa, A; Siqueira, C (2005) World at work: Brazilian ragpickers. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 62 (10) 736-740

Opportunity

A cursory survey of South African Township suggests that these are rapidly changing places not only in size and character but with emerging new opportunities despite the odds. Unlike the image of bed-room communities of the past, some of these townships are beginning to express themselves as significant bastions of culture, development and growth. These changes are bound to impact on their relationship to the “formal City” as we know it. The prospects for advancement are therefore real.

The demand for access to new products and services is going to require innovative response from both public and private sector. Finding strategies to retain spending power and promotion of local business opportunities is central to this open dialogue at the informal city exhibition.

The demand for improved access to transport networks, telecommunication, and basic services such as energy, water and electricity will require new innovations innovative responses from the public sector. Some of the opportunities cited for private sector range from financial services, home upgrading and repairs and a range of lifestyle services.

Panel members will be requested to assist in exploring these emerging opportunities and possible constraints. The following questions are proposed to trigger and guide the debate:

- What are the characteristics of current township economic activities?

- What are possible opportunities going forward?

- What are the current challenges to these opportunities?

- What recommendations can be made to both public and private sector?

- How can these be best communicated?

Facilitator:

- Nellie Lester, SA Cities Network

Speakers:

- The Informal/Formal Interface of Investment in Township Areas

Rob McGaffin, Urban Landmark - Slovo Park: the Innovation of an Economic Urbanism

Michael Hart, Michael Hart Architects & Urban Designers - The Peoples' Economy

Edmund Elias, South African National Traders' Retail Alliance

Slovo Park: the Innovation of an Economic Urbanism

Michael Hart, Michael Hart Architects & Urban Designers

1. Contextualising Urban Design practice

Overcoming human problems is the element common to all Urban Design approaches. Urban design puts people first.

For those from disenfranchised communities in South African cities, the difficulty is facing the many formal urban policies that don’t offer alternatives. The question is, how can people make a living on the fringes of formality without falling into contravention of urban laws, and walking into the web of exploitation by landlords and letting agents?

As Urban Design practitioners, it may be our role to offer an enabling framework that acknowledges the linkages between the formal economy and the informal economy. And, given that there are linkages between economies, there is a need for a more equitable relationship. It is interesting that there is a move from governments and employers to convert formal jobs to informal jobs – rather than the other way around (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs USA www.un.org/desa/).

The relationship between formality and informality is symbiotic and often co-dependant. An example of this would be an informal street trader located in front of a store selling the goods for the store owner; or informal cooked food traders given pavement space in return for buying goods from the formal shops along the street. This relationship offers an alternative view in terms of zoning, land-use, and the kind of alternative services required.

The management of informal operators within the public transportation sector, the trading and manufacturing sector and the informal housing sector requires a different way of thinking about a supportive structure that allows for informality to operate within the realms of safety, hygiene, mutual respect for people, buildings and environment, and access to services and facilities.

2. Proposing a Hypothesis that Urban Design can offer an enabling framework for the creation of an economic urbanism.

Urban Design criteria for human development are universal in principle, outlining that development should be guided by wholesome attitudes towards spatial integration, connectivity, social and cultural inclusions, public space, “place making”, and long term social, economic and environmental sustainability.

In SA, housing projects are typically defined by their quantitative outcomes and political objectives, often resulting in anti-social environments. The short term delivery of housing should be transformed into long term neighbourhood developments with integrated enabling frameworks that allow for economic and socially integrated environments.

Urban design places the Public realm as one element that operates as a structuring principle. The ‘Capital Web’ (David Crane ‘The City Symbolic’ 1960) theory spoke of a network of linkages between major city installations and resulted in cities requiring advanced high speed transit and high capital input.

I am proposing an ‘Innovation Web’, a network that is organic and that can be developed by people on the ground. It is a bottom-up structure that allows innovation from individuals to contribute in a meaningful way. The Innovation Web delivers an infrastructure that supports social and community facilities, public space, trading and manufacturing facilities, service infrastructure that enables informal and formal economic activities; and it creates an environment that offers pride of place to its inhabitants.

Economic development and ecological urbanism are symbiotic. The ‘Innovation Web’ proposes walkability, densification and efficient land use, inclusion of social and cultural facilities, and the ability for local residents to support local business in the trading of goods and services, manufacture and urban agriculture. Under this model, infrastructure costs reduce as it is more efficient to service nodal developments versus servicing development sprawl. An example of this is a single family that runs a business from home thus reducing the duplication of service costs and the overall ecological footprint of growing cities.

Similarly, non-motorised transport and the increased use of public transport for longer distances will reduce the building of high specification roads and reduce CO2 emissions. And placing an emphasis on innovation and empowering inhabitants to create their own employment will reduce the drain on the state by lowering social grants and improving human capital.

The Slovo Park project was seen as a case study for proposing ideas that deliver 2000 housing units into a neighbourhood development that integrates the concept of the ‘Innovation Web’.

