THE SA INFORMAL CITY ONLINE EXHIBITION

UN-BUILT PROJECTS: RESEARCH AND REFLECTIONS

- Diepsloot – Housing & The Informal City

Exhibitor: 26’10 South Architects and Lone Poulsen - Diepsloot - Soak & Curl

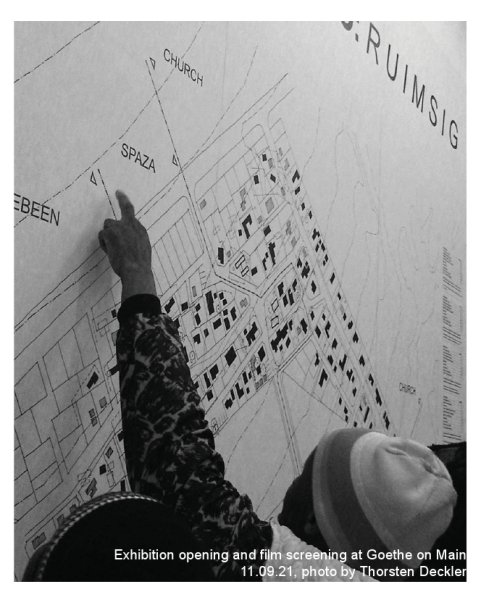

Exhibitor: 26’10 South Architects - Informal Studio - Ruimsig

Exhibitor: 26’10 South Architects - Sans Souci Cinema

Exhibitor: 26’10 South Architects, Lindsay Bremner - Subsidised Housing Assets

Exhibitor: FinMark Trust

BACKYARD / OWNER INTERVENTIONS

- Flats of Du Noon

Exhibitor: Heinrich Wolff - Learning from our own backyard?

Exhibitor: Lone Poulsen and Melinda Silverman

INNER CITY INFORMALITY

- Brook Street Market

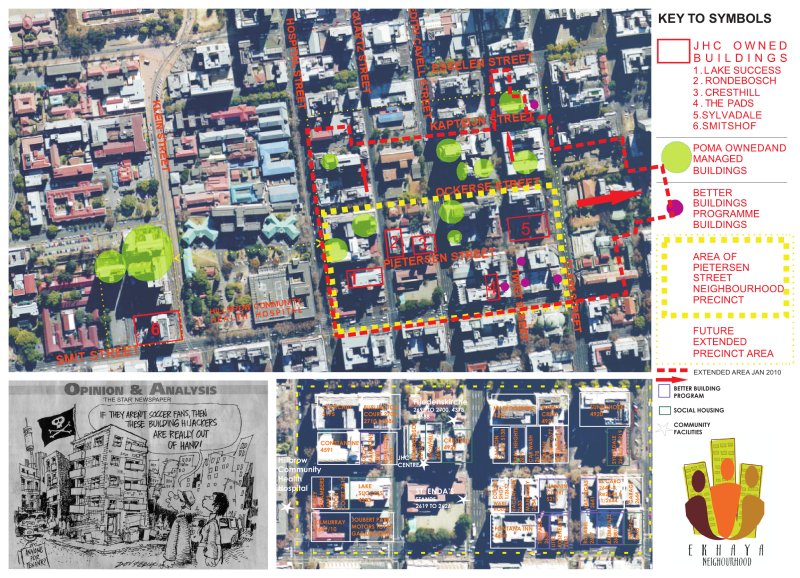

Exhibitor: Architects Collaborative cc - eKhaya Neighbourhood Project

Exhibitor: Savage + Dodd Architects - Inner City Movement Framework

Exhibitor: Monica Albonico and Lone Poulsen - Jeppe: ‘The Chaos Precinct’

Exhibitor: Dr Tanya Zack and Robyn Arnot - Recycle Change

Exhibitor: Tanya Zack/ Sarah Charlton/ Bronwyn Kotzen - Warwick Bridge

Exhibitor: designworkshop : sa

IN-SITU UPGRADING

- Besters Camp

Exhibitor: Harber & Associates - eThekwini Municipality

Exhibitor: eThekwini Municipality, Aurecon and Project Preparation Trust - Home Improvements

Exhibitor: FinMark Trust - Kliptown Explored

Exhibitor: Monica Albonico and Lone Poulsen - Lion Park

Exhibitor: Michael Hart Architects Urban Designers

CATALYTIC PROJECTS

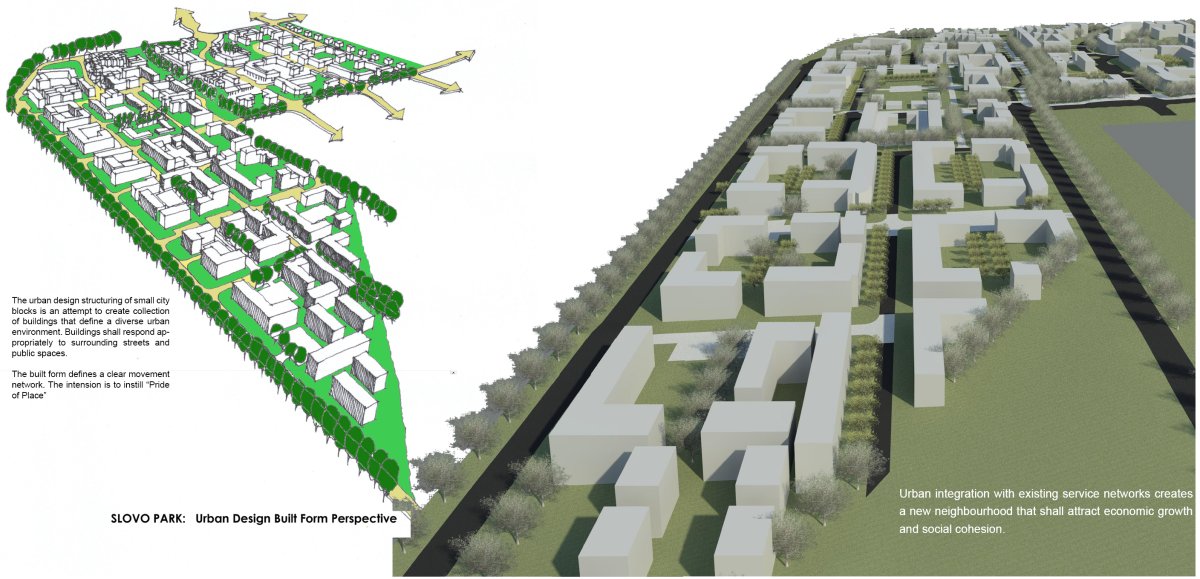

- Integrated Neighbourhood - Slovo Park

Exhibitor: Michael Hart Architects Urban Designers - SAPS Retreat Railway Police Station

Exhibitor: Makeka Design Lab - The Aesthetics of Safety

Exhibitor: Makeka Design Lab - Urban Acupuncture - Khayelitsha

Exhibitor: Makeka Design Lab

BACKYARD / OWNER INTERVENTIONS

Below is a brief excerpt from each of the projects in this category. Click on the links or image to see the full project panel details and illustrations.

Flats of Du Noon

Exhibitor: H. Wolff

Over the past decade, a new type of privately developed, rentable housing started emerging in Du Noon, Cape Town. As an economic model it is similar to the renting of backyard shacks, but the rentals are three times higher on average. The extraordinary income-generating potential of the flats in Du Noon and their morphological innovation is what sparked interest in this study.

Learning from our own backyard

Exhibitor: Lone Poulsen and Melinda Silverman

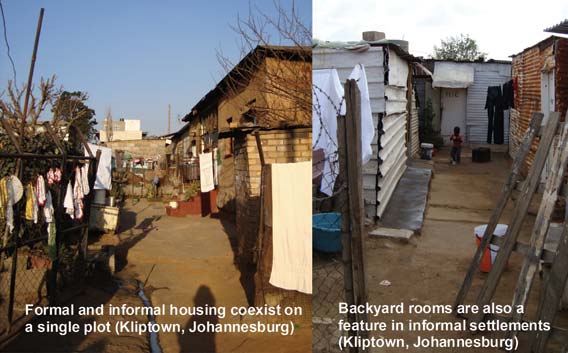

At the back of almost every formal house in South Africa is an additional building. This might be a servant's quarter, a granny flat, 'a room for rent', an informal shop, a spaza or a hairdressing salon . In many instances these backyard rooms have been informally developed built by the owners of the formal house in an attempt to derive income from their properties. Backyard rooms are a notable feature of the South African urban landscape and have a long history in South African cities

