You are here

Learning From Our Own Backyard

LEARNING FROM OUR OWN BACKYARD

Informal provision of affordable rental stock

Research conducted into backyard rental since 2002 for amongst others the GDoH and the NDoH

Lone Poulsen and Melinda Silverman

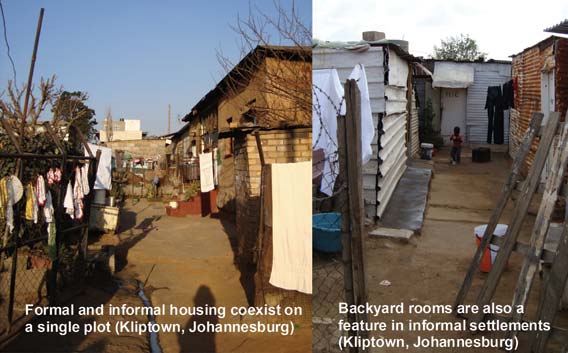

At the back of almost every formal house in South Africa is an additional building. This might be a servant's quarter, a granny flat, 'a room for rent', an informal shop, a spaza or a hairdressing salon . In many instances these backyard rooms have been informally developed built by the owners of the formal house in an attempt to derive income from their properties. Backyard rooms are a notable feature of the South African urban landscape and have a long history in South African cities:

Over a hundred years residents of Alexandra built clusters of rental rooms on their large peri-urban plots. This gave rise to the "Alex yard" which remains the primary social entity in Alexandra. In the townships developed by Apartheid government in the 1950s, residents gradually added backyard rooms in spite of state efforts to curb African urbanisation. New rooms were often disguised as "a garage and two stores" when such additions were illegal.

Today the pattern of building backyard rooms remains popular. Beneficiaries of the RDP housing programme rolled out by the post-Apartheid state have also been adding rooms at the backs of their plots. During the 1990s more new tenancies were created in the informal than the formal sector, most often in the form of backyard rooms. The 2001 census counted 460 000 households, or about 2.3 million people, living in backyard rooms. Until recently "backyard shacks" have been viewed in a negative light by the authorities - largely because the increase in density has placed significant strain on existing infrastructural services.

Although the quality of backyard rooms is often poor, this form of accommodation - built entirely without government help - offers potential solutions to a number of South African housing problems.

1. The addition of backyard rooms helps to increase housing density, which means that urban land is used more efficiently. The same amount of road space and the same length of pipe runs can be used to serve additional households. Increased urban densities also generate higher thresholds for public transport, retail and social services making these amenities more viable. Additional rooms on the plot often help to define better outdoor space, creating courtyards where children can play and residents can socialise.

2. The addition of backyard rooms allows the owner of the primary dwelling to derive income from his/her property in the form of rental rooms or home enterprises. This means that a house provides more than shelter and also functions as an economic generator. This increases the asset value of the property.

3. The addition of backyard rooms provides accommodation that is more responsive to diverse household arrangements where families are rarely nuclear - mom, pop and 2.5 kids - but more likely to comprise grannies looking after AIDs orphans, extended families , women headed households, and multiple households.

4. The addition of backyard rooms improves the supply of much-needed affordable rental accommodation, fulfilling the needs of an estimated 80% of the population who cannot afford formal rental housing. Cheap rental options are necessary in the context ongoing migrancy where work in cities, but maintain links with families elsewhere and in the context of increasing labour mobility where urban residents are forced to move in search of jobs.

5. From a municipal perspective backyard rooms are a far less alarming manifestation of informality than freestanding shacks which are often erected on inappropriate or unsafe land. Backyard rooms are built on land that has already been zoned as residential.

It is for these reasons that backyard rooms are increasing being seen as a solution to South Africa's housing shortage rather than a problem.

Continued on Panel 2

.

LONE POULSEN: ACG ARCHITECTS & DEVELOPMENT PLANNERS

MELINDA SILVERMAN: DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE: UJ

Powered by AA Media and The Architects Collective of South Africa