Previous layout plans depicted a loose arrangement of a typical housing block repeated and placed in an unstructured manner, with internal roadways and vast parking lots. This was turned down by the City of Johannesburg planning department, which created an opportunity for an alternative approach.

The starting point was acknowledging the site’s contextual relationships and broader urban design frameworks that identified Slovo Park as an element within a larger corridor. It was evident that the project is an opportunity to connect neighbouring suburbs. Numerous linkages would encourage urban integration and the development of a high street allowing greater mobility, choice and mixed use functions.

This connectivity became the core to proposing a public realm network consisting of a pedestrianised activity spine that links the high order transportation network and its related commercial core with the community core of public spaces, community and religious buildings.

The activity spine offers informal and formal trading facilities, defined public space, landscaping, public seating and shade structures. The idea is that the pedestrian spine is a convenient linking device and will be well frequented by residents and visitors creating a desirable environment for business to flourish.

The vision of an economic urbanism is to implement an enabling environment that attracts future growth.

3. Resilience (inspired by Resilientcity.org)

The definition of Resilience: A reservoir of renewable resources and the ability to cope with adversity which includes creative problem solving and the ability to adapt to change.

Urban design principles for resilience reinforce the logic of neighbourhood design :

- Density, Diversity and Mixed-use

- Prioritise walking and non motorised travel

- Supportive efficient public transportation

- Place Making

- Complete Communities and Complete Streets

- Integrate natural systems and manage climatic responses

- Integrate technical and industrial systems with environmental concerns of complementary energy disposal and bi-product recycling

- Community engagement

- Design for emergency services and long term maintenance

- Prioritize infill development within existing serviced nodes reducing the need to increase the urban footprint

Conclusion

The role of the built environment professional must contribute to the flexibility of the regulatory framework that determines use. Zoning and town planning schemes should offer more flexibility. The adaptive re-use of land and buildings and the sharing of facilities for different uses must be encouraged. We need the supportive systems of a clean, healthy and safe environment with an emphasis on the human quality that will ensure liveability and opportunity.

The Informal/Formal Interface of Investment in Township Areas

Rob McGaffin (research courtesy of Urban Landmark)

In this presentation, the three following examples will be used to explore the informal/formal interface of investment in the township areas:

- Roll-out of retail centres in the township areas

- Roll-out of transport infrastructure in township areas

- Household investment in township areas

RETAIL CENTRES

Relative Scale of Development – Amount of formal shopping centre space developed in township and rural areas relative to the total.

…..Mixed Reactions to ‘mall’ developments:

Pan Africa Mall in Alexandra:

‘Spokesperson of the Greater Alexandra Chamber of Commerce and Industry’s youth wing, John Makgoka, said the body would embark on a protest this week to discourage consumers from shopping at the mall until it was “fully owned” by locals. “The people of Alexandra will fight for what belongs to them. We will cripple the tenants until they leave.” (Soweton, 15 June 2009)

Tebogo Mogashoa of Pan Africa Development Company says, “Pan Africa Shopping Centre represents the dreams and aspirations of the Alexandra people. We developed it for them.” (Eprop, 18 August 2009)

Impact of Centres

The study ‘Taking Stock: the development of retail centres in emerging economy areas’, conducted by Urban LandMark1 in 2011, examined 6 centres to better understand the impact of this type of development on local consumers, local businesses and the local economy. The results of the survey showed:

1Demacon Market Studies (2010) The impact of the development of formal retail centres in 'emerging economy' areas in South Africa

1.0 Impact on Consumers:

1.1. Impact of shopping patterns:

- Decrease in external shopping from 55% to 38%

- 71% of formal shopping done at new centre

- 31% said they shopped less frequently outside the area

- 66% said that local expenditure had increased

- Shopping at local businesses dropped from about 23% to 20%

1.2. Impact on time and travel costs:

- Travel time to formal centres dropped by 57%

- Travel time to small businesses dropped by 25%

- Travel costs to formal centres dropped by 36%

- Travel costs to small businesses dropped by 21%

2.0 Impact on Small Businesses:

2.1. Impact of centre in terms of location:

- Safety & security – 54% (same), 32% (incr)

- Visibility – 39% (same), 41% (incr)

- Transport interchanges – 36% (same), 51% (incr)

- Banking – 50% (same), 41% (incr)

- Foot-traffic – 30% (same), 48% (incr)

2.2. Impact on business performance

- 75% saw growth of 5-10%, 25% saw a decline of 5-10%

- Employment – 64% (same), 14% (incr)

- Profit – 40% (same), 31% (incr)

- Turn-over – 42% (same), 29% (incr)

- Supply - 13% of stock bought from the centre

2.3. Factors stopping the relocation to the centre:

- Lack of customers

- Lack of funding

- High rentals

- Low profits

- Competition from nationals

....50/50 split between those businesses wanting to (and not) relocate to the centre2008 research of retail development in Soweto by Professor Andre Lighthelm, Research Director of the Bureau of Market Research at UNISA, similarly found that that the impact of shopping mall development on existing small businesses could not be explained uni-dimensionally, purely portraying a decline in small business activity.