Flats of Du Noon

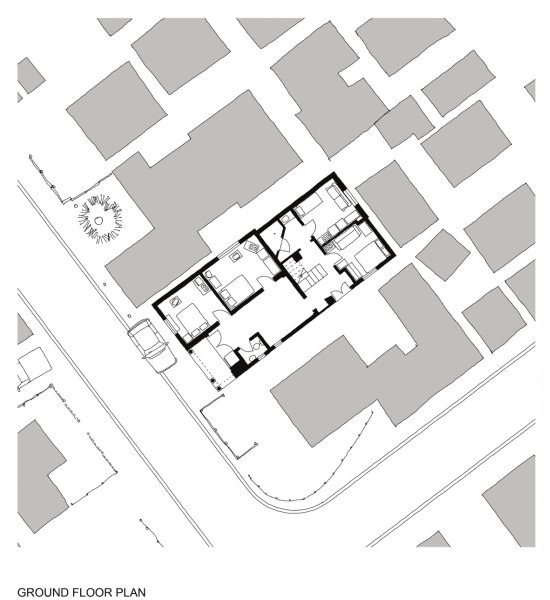

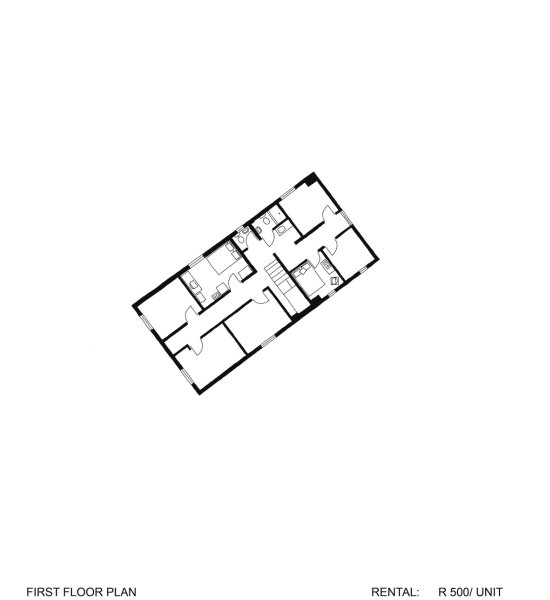

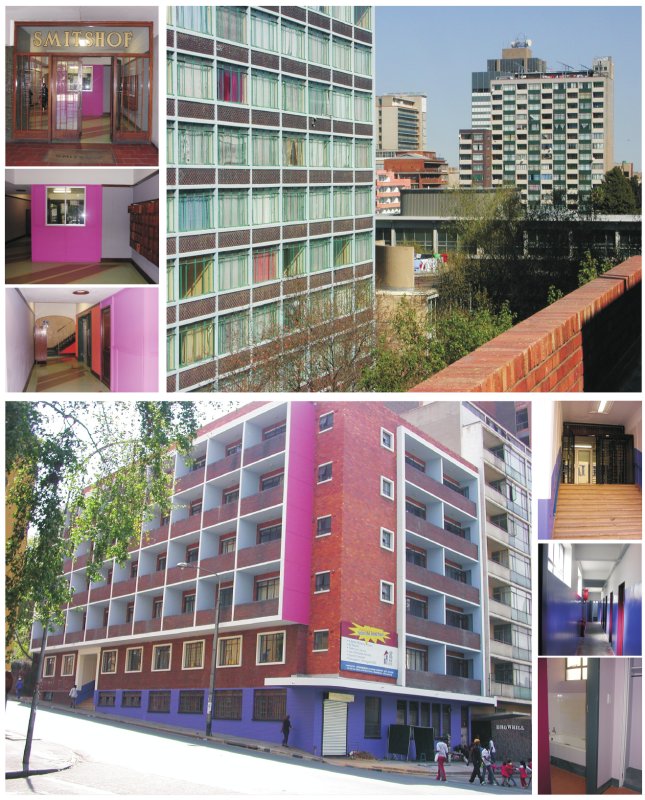

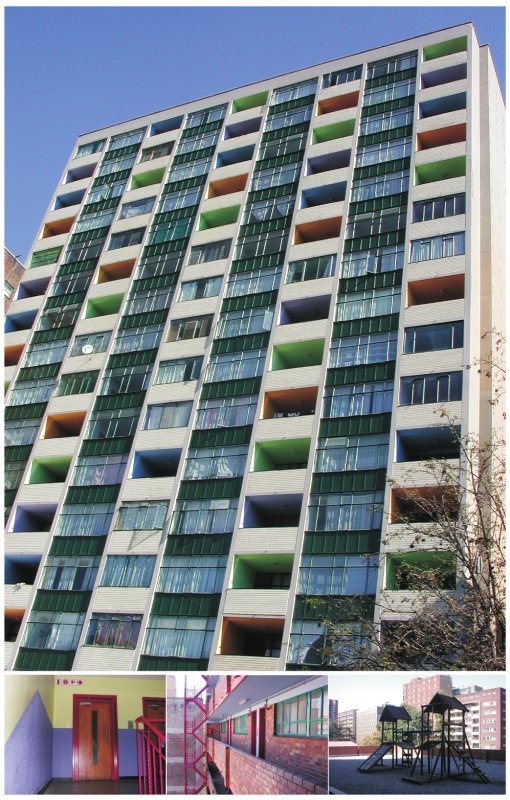

FLATS OF DU NOON

A study of owner developed rentable housing

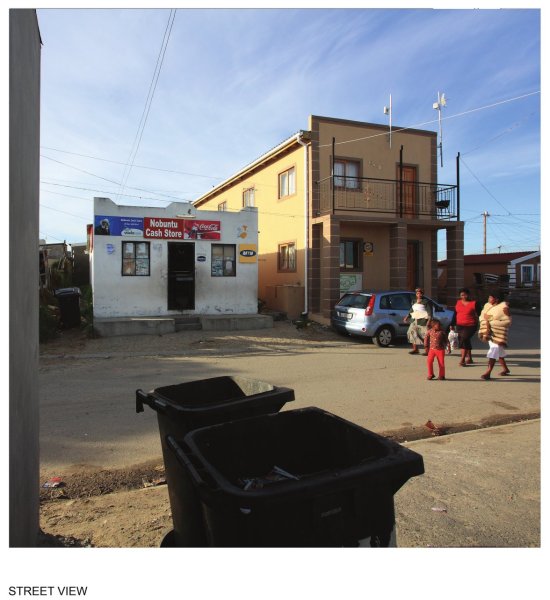

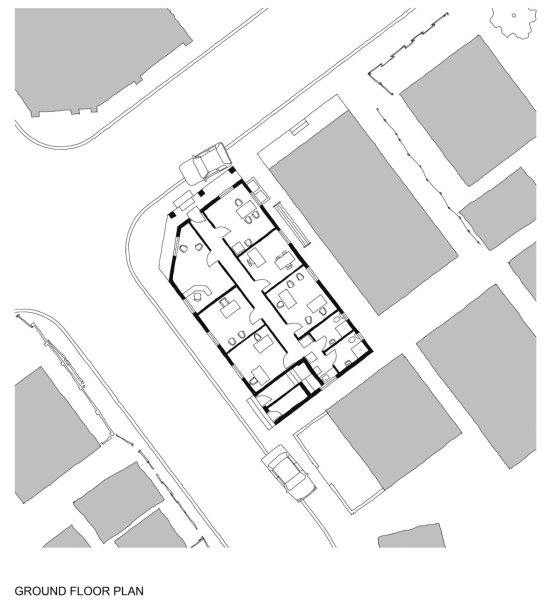

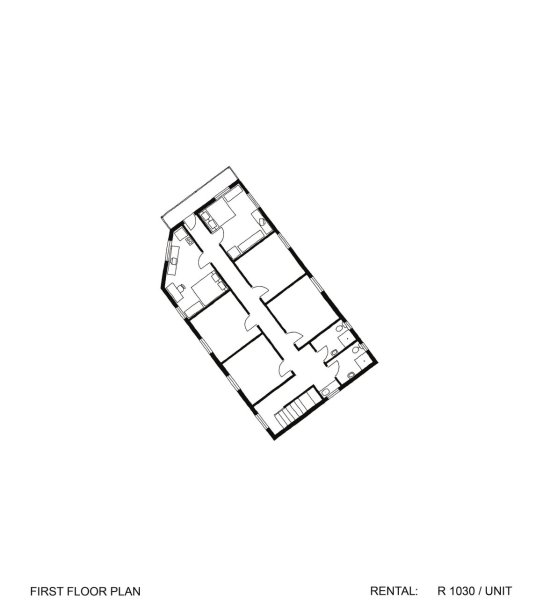

Du Noon, Cape Town 2010

Privately initiated and funded research by H. Wolff

Assisted by V. Loseby, M. Willemse, A. van Wyk and E. Gericke

Over the past decade, a new type of privately developed, rentable housing started emerging in Du Noon, Cape Town. As an economic model it is similar to the renting of backyard shacks, but the rentals are three times higher on average. The extraordinary income-generating potential of the flats in Du Noon and their morphological innovation is what sparked interest in this study.

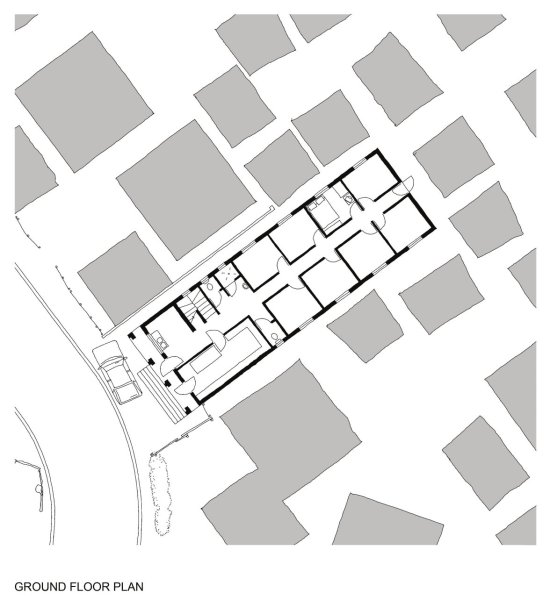

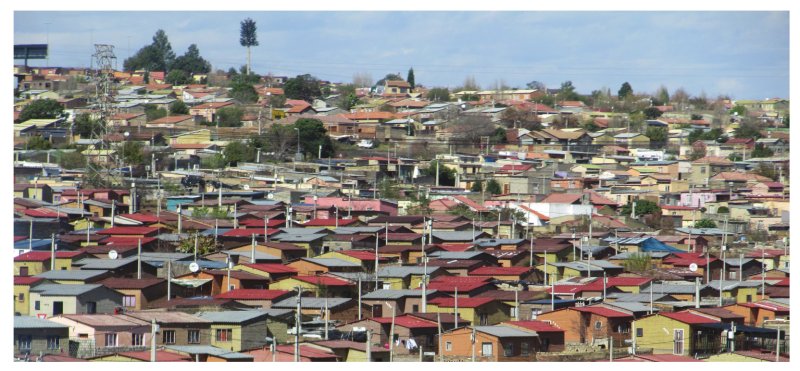

Du Noon is a Post-Apartheid settlement that owes its origins to a Provincial Governmental housing roll-out that started in 1996. Typically a 38m' RDP house would be built in the centre of a 115m' property. As an area for social housing, Du Noon is uncharacteristically well located near industrial, manufacturing, agricultural and residential job opportunities. The intensity of economic opportunity has resulted in rapid informal densification of Du Noon and the possibility to develop more permanently constructed, rentable apartments.

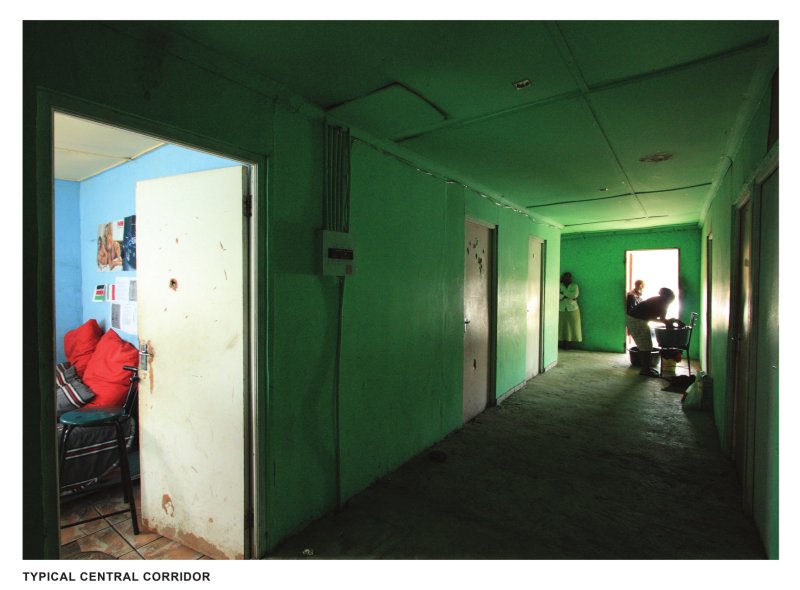

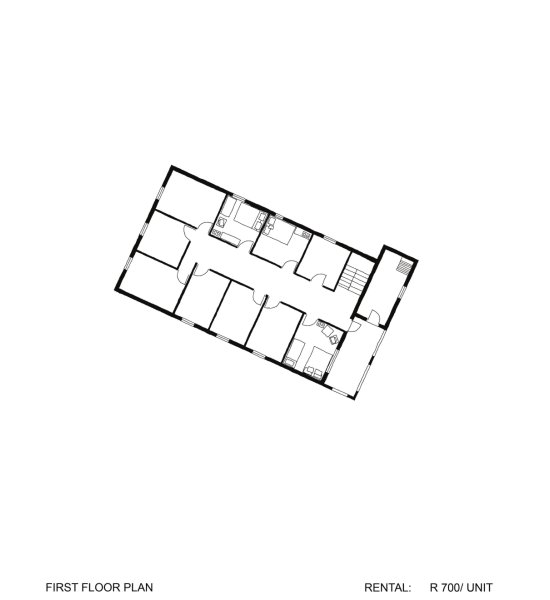

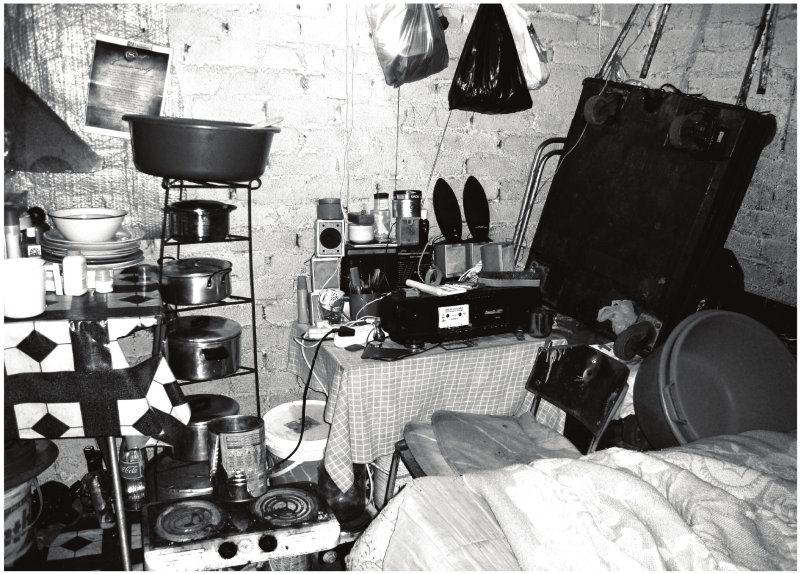

The Du Noon flats have developed a typical morphology that consists of a series of single room flats off a central corridor with shared ablutions. The flat sizes range between 6 and 13m2, with an average flat size of 8m'. The rentals for these flats range between R 400 - R 1030 per flat, with all flats being occupied in reasonably similar ways. Because of the consistent flat sizes, the content of each flat is typically a double bed, cupboard, couch or chairs, television , microwave, two plate stove and sometimes a fridge . The flats are occupied by between 1 and 4 people.

The development of these flats was financed in a variety of ways , but never with a bank loan. Some were financed with profits from vegetable or alcohol trade and others through stokvels. A common method of financing was to develop incrementaliy- completed flats were rented out while the remainder were still under construction.

All of the buildings in the study were constructed from masonry, with roofs made of timber beams and covered with roof sheeting. The internal floors were either timber beams and plywood boards or various forms of concrete floors. In general the buildings were built fairly well however, there are some violations of the National Building Regulations, most notably the fire regulations. The most common problems being a lack of a second means of escape and non-conformity with the stair designs. Most of these problems could have been overcome if the owners had access to professional advice.

Du Noon is zoned as 'Informal Residential'. This zoning has facilitated the development of rentable housing, due to it placing unlimited restrictions on the number of units per erf, provided that the primary use is for residential purposes. Many of the flat buildings have a shop on ground floor, one building even provides rentable office space. The mix of functions in these buildings, and the extreme density of flats per erf, has resulted in buildings that push right up to the road edge and therefore participates in the spatial definition of the street.

Due to Reception Area’s complex and dense urban fabric, the strategy is realized in three scales: an existing toilet upgrade, a medium-sized toilet and shower facility, and a large service centre with toilets, comfortable bathrooms, laundry and community services.

The large units are arranged around semi-private courtyards. Besides regular bathrooms, they contain retail spaces which could be used by a hairdresser, internet cafe, laundry, tuck-shop, crèche, gym, etc. The two roof terraces can be used for drying clothes and by the gym as outdoor exercising spaces respectively.

Through incorporating lessons learnt from the dynamic urban and architectural character of the Reception Area, the facilities are cross-programmed to offer multiple services and income streams. All typologies would provide business opportunities for local caretakers and operators.

Continued on Panel 2.

