BACKYARD / OWNER INTERVENTIONS

Below is a brief excerpt from each of the projects in this category. Click on the links or image to see the full project panel details and illustrations.

Flats of Du Noon

Exhibitor: H. Wolff

Over the past decade, a new type of privately developed, rentable housing started emerging in Du Noon, Cape Town. As an economic model it is similar to the renting of backyard shacks, but the rentals are three times higher on average. The extraordinary income-generating potential of the flats in Du Noon and their morphological innovation is what sparked interest in this study.

Learning from our own backyard

Exhibitor: Lone Poulsen and Melinda Silverman

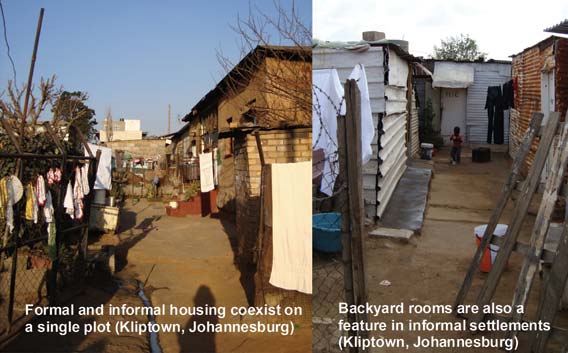

At the back of almost every formal house in South Africa is an additional building. This might be a servant's quarter, a granny flat, 'a room for rent', an informal shop, a spaza or a hairdressing salon . In many instances these backyard rooms have been informally developed built by the owners of the formal house in an attempt to derive income from their properties. Backyard rooms are a notable feature of the South African urban landscape and have a long history in South African cities