“While some small businesses expect to close their doors, several small businesses were established due to mall development. This is particularly true of street vendors with their ability to intercept large numbers of township consumers at the new malls.”

“A third of the respondents surveyed in Soweto predict an expansion of their business turnover, while another third expects a contraction. Some regard the newly developed malls as their main competitor, while others experience stiff competition from fellow small businesses.”

(Small business sustainability on a changed trade environment: the Soweto case, 2009)Opportunities & Challenges

One of the main challenges is to manage the relationship between the formal and informal activities such that a positive interface between the two is created. If this is done, opportunities exist for formal retail to act as a magnet to create a larger customer base for the smaller interprises, which can enhance their growth and viability. By increasing the customer base, turn-overs and gross profits of the smaller businesses can be increased, which in turn enables some of them (where appropriate) to pay market rentals for, albeit smaller, formal spaces (e.g. Johannesburg CBD traders).

In addition, a positive informal/formal retail development in a township area can create an obvious focal point for investment and therefore act as a strong catalyst for nodal development. The creation of such focal points are important considering that many of these township areas were developed as dormitory towns and often lacked an economic logic with respect to locations that lent themselves to viable investment.

INFRASTRUCTURE

Context

Infrastructure similarly has the potential to set up an economic logic in a township, and a location for investment in areas previously designed as dormitories.

However, the large infrastructure roll-out programme is occuring in a context of:

- Increasing pressure on finances across the different spheres of government

- Increasing pressure to increase inclusionary development, especially housing

The challenge is how one facilitates access by the poor to the well located sites generated by the infrastructure i.e. how do we increase the bidding power of the poor for these key sites?

The question therefore is whether the provision of transport infrastructure can generate sufficient additional (incremental) value to either:

- Fund or partially fund the infrastructure over a reasonable pay-back period

or - Generate enough surplus returns such that inclusionary development can be incorporated into a project without reducing the rates of return required to induce the investment in the first place.

3 case studies

In order to answer this, Urban LandMark commissioned a study on the impact of transport infrastructure on property values1. The study looked at three case-studies consisting of different types of transport infrastructure, namely a BRT station (Mooki Street, Soweto), a major road interchange (PWV9 near Diepsloot) and a metrorail station (Khayelitsha, Cape Town). The aim of the study was to assess the degree to which such infrastructure impacts upon property values and the possible mechanisms that could be used to capture any increased value that could be used to cross-subsidise the poor or pay for the infrastructure itself.

Using a number of residual and comparative methods, the study found that assuming the development conditions were in place, the infrastructure could generate surplus property values. The study suggests that this value increase will differ by the different types of transport infrastructure but due to the limited number of case-studies, this would need to be verified with further research.

2 ADEC (2011)Value Capture from Transit –orientated development and other transport interchanges.

Value Capture Mechanisms

“Value-capture” is a term used to describe the process of extracting (in different ways) the additional value that accrues to a property as a result of some public investment such as the provision of public transport or a school. It is the extraction of the value over and above the value that the property would have if the public investment had not taken place. It is usually argued that as the additional value was created as a result of the state’s actions and not the owner, it is justifiable for the state to lay claim to this value through various mechanisms for some public purpose such as paying for public transport.

Drawing on local and international evidence, the Urban LandMark study identified a number of mechanisms as potential ways to capture some or all of the increased value that occurs as a result of the provision of tranport infrastructure. There are two broad categories of value-capture mechanisms, although the distinguishing line can be blurred from time to time and some mechanisms can exhibit qualities from both categories.

The first category includes those mechanisms that try to use the increased value to bring about, or facilitate, a broader planning outcome (“use or social/spatial restructuring outcome”) such as densification and inclusionary housing. The second category includes those mechanisms that extract income in the guise of a tax or a tariff from the increment value to finance the infrastructure or some other development (“income or cost recovery outcome”). Examples of value capture mechanisms include:

Use Mechanisms:

- Land Banking

- Zoning Tools

- Air Rights

- Business Improvement District

Income Mechanisms:

- Development Contributions

- Land Value Increment Taxes

- Land Increment Financing

Opportunities & Challenges

Value Capture can offer many opportunities such as increasing the revenue collection by municipalities and allowing greater flexibility in local expenditure. It can also create the potential for cross-subsidisation for developmental purposes to occur and the improved infrastructure provision can improve the access of the poor to the City. This provision includes not only the roads and railway lines but also the the quantity and quality of the rolling stock that runs on these roads and lines. The quote below highlights the daily challenges of the poor in trying to access the work and other opportunities offered in a city.

“A concerned city woman has told of how she witnessed a mother being forced from an overcrowded train and separated from her child.

On Monday, while waiting at Bellville station for her regular 5.50pm train to Strand, Gloria Solomons, 60, was horrified when she saw the woman forced out of a packed carriage.