HEINRICH WOLFF

Flats of Du Noon (Panel 2)

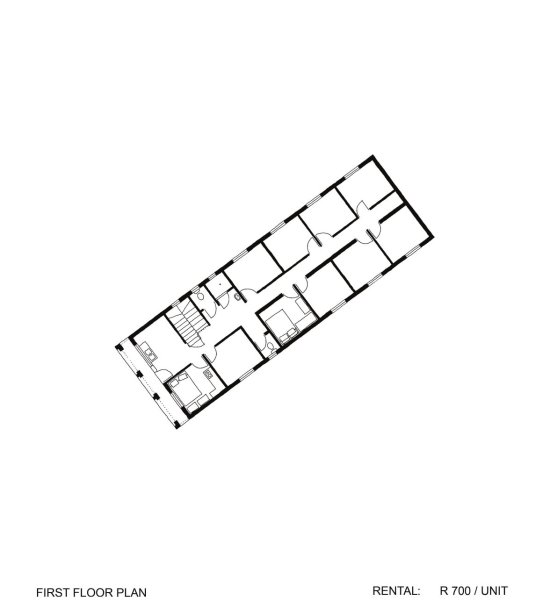

FLAT DATA

| Average unit size: | 8m2 | ||

| Typical rental: | R 700 / month | ||

| R 50 - R100 / m2 | |||

| R 45 - R 80 / m2 | (including ablutions) | ||

| Comparative rentals: | R 700 ÷ 8m2 | = R 88 / m2 | DU NOON |

| R 3500 ÷ 40m2 | = R 88 / m2 | CAPE TOWN CITY | |

| R 3000 ÷ 40m2 | = R 75 / m2 | BANTRYBAY | |

| R 3500 ÷ 40m2 | = R 88 / m2 | BANTRY BAY (upmarket) | |

| R 2850 ÷ 40m2 | = R 71 / m2 | BLOUBERG | |

| R 2650 ÷ 40m2 | = R 66 / m2 | DURBANVILLE |

Back to Panel 1.

HEINRICH WOLFF

Learning From Our Own Backyard

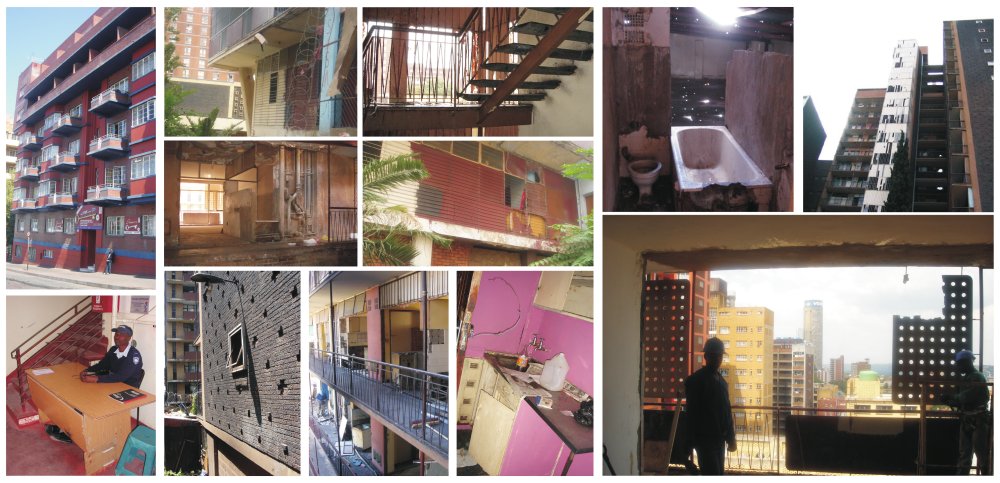

LEARNING FROM OUR OWN BACKYARD

Informal provision of affordable rental stock

Research conducted into backyard rental since 2002 for amongst others the GDoH and the NDoH

Lone Poulsen and Melinda Silverman

At the back of almost every formal house in South Africa is an additional building. This might be a servant's quarter, a granny flat, 'a room for rent', an informal shop, a spaza or a hairdressing salon . In many instances these backyard rooms have been informally developed built by the owners of the formal house in an attempt to derive income from their properties. Backyard rooms are a notable feature of the South African urban landscape and have a long history in South African cities:

Over a hundred years residents of Alexandra built clusters of rental rooms on their large peri-urban plots. This gave rise to the "Alex yard" which remains the primary social entity in Alexandra. In the townships developed by Apartheid government in the 1950s, residents gradually added backyard rooms in spite of state efforts to curb African urbanisation. New rooms were often disguised as "a garage and two stores" when such additions were illegal.

Today the pattern of building backyard rooms remains popular. Beneficiaries of the RDP housing programme rolled out by the post-Apartheid state have also been adding rooms at the backs of their plots. During the 1990s more new tenancies were created in the informal than the formal sector, most often in the form of backyard rooms. The 2001 census counted 460 000 households, or about 2.3 million people, living in backyard rooms. Until recently "backyard shacks" have been viewed in a negative light by the authorities - largely because the increase in density has placed significant strain on existing infrastructural services.

Although the quality of backyard rooms is often poor, this form of accommodation - built entirely without government help - offers potential solutions to a number of South African housing problems.

1. The addition of backyard rooms helps to increase housing density, which means that urban land is used more efficiently. The same amount of road space and the same length of pipe runs can be used to serve additional households. Increased urban densities also generate higher thresholds for public transport, retail and social services making these amenities more viable. Additional rooms on the plot often help to define better outdoor space, creating courtyards where children can play and residents can socialise.

2. The addition of backyard rooms allows the owner of the primary dwelling to derive income from his/her property in the form of rental rooms or home enterprises. This means that a house provides more than shelter and also functions as an economic generator. This increases the asset value of the property.

3. The addition of backyard rooms provides accommodation that is more responsive to diverse household arrangements where families are rarely nuclear - mom, pop and 2.5 kids - but more likely to comprise grannies looking after AIDs orphans, extended families , women headed households, and multiple households.

4. The addition of backyard rooms improves the supply of much-needed affordable rental accommodation, fulfilling the needs of an estimated 80% of the population who cannot afford formal rental housing. Cheap rental options are necessary in the context ongoing migrancy where work in cities, but maintain links with families elsewhere and in the context of increasing labour mobility where urban residents are forced to move in search of jobs.

5. From a municipal perspective backyard rooms are a far less alarming manifestation of informality than freestanding shacks which are often erected on inappropriate or unsafe land. Backyard rooms are built on land that has already been zoned as residential.

It is for these reasons that backyard rooms are increasing being seen as a solution to South Africa's housing shortage rather than a problem.

Continued on Panel 2

.

LONE POULSEN: ACG ARCHITECTS & DEVELOPMENT PLANNERS

MELINDA SILVERMAN: DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE: UJ

Learning From Our Own Backyard (Panel 2)

LEARNING FROM OUR OWN BACKYARD

New models of affordable housing

Research conducted into backyard rental since 2002 for amongst others the GDoH and the NDoH

Lone Poulsen and Melinda Silverman

The backyard room is receiving increasing attention from South African policy makers and design professionals as a potential solution to some of South Africa's most pressing housing problems - excessively low densities, a shortage of affordable rental housing, housing units designed only for nuclear families.

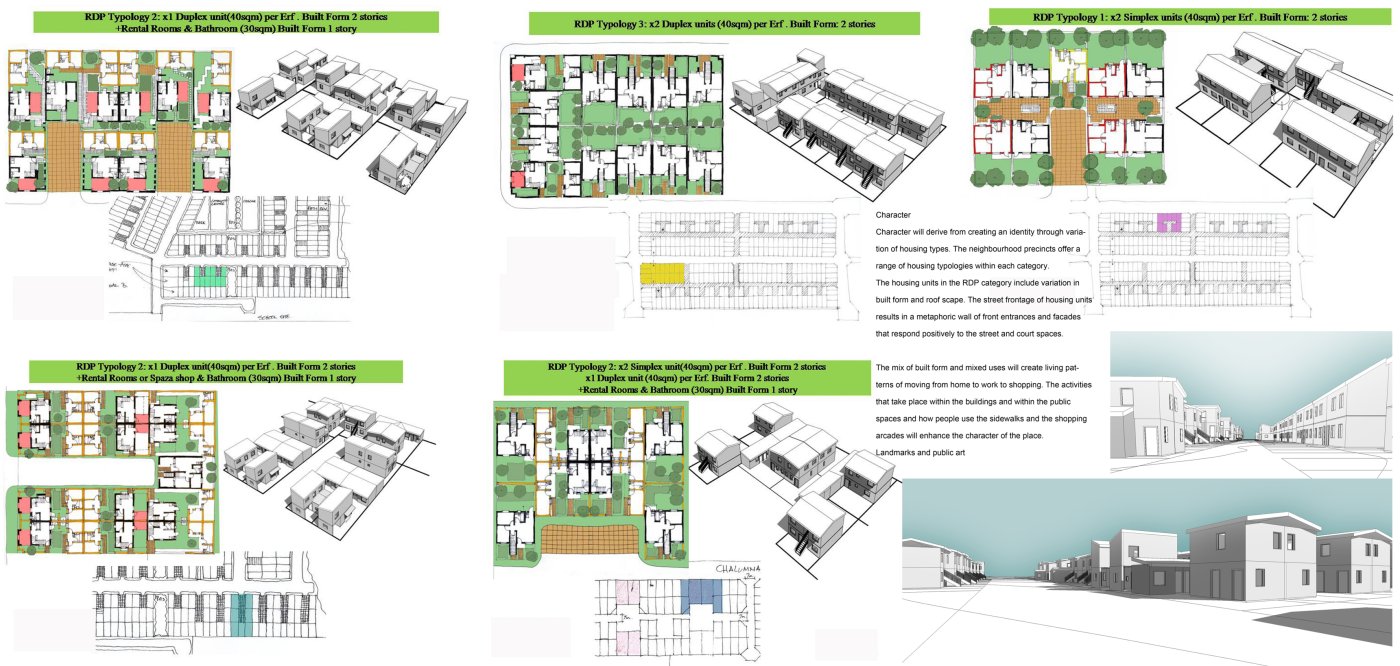

Informed by these theories and observations of organically developed backyard rooms, architects and urban designers have started to develop housing models that anticipate and make provision for backyard additions. These new housing prototypes harness the advantages of backyard accommodation while seeking to mitigate the disadvantages associated with unplanned, unanticipated densification.

These new models are characterised by:

Reduced plot sizes. This ensures that urban land - an increasingly scarce resource - is used more efficiently.

Narrow street frontages. This reduces the amount of road space and pipe runs needed to serve individual plots. This results in significant savings in both the capital and operating costs of services.

Unorthodox siting of the starter unit. Rather than locating the house in the middle of the plot, as per conventional suburban housing, the starter unit is located near the front of the site and along one of the side boundaries. This immediately creates an identifiable street edge, allows for street-related commercial activities like

spazas, maximises the amount of useable outdoor space, and ensures that adequate space is available at the back of the site for the incremental addition of backyard rooms.

Building the starter unit as a double storey. This ensures that the building footprint is reduced maximising the amount of outdoor space.

The advantages of these new housing models are manifold:

They increase densities and therefore make more effective use of infrastructure;

They can be developed incrementally as the primary homeowner acquires more capital;

They harness the entrepreneurial talents of the community and provide jobs for small contractors;

They disperse political risk amongst a large number of small landlords;

They accommodate a wide variety of living arrangements on the same plot - multiple households, home-based enterprises, a mix of freehold and rental tenure.

These principles have already been realised in a number of exemplary projects across the country:

In the PELIP project in Nelson Mandela Bay, Noero Wolff developed a row house typology with two and three storey units. Each unit was conceptualised as a starter house, designed to allow beneficiaries to customise their housing in accordance with their own requirements. Units are narrow and built right up against the street edge, allowing for flexible space in the back yard to accommodate additions or rentable rooms.

In the Far East Bank project in Alexandra, in Johannesburg, ASA Architects developed clusters of six to eight units with a mix of double storey main houses and single storey rental rooms. Some beneficiaries are renting out the rooms to tenants and some are using the rooms to operate small businesses. The road space within each cluster functions as a contained courtyard proViding a safe space for children to play.

In the 10x10 project in Freedom Park, a suburb in Cape Town, MMNLuyanda Mpahlwa architects developed two-story timber frame and sandbag infill row houses, designed and built with community involvement. The houses are placed close to one another on the street edge, immediately contributing to a sense of urbanity.

In Lufhereng, in Mogale City, 26°10 South and Peter Rich Architects created row-houses comprising single and double-storey units which afford a sense a variety. The houses are built close to the street edge with private gardens at the back. The use of smaller-than-usual stands has helped increase residential densities and some residents have already converted rooms into tuck-shops and hairdressing salons.

Back to Panel 1.

LONE POULSEN: ACG ARCHITECTS & DEVELOPMENT PLANNERS

MELINDA SILVERMAN: DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE: UJ

CATALYTIC PROJECTS

Below is a brief excerpt from each of the projects in this category. Click on the links or image to see the full project panel details and illustrations.

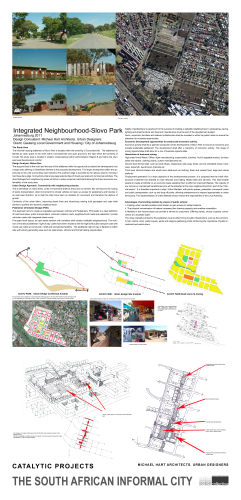

Integrated Neighbourhood - Slovo Park

Exhibitor: Michael Hart Architects Urban Designers

The informal housing settlement of Slovo Park is located within the township of Coronationville. The settlement is flanked by open space to the north within Coronationville and open ground to the east within the township of Crosby.The study area is located in western Johannesburg within Administration Region B and within the city's east west development corridor.