Flats of Du Noon

FLATS OF DU NOON

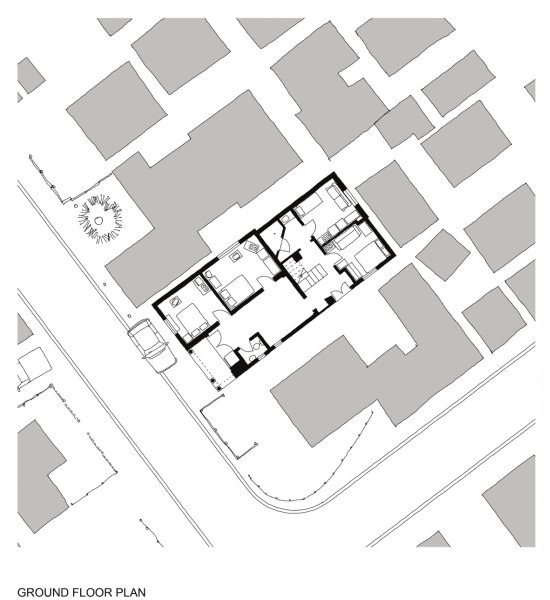

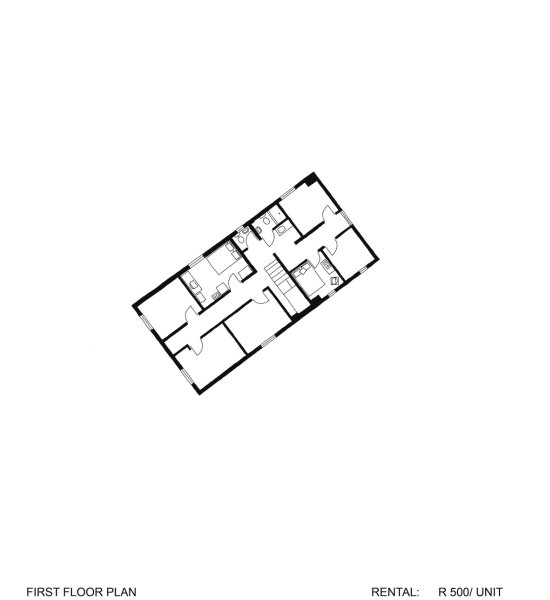

A study of owner developed rentable housing

Du Noon, Cape Town 2010

Privately initiated and funded research by H. Wolff

Assisted by V. Loseby, M. Willemse, A. van Wyk and E. Gericke

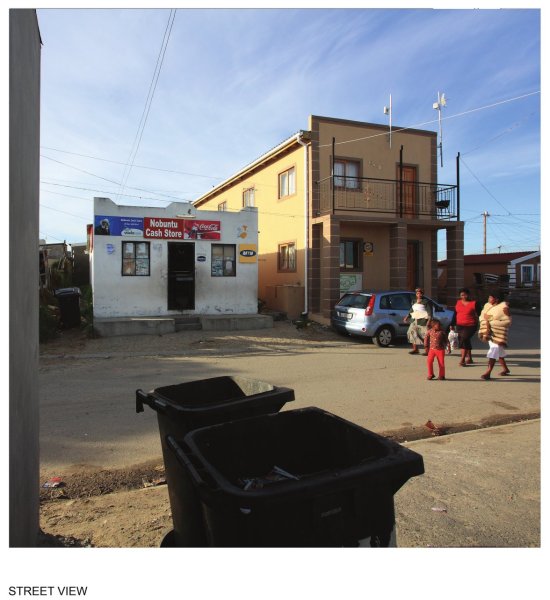

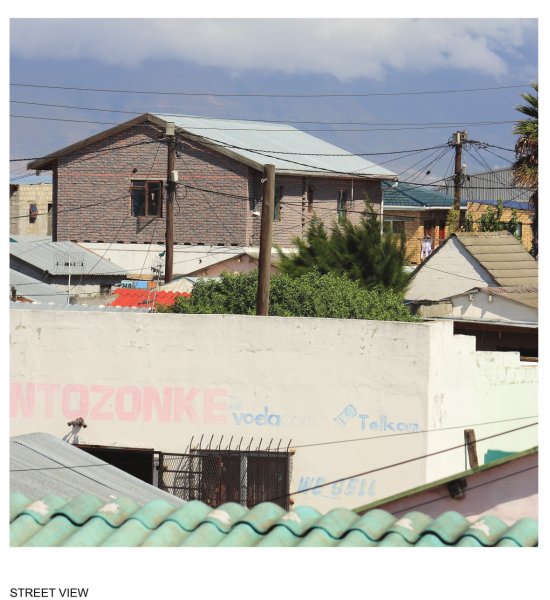

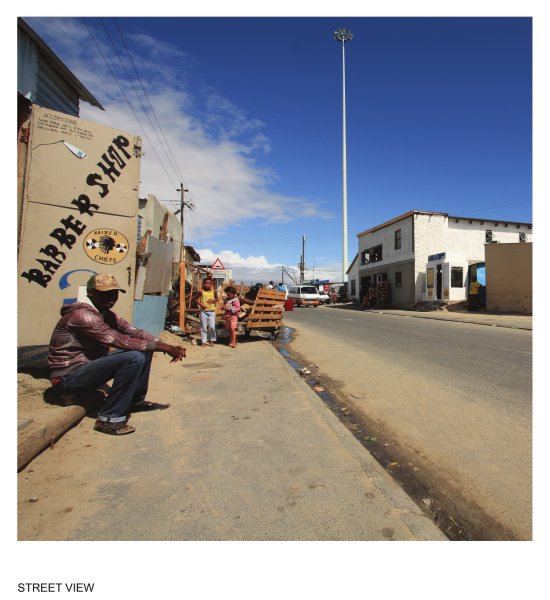

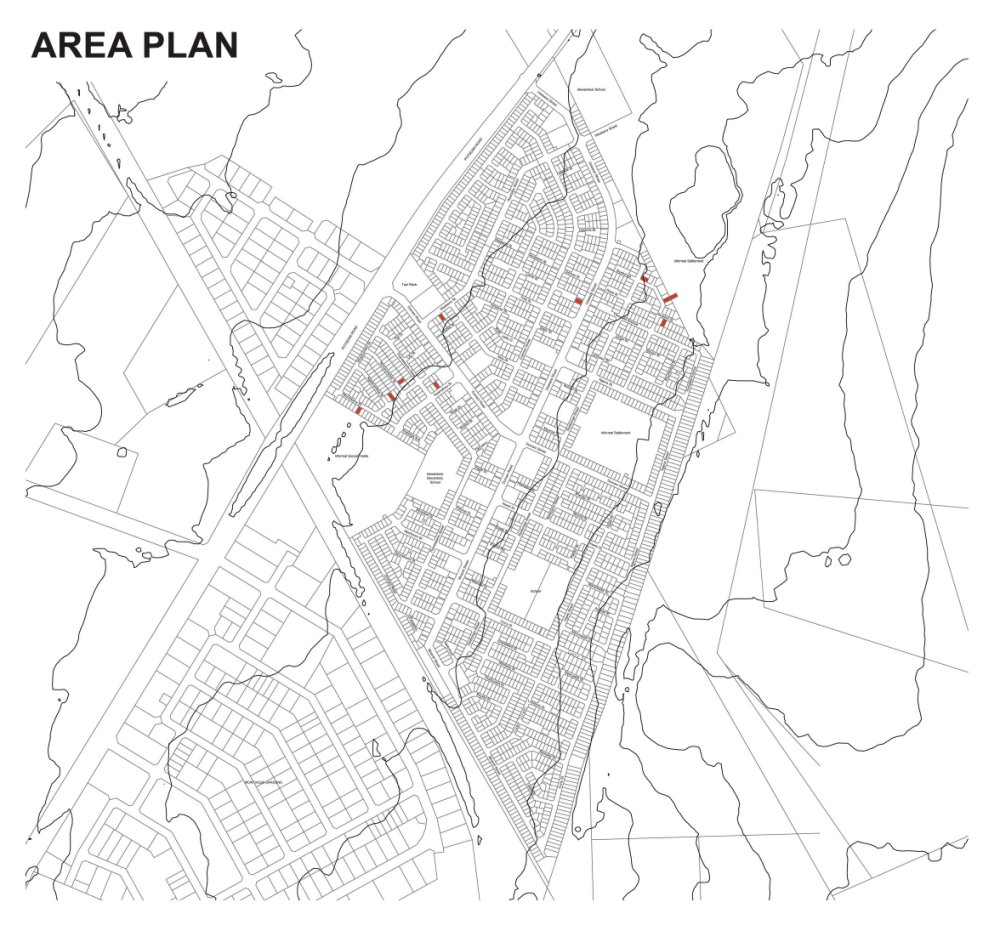

Over the past decade, a new type of privately developed, rentable housing started emerging in Du Noon, Cape Town. As an economic model it is similar to the renting of backyard shacks, but the rentals are three times higher on average. The