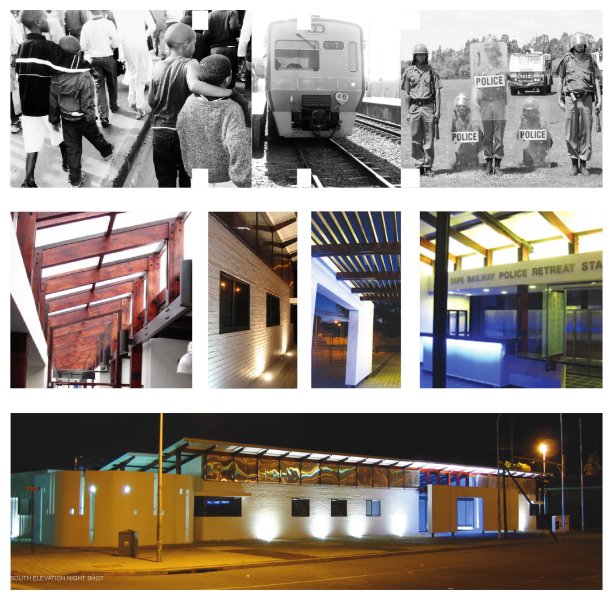

SAPS Retreat Railway Police Station

Exhibitor: Makeka Design Lab

The Retreat Railway Police Station acknowledges that a better public engagement can be fostered by fashioning spaces and environments that promote transparency and visibility, which are open and welcoming, and most importantly are safe and accessible. The building plays its part in the narrative of a better, more efficient and more connected South African Police Service to be used and accessed by the citizens it serves.

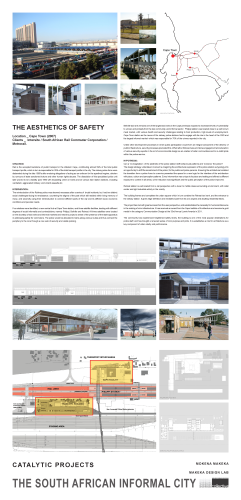

The Aesthetics of Safety

Exhibitor: Makeka Design Lab

Rail is the accepted backbone of public transport in the Western Cape, contributing almost 59% of the total public transport profile, which in turn is responsible for 29% of the total transport profile in the city. The railway police force were disbanded during the late 1980’s after enduring allegations of acting as an enforcer for the apartheid regime, stricken by rumours of state sanctioned torture and other human rights abuses. The dissolution of this specialised police unit later proved to be a liability post 1994 with escalating crime on trains and at various train station stations, including vandalism, aggravated robbery, and violent assaults etc.

Urban Acupuncture - Khayelitsha

Exhibitor: Makeka Design Lab

Khayelitsha is the largest and last township to be formally established in the Western Cape. Located at the heart of the Cape Flats and abutting Mitchel’s Plain, its narrative of dislocation, hope, and unequal access to resources, amenity and infrastructure positions the area as an exemplar of Apartheid informed informality. President Thabo Mbeki identified it as one of twenty national urban renewal nodes with a specific role to play in terms of social cohesion, upliftment and integration across the fractured cultural divide. The central business district was conceived to create a new urban room, an inspirational public realm for a devastated and desolate community lacking any resilient hierarchy of formalised ‘publicness.’

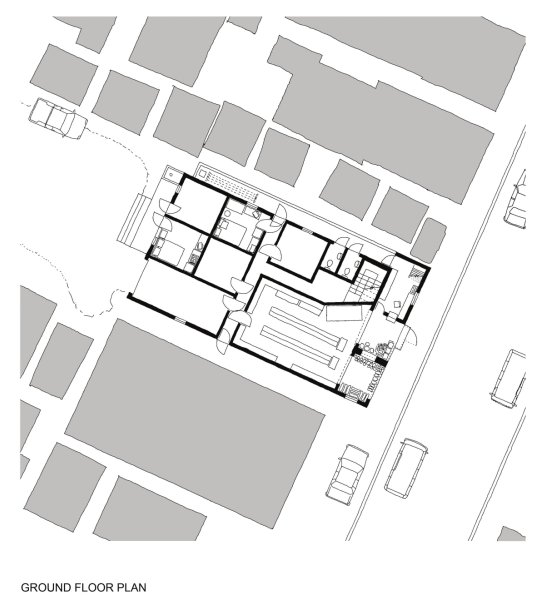

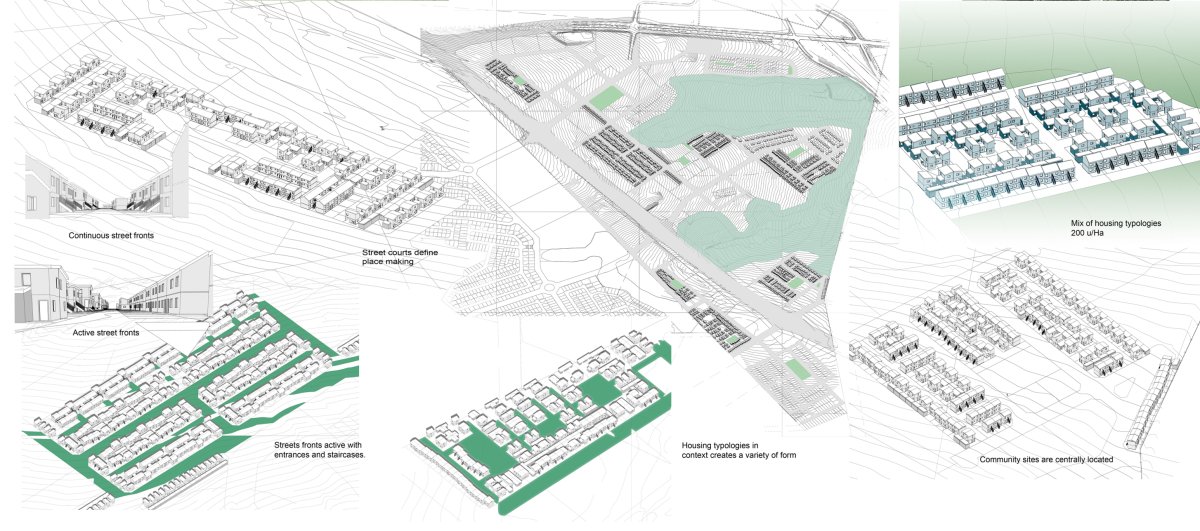

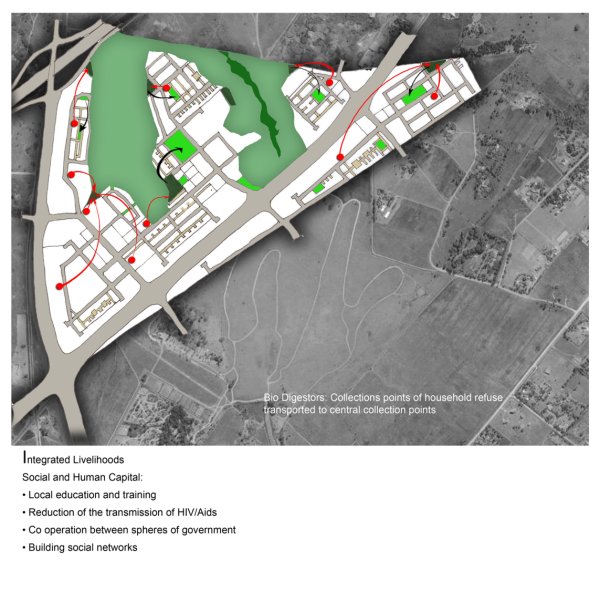

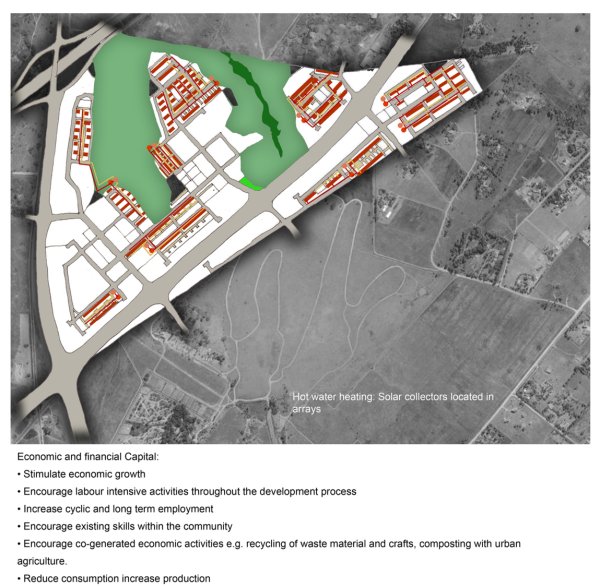

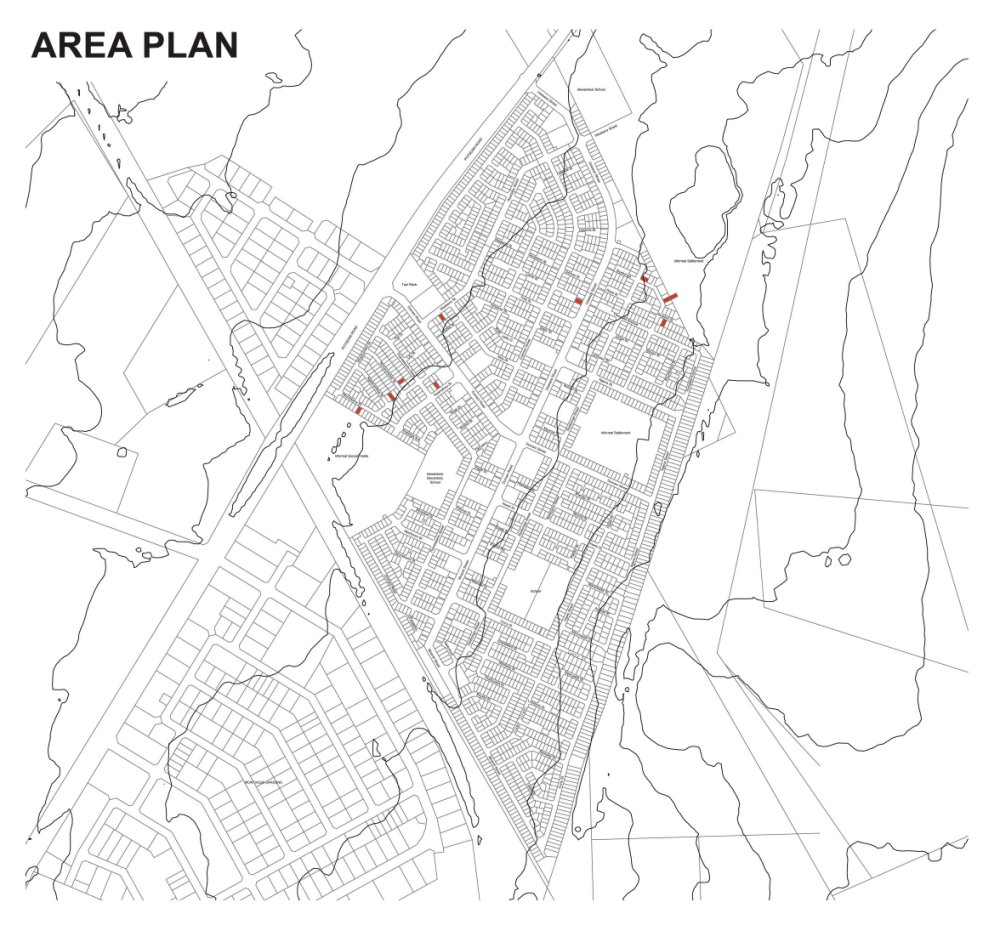

Integrated Neighbourhood - Slovo Park

INTEGRATED NEIGHBOURHOOD - SLOVO PARK

Johannesburg 2011

Design Consultant: Michael Hart Architects. Urban Designers

Client: Gauteng Local Government and Housing / City of Johannebsurg

The Study Area

The informal housing settlement of Slovo Park is located within the township of Coronationville. The settlement is flanked by open space to the north within Coronationville and open ground to the east within the township of Crosby.The study area is located in western Johannesburg within Administration Region B and within the city's east west development corridor.

Design Analysis :Status Quo

The acquired land to the north and the east of the settlement offer the opportunity to extend the development over a larger area offering a Greenfields element to the proposed development. The larger development offers the opportunity to link with surrounding road networks.The southern edge is bounded by the railway reserve , forming a hard boundary edge. Connectivity shall encourage opportunities of mixed use retail and commercial activities. The direct linkages from neighbouring areas will inform a wider consumer catchment allowing the future economic sustainability of the study area.

Urban Design Approach: Connectivity with neighbouring suburbs.

This is beneficial on many levels. Lines of movement shall be direct and convenient; this will improve the routing of public transportation, direct movement for private vehicles wil open up access for pedestrians and bicycles in an east west direction, up to date the sites have been an obstacle for movement and therefore the decline of growth.

Continuity of the urban fabric, improving desire lines and introducing varying built typologies and uses shall achieve a positive and dynamic neighbourhood.

Pedestrian Orientated Design (POD)

This approach aims to create an equitable use between Vehicle and Pedestrians. POD leads to a clear definition of road hierarchies, public transportation , vehicular collector roads, neighbourhood roads and pedestrian / private vehicular roads with integrated street courts.

Fine grain block layout, an open street network with variations shall create a walkable neighbourhood. The inclusion of mid block pedestrian "right of way" paths have been inluded to link the high level public transport route with mixed use nodes of community / retail and recreational facilities . The pedestrian right of way is flanked on either side with activity generating uses such as retail shops, informal and formal trading opportunities.

Safety of pedestrians is paramount to the success of creating a walkable neighbourhood. Landscaping, paving, lighting and street furniture and long term maintenance must be part of the development budget.

Socio -economic functions and relevant infrastructure shall be invested in within the public realm to ensure the attraction for business opportunities.

Economic Development opportunities for small scale economic activity.

Economic activity shall be a planned component of the development of Slovo Park to ensure an economic and socially sustainable settlement. The development shall offer a hierarchy of economic activity. The range of zoning opportunities shall allow for a mix of business opportunities.

Hierarchies of business zoning:

High order formal Retail/Office / light manufacturing: supermarket, butchery, fruit &vegetable traders, furniture sales and repairs, clothing chains, curtain manufacturers etc;

Second level formal retail: such as small shops, restaurants, take away foods, service orientated shops: hardware, locksmith, laundromat, chemists etc

Third level informal traders and small micro stalls:such as clothing, fresh and cooked food, bags and phone stalls etc

Employment generation is a major objective of the developmental process. It is proposed that the initial infrastructure

investment be directed to road networks and trading related sites and services. This shall enable people to create a foothold on an economic basis assisting them to afford an improved lifestyle. The majority of low income or unemployed beneficiaries who will be attracted to this new neighbourhood form part of the "informal sector". It is therefore important to align 'Urban Markets' with public spaces; pedestrian movement routes and public transportation, pick up and drop off points, allowing entrepreneurs to respond appropriately to urban structuring . The implementation of Urban Markets should remain the responsibility of the Local Authority.

Advantages of promoting markets by means of public actions:

i. Creating urban markets enables small traders to gain access to viable locations.

ii. The physical concentration of traders increases their drawing capacity and enables competition .

iii. Markets in low-income areas can provide a service to consumers. Offering variety, choice of goods, convenience at a localised scale.

The urban markets is linked by the pedestrian route to other forms of public infrastructure, such as the community hall, creche, clinic, public square, parks and religious gathering points reinforcing the importance of public investment and social return.

Continued on Panel 2 | Panel 3 | Panel 4.

MICHAEL HART ARCHITECTS URBAN DESIGNERS

Integrated Neighbourhood - Slovo Park (Panel 2)

INTEGRATED NEIGHBOURHOOD - SLOVO PARK

Johannesburg 2011

Design Consultant: Michael Hart Architects. Urban Designers

Client: Gauteng Local Government and Housing / City of Johannebsurg

Public Realm Investment

The public realm offers a multifaceted element to the development of neighbourhoods. The public realm shall offer choice and diversity for people who live, work or visit the neighbourhood.

The public realm shall be designed to respond to the users needs, enhance new opportunities and encourage a sense of pride and ownership. This will achieve a respect for the environment and improve economic sustainability and future economic growth of the initial investment.

The environment shall be designed to encourage activity and positive social interaction. The architectural character shall be one that responds to the local climate, demonstrates innovative use of materials, colour and texture. Public facilities shall be located so that they respond to hierarchies of transportation and are within walking distances.

Accessibility

The neighbourhood is seen as an extension to the existing suburbs of Crosby and Coronationville. The seamless linkages between the new neighbourhood and its surrounding context shall encourage accessibility of the many shared facilities within the region.

Place making

The proposed development site is geographically featureless. The changes in ground level at the man made embankment shall be utilized to create a green belt and a potential vantage point for the buildings along its east west axis.

The site fa lls gradually from the north to the south, making east west movement more convenient to walk and build along. The relatively small city block configuration will facilitate for a pedestrian orientated environment. The corners of blocks and street intersections become social spaces and opportunities for corner shops and architectural expression.

Social gathering spaces and places of economic activity are located along pedestrian movement corridors, becoming activity spines linking with the higher order movement system.

The major linking road that links Crosby with Corronationville becomes the 'high street' running in an east west direction. The street will accommodate buses and taxis. Buildings along the eastern section of the street shall offer shopping with possible office space and residential apartments on the upper floors. Parking shall take place behind the shopping strip within the inner courtyard. Street parking is proposed along both sides of the road with a colonnaded sidewalk fronting the shops. The 20m road reserve shall accommodate major traffic with the inclusion of a bicycle lane on the southern side of the street. The street shall be well treed with street lighting and furniture along sidewalks.

Symbolic statements and public art are important elements that should be encouraged as these objects and spaces become landmarks and places of meaning and significance.

Public spaces must be seen as primary spaces with neighbourhoods where people interact and experience urban life. Public spaces wi thin lower income neighbourhoods are desirable spaces as they function as extensions to their private residents. It becomes an important element that compliments higher density living conditions. In most high people-density environments the public spaces including residential streets shall be designed as social spaces.

'Streets as public spaces have historically been the carriers of people. Pedestrians on foot often spend more time in street spaces than people in vehicles. The introduction of ' street courts" within neighbourhood roads offers residents a public I social space that is defined for the multi-use of vehicles and social interaction creating small scale nodes for smaller groupings.

Urban Design Sustainability

'There are a number of sustainability categories that should be taken into account at the Urban Design level of development. The overarching concept of sustainability is to ensure that the initial decisions and actions embarked on create opportunity and viability for current and future generations.

Economic sustainability.

Develop opportunities within the public realm for economic based enterprise to take place, from informal traders, recycling and light manufacturing, small retailers and food traders to medium scaled retail and commercial facilities.

Social sustainability.

Create a public realm that offers well defined, friendly outdoor spaces that allows for social interaction, active events, and quiet contemplation. Include public facilities and amenities that encourage cultural, educational and recreational activities. Create accountability from community members and the local authority to ensure efficient management and long term maintenance.

Environmental sustainability

The green network shall fall within landscape guidelines to ensure ecological bio-diversity. The planting of grasses and shrubs in parks, street trees, streetscapes and courtyards shall be planned with hard and soft surfaces. A management strategy for landscape, waterways I storm water channels and grey water shall be considered.

Panel 1 | Panel 2 | Panel 3 | Panel 4.

MICHAEL HART ARCHITECTS URBAN DESIGNERS

Integrated Neighbourhood - Slovo Park (Panel 3)

INTEGRATED NEIGHBOURHOOD - SLOVO PARK (PANEL 3)

Urban Design Principles and Criteria

Johannesburg 2011

Design Consultant: Michael Hart Architects. Urban Designers

Client: Gauteng Local Government and Housing / City of Johannebsurg

Connectivity

Connectivity is an important principle towards new livable neighbourhoods’. It is a major component of the future success through integration. The need to integrate from an economic, transportation and social perspective is to gain access to public facilities, movement routes, business and trading facilities that will create high levels of functionality within the development.

Continuity

Continuity of movement systems that link neighbouring nodes must serve the new neighbourhood in drawing energy into a new activity spine that slows down traffic and allows for stopping of busses, taxis and private vehicles. Continuity shall apply to movement, built form, public space and green spaces.

Movement Network

The major public transport route through Slovo Park encourages a continuation for metro busses to move through a circular loop within the new neighbourhood. The low level of car ownership within the neighbourhood necessitates for an efficient public transport route with convenient stops.

Stops shall be located at retail points, community facilities within the development and adjacent to the existing schools in neighbouring Coronationville.

Movement routes shall linking with the traders market and public facilities.

Low order access roads shall incorporate social spaces and pedestrian street courts.

Activity nodes and spines

The pedestrianised activity spine shall link the business and transportation nodes.

Public space and community facilities

Public spaces shall be implemented in a number of different forms. Open-air spaces, parks and squares shall be well defined. These spaces shall be located adjacent to community centres, crèches or churches allowing for a synergy sharing of uses.

Education and Child care

The development shall rely on the sharing of neighbouring schooling facilities. The inclusion of new preschooling facilities and crèche facilities shall be developed with community centres and community halls.

Health

The location of a community clinic within the development is vital in achieving convenient access within walking distance of all the new residential unit.

Religion

The incorporation of a prominent site for a church building may become a community building with shared uses and facilities. The church is located adjacent to the community centre with a public open space between them. This relationship shall reinforce the identity of ‘place making’ for a new community.

Important community buildings will create landmarks and reference points of a unique character.

Green Network

Creating a Green Network is in response to a basic human need for the natural landscape. The built environment requires a balance between hard construction and soft natural landscape. The environmental importance is to promote and improve natural ecologies, bio diversity, filtering of pollution and natural cooling of urban environments.

The importance is that green spaces are continuous allowing ecological systems to develop throughout the neighbourhood.

Parks are manageable in size ensuring that continual maintenance by the city is possible. Parks are designed as usable spaces and are located within close proximity to community and public facilities. Parks shall be linked with continuous tree planting along pedestrian linkages and sidewalks.

‘Street courts’ alongside residential blocks shall be well treed with indigenous trees creating shaded areas for recreation and play.

Courtyards within residential blocks shall include soft landscaping to enhance the environmental conditions for residents to develop safe and secure children’s play areas.

Key Strategic Objectives

Stitching the urban grid

The urban grid is a movement and services network. The locale of Slovo Park is an opportune infill development between two existing neighbourhoods. The stitching of the urban grid refers to knitting together network systems. Physical movement paths for public transportation, non motorized movement and points of access. It encourages social cohesion, and enhances the connectivity of a disenfranchised community with a broader society. It brings with it infrastructure and services. Integration brings identity and an the independence of getting an address. It brings a sense of recognition and pride.

The ‘knitting together ’of urban areas offers residents choices of transport including walking and cycling to reach a greater variety of amenities.

The grid formation of the proposed neighbourhood is one of a multi-directional public right-of-way network. This allows for motorised transport on a lower order with mixed-mode transport at a reduced speed.

Panel 1 | Panel 2 | Panel 3 | Panel 4.

MICHAEL HART ARCHITECTS URBAN DESIGNERS

Integrated Neighbourhood - Slovo Park (Panel 4)

INTEGRATED NEIGHBOURHOOD - SLOVO PARK (PANEL 4)

Johannesburg 2011

Design Consultant: Michael Hart Architects. Urban Designers

Client: Gauteng Local Government and Housing / City of Johanneburg

Walkability and pedestrian friendly environments

While acknowledging the motor vehicle and its requirements roads shall vary in size reducing in width as the capacity of vehicles reduces. The urban grid allows for vehicle access to all sites, the road pattern and block sizes are based on walking distances and multi-purpose uses for all roads.

The urban layout of smaller blocks within a multidirectional network generates more corners and therefore more stopping of vehicles allowing frequent pedestrian crossings.

Block sizes and block shapes

Block sizes in general shall be less than 100m in length. Walking distances to amenities and transport stops shall not be more than 400m or a 5 minute walking distance. Block shapes are generally square in shape with rectangular blocks along an east west orientation allowing a maximum northern aspect and aligning with an east west contour. The intention is that an entire block shall be accommodated by one development either housing or retail or a mixed use building. The benefit of the smaller block is that it has more exposure to street frontages giving more opportunity for the buildings to respond positively to the streets therefore enhancing the quality of the street.

Urban Design Criteria and Development Guidelines

Density

Development density affects a number of structural development objectives.

Density and Public Transportation

Public transportation is reliant on people density. In order to extend current transportation systems into the new neighbourhood.

The generally accepted status is that the more residential and employment opportunities the more passengers per kilometre and therefore the more frequent services are required.

Density and Employment

The current determination for South Africa is the creation of employment to arrest the cycle of poverty and the increasing social burden on the state.

This integrated neighbourhood design should take cognisance of the need to create employment activities within its community. Businesses and employment activity shall be clustered within a nodal zone in order to create a critical mass. This will ensure a destination for similar activities and support cost effective and convenient public transport.

Residential Densities

The residential component is based on a medium to high ratio of dwelling units per Hectare. Given the housing backlog and the need for a QUANTITATIVE goal this proposal shall be seen within a holistic integrated approach resulting in a QUALITATIVE outcome.

Integrating built urban spaces

The urban structure defines linkages through an open space systems. The pedestrian network links urban squares that are inter linked with other modes of movement. The success of this system is in its clear definition of visible and perceptual connectivity. The open space system is integrated into urban spaces to encourage an environment that is functional, pleasing and memorable. Architectural elements such as thresholds to buildings become transition zones between public and private spaces.

Robustness

The built form shall be constructed for durability and low maintenance. Public spaces shall be finished with good quality materials and thoughtful construction detailing to ensure longevity.

Active streets

All buildings facing onto public spaces shall be designed to facilitate activity. Blank facades and parking strips reflect negatively and create the perception of insecurity and attract negative influences. Entrances,windows and balconies create activity on the street facade and therefore improve security.

Build to edges

The principle of building to edges is to ensure a positive built form and continuous facades. Mixed use buildings shall be built with zero building lines and encourage canopies or covered walkways. Residential buildings shall be built on 2 or 3 meter building lines creating ease of surveillance of the public street.

Streetscapes

Built form shall be utilized to reinforce continuity and rhythm of street facades. Streetscapes shall be enhanced with street furniture, clear well designed and well located signage. Street lighting shall be located at entrance ways, pedestrian walkways, squares, bus stops and road intersections etc.

Bicycle lanes

Non Motorised transportation shall be encouraged. Cycling tracks shall be a dedicated 1.5m lane located between the road and footway on higher order roads. Localized connector roads shall be designed with cycling tracks on one side of the road.