extraordinary income-generating potential of the flats in Du Noon and their morphological innovation is what sparked interest in this study.

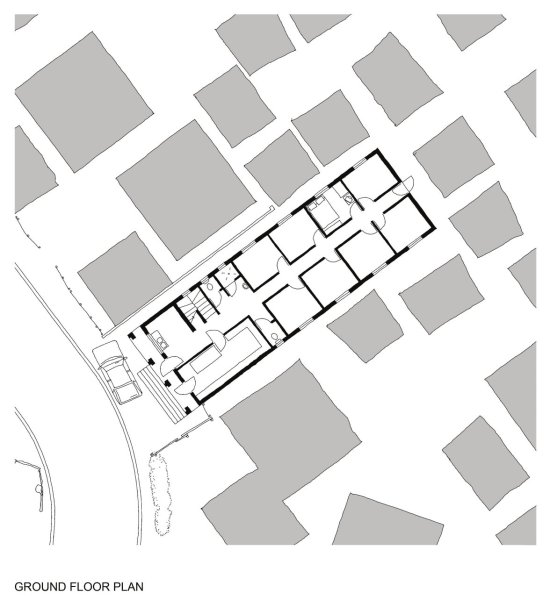

Du Noon is a Post-Apartheid settlement that owes its origins to a Provincial Governmental housing roll-out that started in 1996. Typically a 38m' RDP house would be built in the centre of a 115m' property. As an area for social housing, Du Noon is uncharacteristically well located near industrial, manufacturing, agricultural and residential job opportunities. The intensity of economic opportunity has resulted in rapid informal densification of Du Noon and the possibility to develop more permanently constructed, rentable apartments.