Inner courts

The proposed built form for the development is perimeter blocks with inner courtyards. Where pavilion type buildings are designed separate pavilions shall be located in such a way as to create edge conditions to the site with well defined inner spaces. The design principles is to avoid creating loose undefined “lost” space which so often becomes derelict due to residents not taking ownership of them. These spaces are often become dangerous and attract negative social behaviour.

Panel 1 | Panel 2 | Panel 3 | Panel 4.

MICHAEL HART ARCHITECTS URBAN DESIGNERS

SAPS Retreat Railway Police Station

- click images to see larger version -

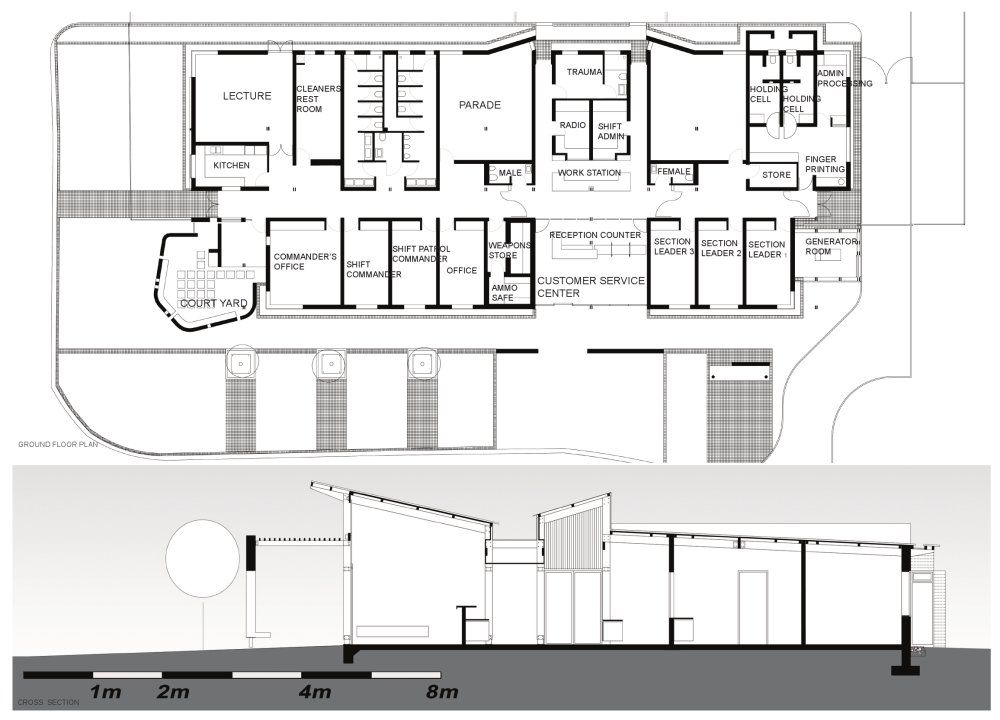

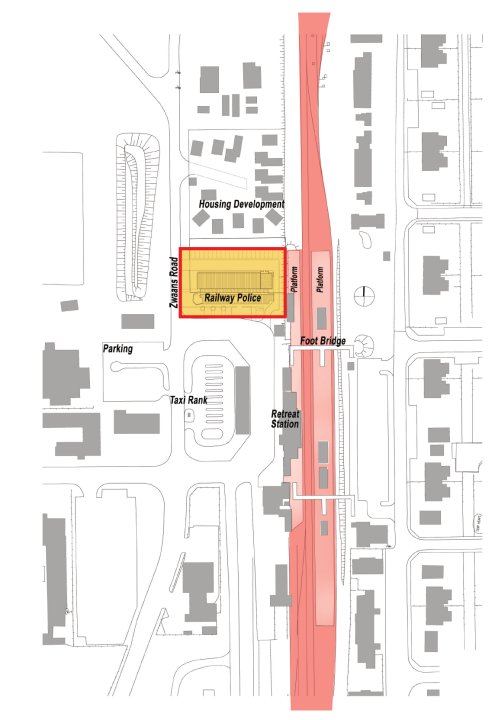

SAPS RETREAT RAILWAY POLICE STATION

Location: Retreat Cape Town (2007)

Clients: South African Rail Commuter Corporation / South African Police Service

MOKENA MOKEKA / HOLGER DEPPE

MAKEKA DESIGN LAB

The Retreat Railway Police Station acknowledges that a better public engagement can be fostered by fashioning spaces and environments that promote transparency and visibility, which are open and welcoming, and most importantly are safe and accessible. The building plays its part in the narrative of a better, more efficient and more connected South African Police Service to be used and accessed by the citizens it serves.

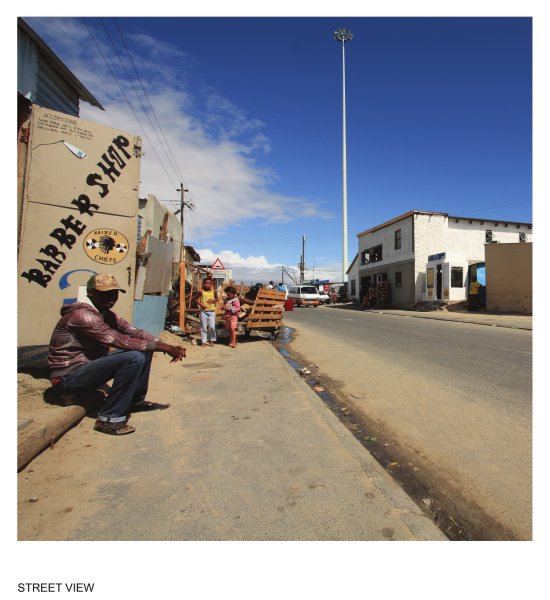

The client SARCC (today: PRASA) has chosen strategic locations at major junctions within the Western Cape Rail network for four new Railway Police Stations in order to improve safety and security for railway customers. One of these is Retreat, a low income suburb in the Cape Flats.

The police station provides the northern edge to an existing square in front of the railway station. The square is largely occupied by a taxi rank. The surrounds consist mostly of low scale commercial and light industrial development. Low income housing stretches from the other side of the railway line onwards.

During Apartheid, Institutions were entrenched for the use and protection of a limited minority group. After 1994 the country has been faced with the challenge of the reconstruction of institutions to serve the needs of a greater majority – such as the Constitutional Court. Retreat Police Station makes a valuable contribution to an approach that redefines the police station building typology of South Africa.

Police stations need to represent safety and security instead of the historic representation of a force of fear and oppression. This is achieved through a design language of transparency, identity of service and well-being. The building has a strong presence flanking the station square with its entrance marked by a screen wall and a glazed entrance foyer. The entrance and foyer with its service desk are directly visible to the taxi rank and other public zones and invite rather than repel. Through its openness and choice of material the design response fosters a sense of pride and encourages dignity and self respect.

The building’s simple rectangular form provides a strong, well-scaled edge to the square while the articulation of its ends provides formal interest. The building achieved a high degree in cost effectiveness through a minimalist approach to construction and material. This is reflected in the timber structure under use of SA pine and carefully designed connecting elements in steel. A transparent multiwall product was used for all clerestory glazing. From inside the foyer, SAPS operations are visible and sensible through the lowered screen behind the service desk.

The mystery of light is explored both in an effort to create a design that excites the imagination and that changed with the changing light of the day. It is a civic structure that is delicate at the human scale.

The environment created by this police station is that of openness and provision of service to the people. The sense of dignity reflects itself by the high acceptance of the building in the public and within the police force. The sense of identity and value of the work of the police is welcomed by the individuals working at this station.

The importance of rail as backbone of public transport for all people but specifically for those with lower incomes is emphasized by the provision of a safe and secure environment, for which this building is one piece in the puzzle.

Awards:

CIFA Award of Merit 2007 - Inaugural recipient of the Gold Loerie Award for Three Dimensional & Environmental Design-Architecture.

The Aesthetics of Safety

- click images to see larger version -

THE AESTHETICS OF SAFETY

Location: Cape Town (2007)

Clients: Intersite / South African Rail Commuter Corporation / Metrorail.

SITUATION:

Rail is the accepted backbone of public transport in the Western Cape, contributing almost 59% of the total public transport profile, which in turn is responsible for 29% of the total transport profile in the city. The railway police force were disbanded during the late 1980’s after enduring allegations of acting as an enforcer for the apartheid regime, stricken by rumours of state sanctioned torture and other human rights abuses. The dissolution of this specialised police unit later proved to be a liability post 1994 with escalating crime on trains and at various train station stations, including vandalism, aggravated robbery, and violent assaults etc.

INTERVENTION:

The reintroduction of the Railway police was deemed necessary after a series of brutal incidents, but had two distinct social challenges facing its renaissance; countering the stigma of the past which still resided within living memory of many, and secondly using their reintroduction to connect different parts of the city and its different socio economic conditions and peculiar needs.

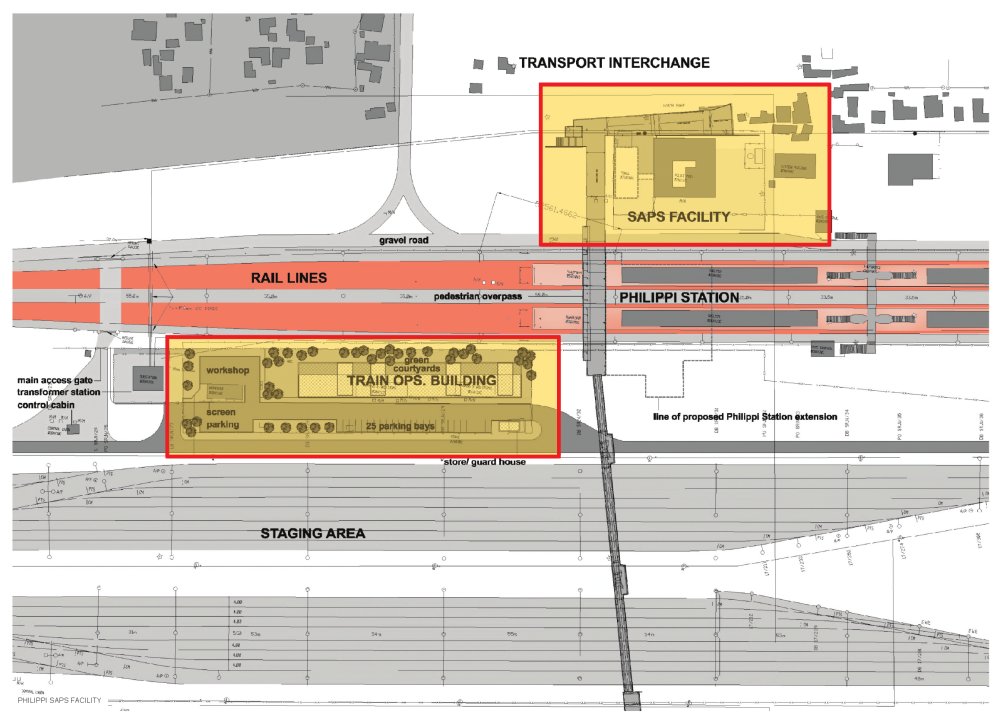

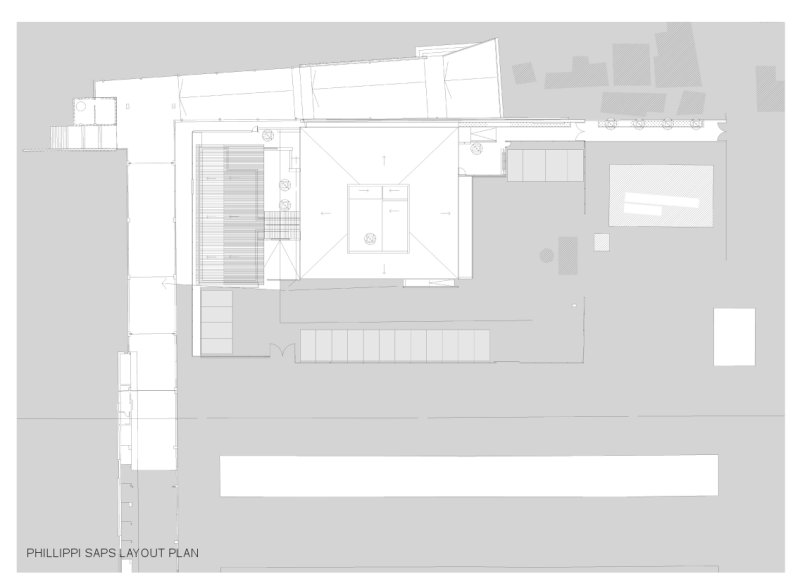

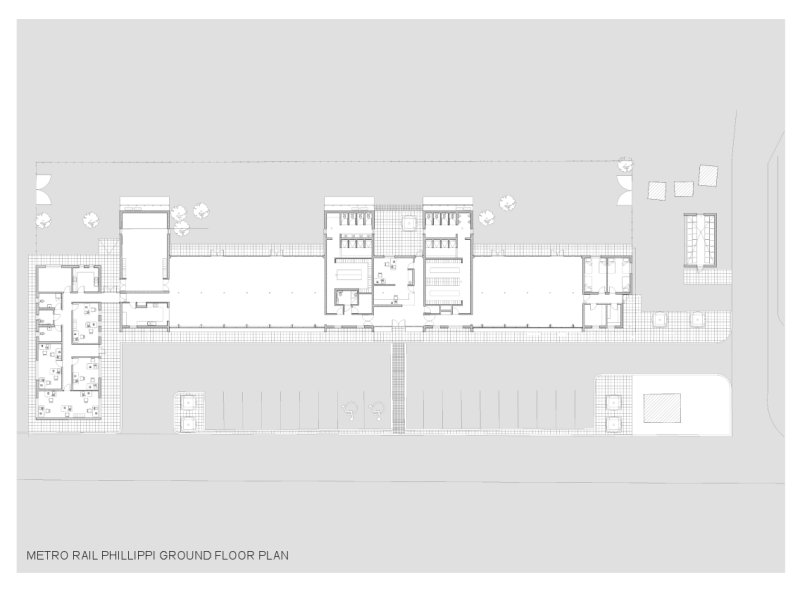

Four stations were identified, a new central hub at Cape Town station, and three satellite facilities, dealing with different degrees of social informality and contradictions, namely Philippi, Bellville and Retreat. All three satellites were located on the doorstep of taxi ranks and informal markets and meant to project a sense of the presence of the state apparatus in addressing safety for commuters. The police would be allocated to trains along various routes and thus connect the periphery to the core through a new web of security and visible policing.

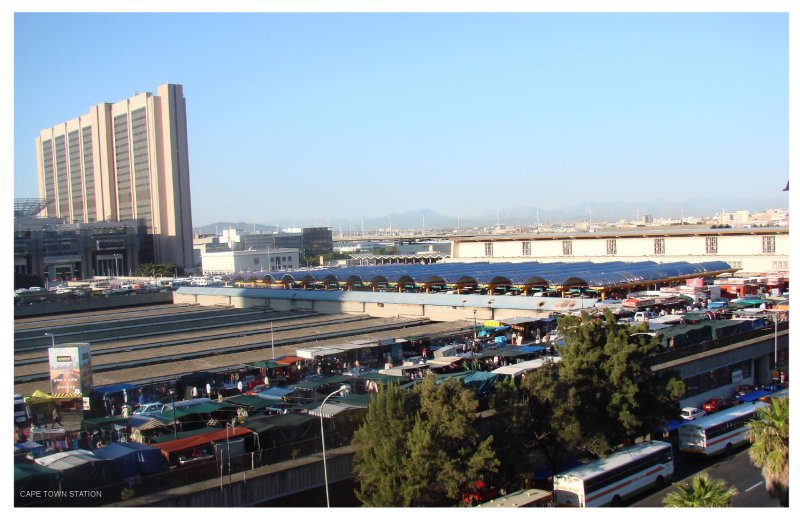

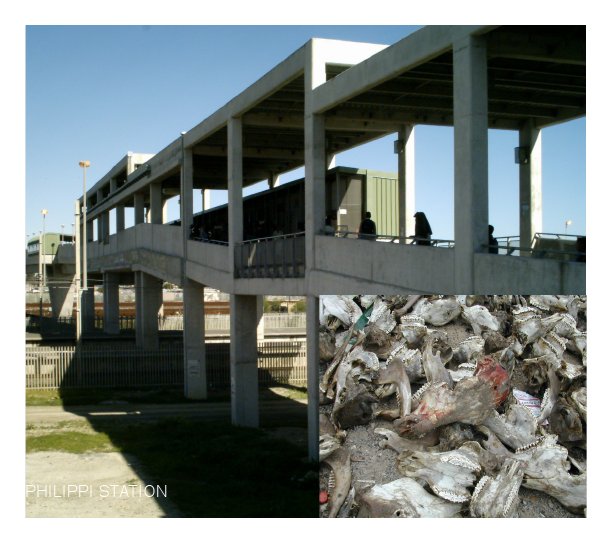

Bellville taxi rank remains one of the largest taxi ranks in the Cape peninsula exposed to increased levels of vulnerability to unrest, and protests from the taxi community, and informal sector. Philippi station was located close to a well known meat market, with various health and security challenges relating to food production, high levels of unemployment. Cape Town station as the nexus of the railway police stations had to engage with its role in the heart of the CBD and the largest informal market- which was responsible for 70% of the crimes reported in the city.

Unlike other development processes in which public participation would form an integral component of the delivery of public infrastructure, security processes precluded this. What rather followed was an intense engagement and education of various security experts in the art of environmental design as an enabler of safer communities and to re-instill pride within the police service.

HYPOTHESIS:

Can a ‘re-imagination,’ of the aesthetic of the police station shift behavioural patterns and ‘re-brand,’ the police? The design strategy undertaken involved re-imagining the architectural expression of the police station as typology into an opportunity to shift the social brand of the police; for the public and police persons. Ensuring the architecture heralded the transition from a police force to a service presented the space for a new logic for the interface of the architecture with place, culture and perception patterns. Every intervention was unique to its place and setting and offered a different exposure to context in all areas, crime reduction was significant and the public perception of the police improved.

Retreat station is well located from a rail perspective with a lower to middle class surrounding environment, with retail center and light industrial activity in the vicinity.

The building frames and completes the urban square which in turn contains the Retreat taxi rank, and the entrance to the railway station. It gives edge definition and mediates scale from its civic aspect and abutting residential fabric.

The project has met with great success from the user perspective, and substantiates the necessity for humanist discourse in the making of civic infrastructure. It has received an award from the Cape Institute of Architecture and received a gold medal in the category Communication Design at the 33rd Annual Loerie Awards in 2011.

The community has experienced heightened safety levels, the building is one of the most popular destinations for police staff, and has brought a renewed sense of civic purpose and pride. It re-establishes a role for architecture as a key component of urban clarity and performance.

MOKENA MOKEKA / HOLGER DEPPE

MAKEKA DESIGN LAB

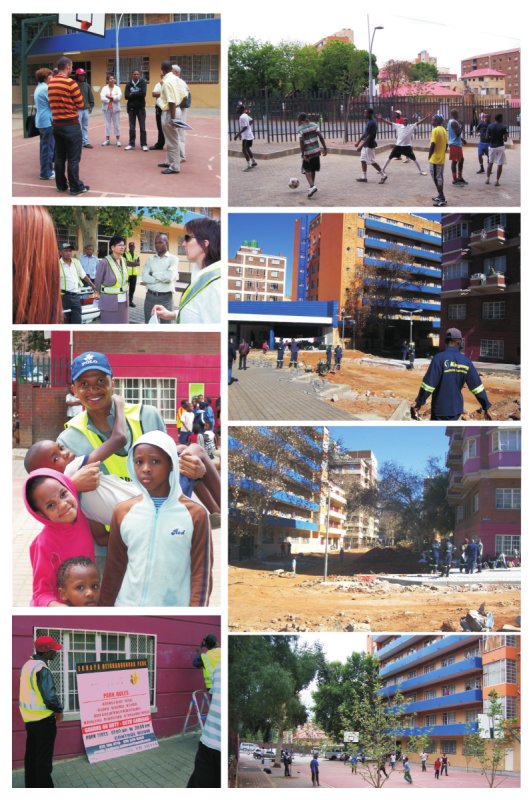

Urban Acupuncture - Khayelitsha

- click images to see larger version -

URBAN ACUPUNCTURE

‘The Needle and the (W)Hole.’

Location: Khayelitsha Cape Town (2007)

Design Consultants (phase two): City Think Space, ACG Architects and Development Planners

Clients: City of Cape Town and Khayelitsha community Trust

Khayelitsha is the largest and last township to be formally established in the Western Cape. Located at the heart of the Cape Flats and abutting Mitchel’s Plain, its narrative of dislocation, hope, and unequal access to resources, amenity and infrastructure positions the area as an exemplar of Apartheid informed informality. President Thabo Mbeki identified it as one of twenty national urban renewal nodes with a specific role to play in terms of social cohesion, upliftment and integration across the fractured cultural divide. The central business district was conceived to create a new urban room, an inspirational public realm for a devastated and desolate community lacking any resilient hierarchy of formalised ‘publicness.’

- click images to see larger version -

With competing voices of legitimacy, delivery of projects was hampered through indecision and lack of accountability between the state and social organisations. In a sense the informal landscape was mirrored by turbulent informal forces squabbling over the gaunt carcass of available resources. The noble intention of creating complementary CBD’s for each community (So called colored and Black African) has not been achieved despite the presence of catalytic interventions which anticipate and provoke the spontaneous creation of convivial environments through strategic urban design interventions. The informal condition in this instance could be described as a coded void or ‘hole,’ in the socio spatial geography of place.

Within this process, multi-purpose centers were identified as key urban markers for urban development, and encompass four components, a sports and recreation aspect, municipal offices and service point, heath and service clinic, and a library/arts and culture aspect. These later evolved into Thusong Service Centres.

- click images to see larger version -

As an outcome of a two year public participation process held by the City of Cape of Town to identify hierarchies of need for the community, the necessity for the sports component was identified as a priority and Makeka design Lab was commissioned to execute. The creation of a civic catalytic architecture in a context where the civic imperative is not a normative priority of the state presented challenges for officialdom, and the project seeks to relocate the discourse of architecture in informal conditions as part of a transformative act shaping township into town through bold design- architectural and urban. How does the needle stitch the (w)hole?

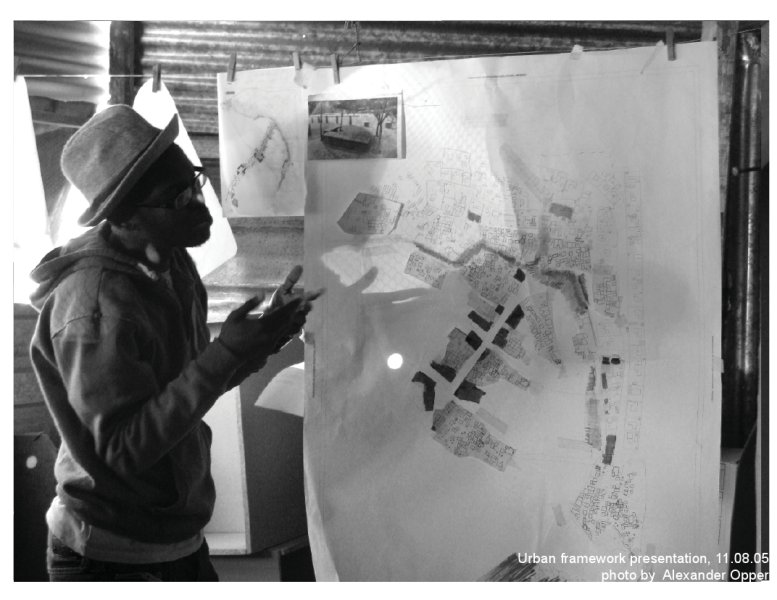

Urban Acupuncture - Khayelitsha (Panel 2)

URBAN ACUPUNCTURE

‘The Needle and the (W)Hole.’

Location: Khayelitsha Cape Town (2007)

Design Consultants (phase two): City Think Space, ACG Architects and Development Planners

Clients: City of Cape Town and Khayelitsha community Trust

The absence of any coherent and applicable urban design framework for the location of the buildings and its subsequent phases created the need to develop a self imposed conceptual urban design framework which would anchor the Architecture into a new public logic. Arising out of this commission, Makeka Design Lab was subsequently appointed by KCT to lead an interdisciplinary team to create an urban design framework which further addressed the imperatives of positive densification, alongside a mixed use urban identity with a renewed emphasis towards jobs creation, housing provision and an advanced understanding of sustainable human settlement.

The work identifies opportunities for sensitive infill, the exhibition reflects a participatory argument for presenting a vision for a community to aspire to. However patterns of institutional dysfunctional continue to constrain the process of becoming.

- click images to see larger version -

- click images to see larger version -

- click images to see larger version -

Back to Panel 1.

MOKENA MOKEKA / RIAAN STEENKAMP

MAKEKA DESIGN LAB

IN-SITU UPGRADING

Below is a brief excerpt from each of the projects in this category. Click on the links or image to see the full project panel details and illustrations.

Besters Camp

Exhibitor: Harber & Associates

To appreciate ‘Bester’s Camp’ one has to revert back to the terrible race riots that erupted in Durban during January 1949. Africans and Indians were at loggerheads, mainly in Cato Manor, a mixed race, dense settlement of shacks behind Berea and only a few kilometres from the colonial CBD.

These upheavals gave the freshly installed National government a chance to systematically implement Apartheid planning. Africans were relocated to a new township, Kwa Mashu, to the north and Indians to Chatsworth in the south of the city. During the mid 70’s another Indian township, Phoenix was located further to the north. The wide space between these towns was left vacant, an empty condone sanitaire separating different race groups.

eThekwini Municipality: Interim Services Programme

Exhibitor: eThekwini Municipality, Aurecon and Project Preparation Trust

Approximately a quarter of the eThekwini Municipality’s total population of roughly 3.5 million reside in informal settlements. Whilst the City can pride itself on a successful and large scale mass housing delivery programme, not all settlements can be provided with full services and low income housing in the short term due to funding and other constraints. Yet informal settlements face a range of basic challenges such as access to adequate sanitation, clean and safe energy and roads. As a result, a pro-active and broad based programme to provide a range of basic interim services to prioritized informal settlements within the Municipality was developed with a view to addressing a range of basic health and safety issues and delivering rapidly to as many settlements as possible instead of providing a high level of service to only a select few.