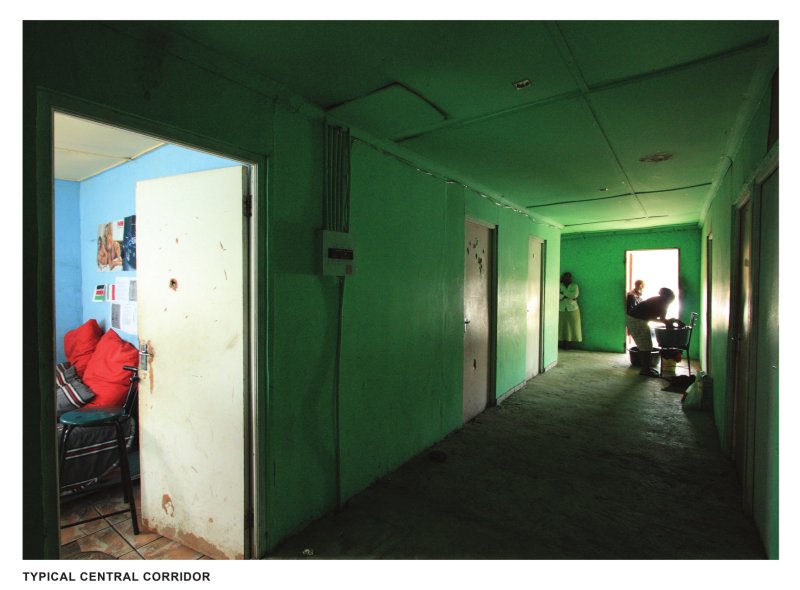

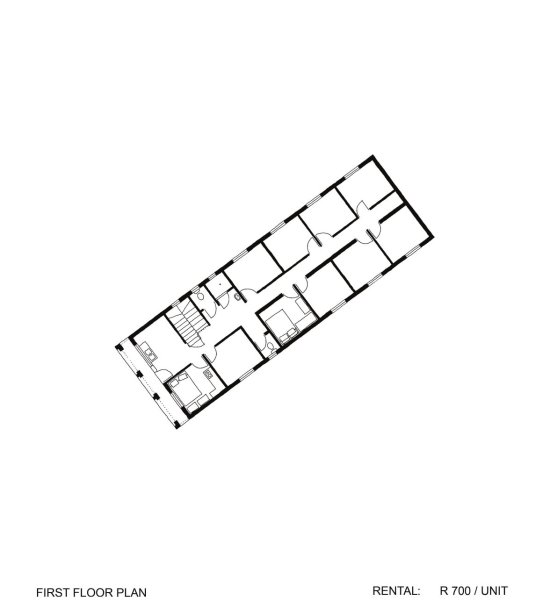

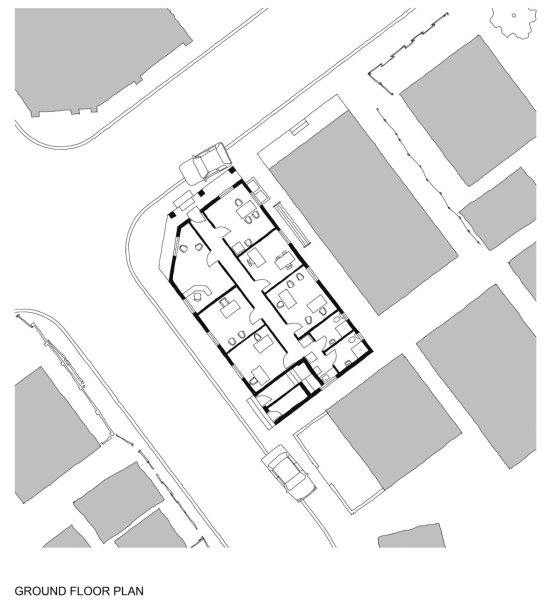

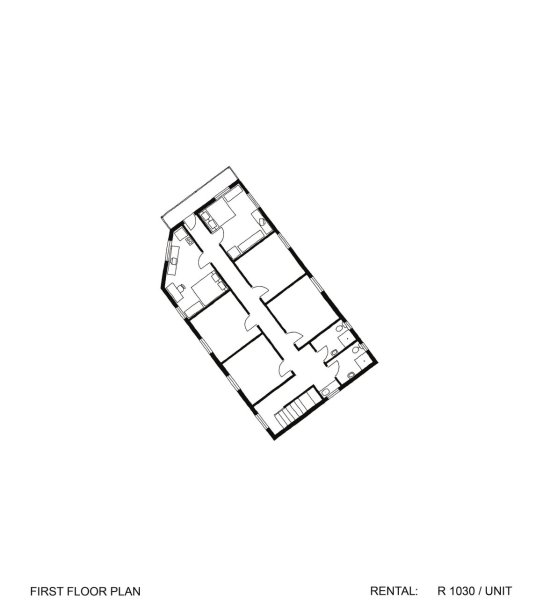

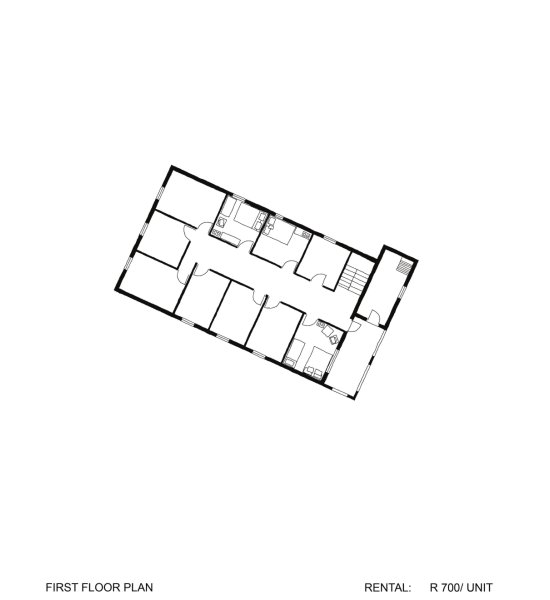

The Du Noon flats have developed a typical morphology that consists of a series of single room flats off a central corridor with shared ablutions. The flat sizes range between 6 and 13m2, with an average flat size of 8m'. The rentals for these flats range between R 400 - R 1030 per flat, with all flats being occupied in reasonably similar ways. Because of the consistent flat sizes, the content of each flat is typically a double bed, cupboard, couch or chairs, television , microwave, two plate stove and sometimes a fridge . The flats are occupied by between 1 and 4 people.

The development of these flats was financed in a variety of ways , but never with a bank loan. Some were financed with profits from vegetable or alcohol trade and others through stokvels. A common method of financing was to develop incrementaliy- completed flats were rented out while the remainder were still under construction.

All of the buildings in the study were constructed from masonry, with roofs made of timber beams and covered with roof sheeting. The internal floors were either timber beams and plywood boards or various forms of concrete floors. In general the buildings were built fairly well however, there are some violations of the National Building Regulations, most notably the fire regulations. The most common problems being a lack of a second means of escape and non-conformity with the stair designs. Most of these problems could have been overcome if the owners had access to professional advice.

Du Noon is zoned as 'Informal Residential'. This zoning has facilitated the development of rentable housing, due to it placing unlimited restrictions on the number of units per erf, provided that the primary use is for residential purposes. Many of the flat buildings have a shop on ground floor, one building even provides rentable office space. The mix of functions in these buildings, and the extreme density of flats per erf, has resulted in buildings that push right up to the road edge and therefore participates in the spatial definition of the street.

Due to Reception Area’s complex and dense urban fabric, the strategy is realized in three scales: an existing toilet upgrade, a medium-sized toilet and shower facility, and a large service centre with toilets, comfortable bathrooms, laundry and community services.

The large units are arranged around semi-private courtyards. Besides regular bathrooms, they contain retail spaces which could be used by a hairdresser, internet cafe, laundry, tuck-shop, crèche, gym, etc. The two roof terraces can be used for drying clothes and by the gym as outdoor exercising spaces respectively.

Through incorporating lessons learnt from the dynamic urban and architectural character of the Reception Area, the facilities are cross-programmed to offer multiple services and income streams. All typologies would provide business opportunities for local caretakers and operators.

Continued on Panel 2.

HEINRICH WOLFF

Flats of Du Noon (Panel 2)

FLAT DATA

| Average unit size: | 8m2 | ||

| Typical rental: | R 700 / month | ||

| R 50 - R100 / m2 | |||

| R 45 - R 80 / m2 | (including ablutions) | ||

| Comparative rentals: | R 700 ÷ 8m2 | = R 88 / m2 | DU NOON |

| R 3500 ÷ 40m2 | = R 88 / m2 | CAPE TOWN CITY | |

| R 3000 ÷ 40m2 | = R 75 / m2 | BANTRYBAY | |

| R 3500 ÷ 40m2 | = R 88 / m2 | BANTRY BAY (upmarket) | |

| R 2850 ÷ 40m2 | = R 71 / m2 | BLOUBERG | |

| R 2650 ÷ 40m2 | = R 66 / m2 | DURBANVILLE |

Back to Panel 1.

HEINRICH WOLFF

Learning From Our Own Backyard

LEARNING FROM OUR OWN BACKYARD

Informal provision of affordable rental stock

Research conducted into backyard rental since 2002 for amongst others the GDoH and the NDoH

Lone Poulsen and Melinda Silverman

At the back of almost every formal house in South Africa is an additional building. This might be a servant's quarter, a granny flat, 'a room for rent', an informal shop, a spaza or a hairdressing salon . In many instances these backyard rooms have been informally developed built by the owners of the formal house in an attempt to derive income from their properties. Backyard rooms are a notable feature of the South African urban landscape and have a long history in South African cities:

Over a hundred years residents of Alexandra built clusters of rental rooms on their large peri-urban plots. This gave rise to the "Alex yard" which remains the primary social entity in Alexandra. In the townships developed by Apartheid government in the 1950s, residents gradually added backyard rooms in spite of state efforts to curb African urbanisation. New rooms were often disguised as "a garage and two stores" when such additions were illegal.

Today the pattern of building backyard rooms remains popular. Beneficiaries of the RDP housing programme rolled out by the post-Apartheid state have also been adding rooms at the backs of their plots. During the 1990s more new tenancies were created in the informal than the formal sector, most often in the form of backyard rooms. The 2001 census counted 460 000 households, or about 2.3 million people, living in backyard rooms. Until recently "backyard shacks" have been viewed in a negative light by the authorities - largely because the increase in density has placed significant strain on existing infrastructural services.

Although the quality of backyard rooms is often poor, this form of accommodation - built entirely without government help - offers potential solutions to a number of South African housing problems.

1. The addition of backyard rooms helps to increase housing density, which means that urban land is used more efficiently. The same amount of road space and the same length of pipe runs can be used to serve additional households. Increased urban densities also generate higher thresholds for public transport, retail and social services making these amenities more viable. Additional rooms on the plot often help to define better outdoor space, creating courtyards where children can play and residents can socialise.

2. The addition of backyard rooms allows the owner of the primary dwelling to derive income from his/her property in the form of rental rooms or home enterprises. This means that a house provides more than shelter and also functions as an economic generator. This increases the asset value of the property.

3. The addition of backyard rooms provides accommodation that is more responsive to diverse household arrangements where families are rarely nuclear - mom, pop and 2.5 kids - but more likely to comprise grannies looking after AIDs orphans, extended families , women headed households, and multiple households.

4. The addition of backyard rooms improves the supply of much-needed affordable rental accommodation, fulfilling the needs of an estimated 80% of the population who cannot afford formal rental housing. Cheap rental options are necessary in the context ongoing migrancy where work in cities, but maintain links with families elsewhere and in the context of increasing labour mobility where urban residents are forced to move in search of jobs.

5. From a municipal perspective backyard rooms are a far less alarming manifestation of informality than freestanding shacks which are often erected on inappropriate or unsafe land. Backyard rooms are built on land that has already been zoned as residential.

It is for these reasons that backyard rooms are increasing being seen as a solution to South Africa's housing shortage rather than a problem.

Continued on Panel 2

.

LONE POULSEN: ACG ARCHITECTS & DEVELOPMENT PLANNERS

MELINDA SILVERMAN: DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE: UJ

Learning From Our Own Backyard (Panel 2)

LEARNING FROM OUR OWN BACKYARD

New models of affordable housing

Research conducted into backyard rental since 2002 for amongst others the GDoH and the NDoH

Lone Poulsen and Melinda Silverman

The backyard room is receiving increasing attention from South African policy makers and design professionals as a potential solution to some of South Africa's most pressing housing problems - excessively low densities, a shortage of affordable rental housing, housing units designed only for nuclear families.

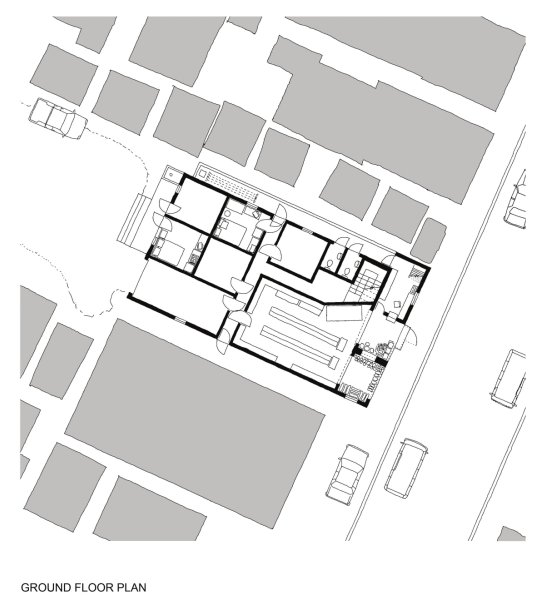

Informed by these theories and observations of organically developed backyard rooms, architects and urban designers have started to develop housing models that anticipate and make provision for backyard additions. These new housing prototypes harness the advantages of backyard accommodation while seeking to mitigate the disadvantages associated with unplanned, unanticipated densification.

These new models are characterised by:

Reduced plot sizes. This ensures that urban land - an increasingly scarce resource - is used more efficiently.

Narrow street frontages. This reduces the amount of road space and pipe runs needed to serve individual plots. This results in significant savings in both the capital and operating costs of services.

Unorthodox siting of the starter unit. Rather than locating the house in the middle of the plot, as per conventional suburban housing, the starter unit is located near the front of the site and along one of the side boundaries. This immediately creates an identifiable street edge, allows for street-related commercial activities like

spazas, maximises the amount of useable outdoor space, and ensures that adequate space is available at the back of the site for the incremental addition of backyard rooms.

Building the starter unit as a double storey. This ensures that the building footprint is reduced maximising the amount of outdoor space.

The advantages of these new housing models are manifold:

They increase densities and therefore make more effective use of infrastructure;

They can be developed incrementally as the primary homeowner acquires more capital;

They harness the entrepreneurial talents of the community and provide jobs for small contractors;

They disperse political risk amongst a large number of small landlords;

They accommodate a wide variety of living arrangements on the same plot - multiple households, home-based enterprises, a mix of freehold and rental tenure.

These principles have already been realised in a number of exemplary projects across the country:

In the PELIP project in Nelson Mandela Bay, Noero Wolff developed a row house typology with two and three storey units. Each unit was conceptualised as a starter house, designed to allow beneficiaries to customise their housing in accordance with their own requirements. Units are narrow and built right up against the street edge, allowing for flexible space in the back yard to accommodate additions or rentable rooms.

In the Far East Bank project in Alexandra, in Johannesburg, ASA Architects developed clusters of six to eight units with a mix of double storey main houses and single storey rental rooms. Some beneficiaries are renting out the rooms to tenants and some are using the rooms to operate small businesses. The road space within each cluster functions as a contained courtyard proViding a safe space for children to play.

In the 10x10 project in Freedom Park, a suburb in Cape Town, MMNLuyanda Mpahlwa architects developed two-story timber frame and sandbag infill row houses, designed and built with community involvement. The houses are placed close to one another on the street edge, immediately contributing to a sense of urbanity.

In Lufhereng, in Mogale City, 26°10 South and Peter Rich Architects created row-houses comprising single and double-storey units which afford a sense a variety. The houses are built close to the street edge with private gardens at the back. The use of smaller-than-usual stands has helped increase residential densities and some residents have already converted rooms into tuck-shops and hairdressing salons.

Back to Panel 1.

LONE POULSEN: ACG ARCHITECTS & DEVELOPMENT PLANNERS

MELINDA SILVERMAN: DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE: UJ