Home Improvements

Exhibitor: Finmark Trust

As soon as a subsidy beneficiary moves into their new house, thoughts turn to how to make it home. Cashbuild estimates that 60% of new units are upgraded within 18 months of the household moving in. In some cases, it’s a new window, or a fence; in others the entire house may be engulfed in a new structure. This building is incremental, step-by-step, financed with savings, microloans and sometimes even formal bank finance. In situ upgrading of the government subsidised house.

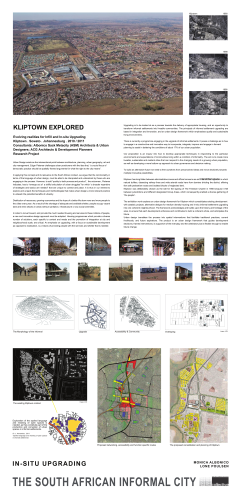

Kliptown Explored

Exhibitor: Monica Albonico and Lone Poulsen

Urban Design exists as the intersectional point between architecture , planning, urban geography, art and city management. Edgar Pieterse challenges urban practioners with the idea that, "a crucial focus of democratic practice should be spatially framed arguments for what the right to the city means".

In applying this concept and its relevance to the South African context, we argue that the commonality in terms of the language of urban design, must be able to be interpreted and understood by those who are engaging in the process. However, to add "quality to both process and producf, the outcomes, Pieterse indicates, has to "emerge out of a skillful articulation of urban struggles" for which "a broader repertoire of strategies and tactics are needed" that are unique to context and place. It is thus in our interest to explore and unpack the techniques and methodologies that make urban design a more relevant practice to unleash the potential benefits of urbanity.

Lion Park

Exhibitor: Michael Hart Architects Urban Designers

The location of the site is within the Municipal District of the City of Johannesburg (Region Al. The site is situated north of Randburg and approximately 40 km North West of the Johannesburg CBD. The site is 39 Ha in extent and is bounded by the K29, Malibongwe Drive to the west, the N14 Freeway 10 the north, the R28 to the south and 6th road to the east.

Bester's Camp

BESTER'S CAMP

eThekwini | 1990-current

Harber Masson & Associates

The Urban Foundation | Durban City Council

ORIGINS

To appreciate ‘Bester’s Camp’ one has to revert back to the terrible race riots that erupted in Durban during January 1949. Africans and Indians were at loggerheads, mainly in Cato Manor, a mixed race, dense settlement of shacks behind Berea and only a few kilometres from the colonial CBD.

These upheavals gave the freshly installed National government a chance to systematically implement Apartheid planning. Africans were relocated to a new township, Kwa Mashu, to the north and Indians to Chatsworth in the south of the city. During the mid 70’s another Indian township, Phoenix was located further to the north. The wide space between these towns was left vacant, an empty condone sanitaire separating different race groups.

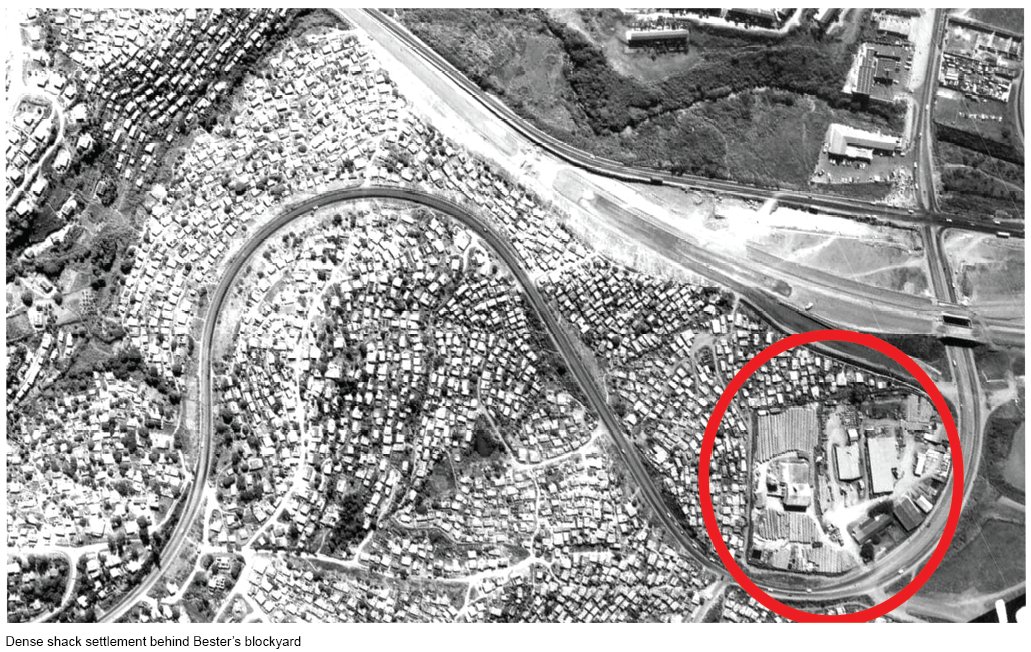

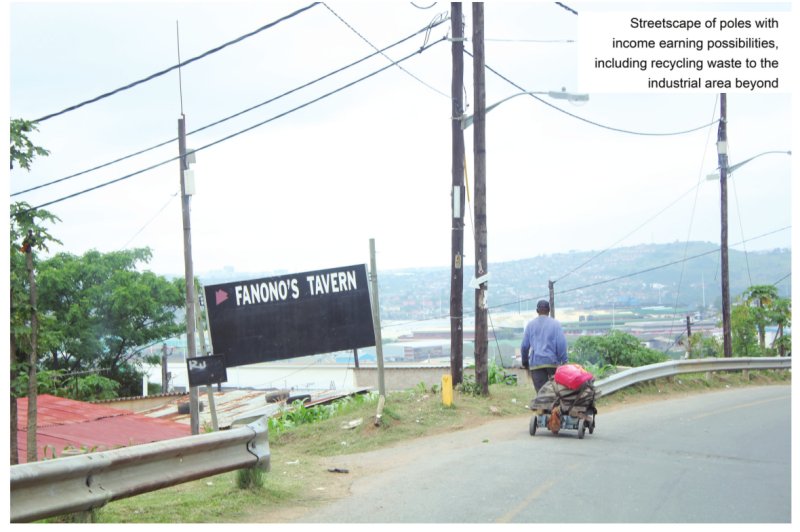

A Pretoria based construction company, Bester Construction, were the main contractors for Phoenix. They set up a blockyard on this vacant land, on the city boundary. As the spatial control of Apartheid began to diminish in the 80’s the steep hillside behind became settled by a dense informal settlement of makeshift shacks known as ’Bester’s Camp’.

This is an account of how a problem has been transformed into an opportunity!

TAKING STOCK

The Informal Settlement Division of the Urban Foundation was encouraged by the Durban City Council to resolve the situation during the late 80’s. Harber Masson and Associates were commissioned to unravel the situation. In total contrast to contemporary township delivery with their modernist approach, focussed on delivery at volume, efficiency and minimal liaison with the future inhabitants, Bester’s Camp involved an on-going negotiation with residents that were already established, right on the edge of the city. Residents valued the advantage of being relatively well located on a springboard into the controlled city. To insert services it was initially recommended that ten per cent of the houses would have to be relocated elsewhere. They refused.

This presented an enormous challenge. The high densities and lack of adequate funding meant that an incremental approach had to be taken – a process and not a product. In-situ upgrading was the only viable approach. To convey this approach, large models were made to demonstrate the process, to demonstrate commitment and to engender communal ‘ownership’ of the proposal. The first entitled ‘NOW’ accurately recorded the existing situation on a large portion of the site to the extent that residents could identify their shelters. The next titled ‘SOON’ illustrated the ‘quick wins’ or envisaged short term interventions to consolidate the situation – public water kiosks, roadways, hardening of paths, steps and especially the storm water drainage lines. The final model ’EVENTUALLY’ illustrated a dense, multi storey settlement on steep cross falls to provide a vision of the future. Amalfi in Italy was provided as precedent!

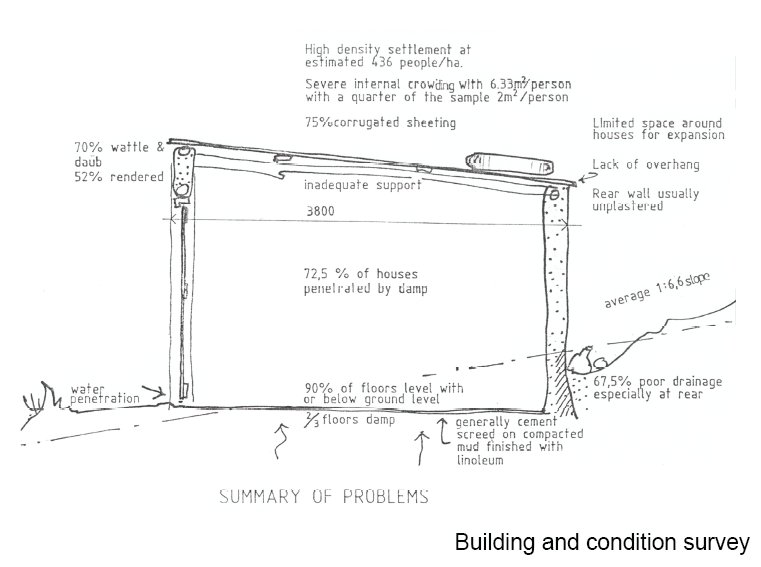

The next step was to undertake a detailed survey of a sample of about seven per cent of the stock of informal structures to reveal prevalent problems and opportunities in the construction and to document how these may have been resolved within local cost and availability constraints.

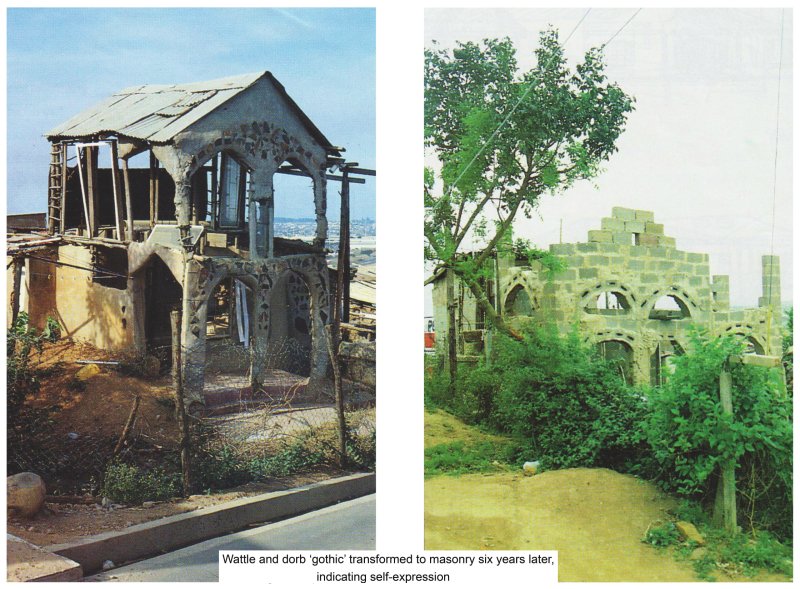

Inappropriate detailing causing damp in mud walls was the most serious shortcoming. Guidelines were issued on the importance of overhangs, raising the internal floor level and digging away the rear banks, all gleaned for excellent local examples of tyre retaining walls, use of vegetation to stabilise banks, recycled components such as windows and various shuttering systems to form walls filled with inorganic waste. Jap panels, the local name for the plywood sides to crates from the Toyota assembly plant, were particularly revealing. Double storey houses were recorded built entirely of these, including the roofing. Here an acute awareness of the properties of materials was evident because plastic sheeting was draped over the top with a final sacrificial layer of Jap panels to protect it from deterioration from the sunlight.

It is remarkable how informative indigenous solutions can be. To this day Harber’s home in Durban has ceilings of Jap panels, recycled waste, at a fraction of the cost of a conventional solution.

Continued on Panel 2

.

RODNEY HARBER

Bester's Camp (Panel 2)

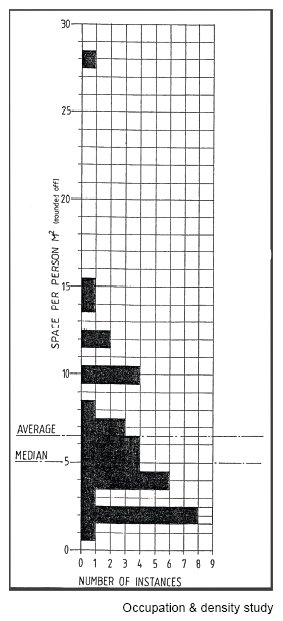

Another component of this detailed investigation was to measure up all the building stock on one hectare ofland including the interior living arrangements. It was revealed that 28% of the land was already built on, very high for a relatively steep site and particularly high for a layout composing freestanding units. The average site size was only 104sqm!

Occupational density, the total area of habitable rooms/occupants is a keen indicator of overcrowding. Here it proved to be dangerously high at 6.33sqm per resident. Five square metres is generally accepted as the minimum but in this sample the lower quarter averaged 2sqm per person or less - little more than a bed - with the severest case at 1.3sqm. At this level it implied that all floors were covered by bedrolls at night with minimal privacy. The average shelter had six residents and 2.5 habitable rooms. Many rooms were very simply curtained for further privacy.

Interpolating these figures revealed a very high density of 436 people per hectare and a total population of up to 35000 residents. Importantly, pedestrian access was also an accepted norm.

CONSOLIDATION

By then , the block yard had ceased to exist, leaving a well secured vacant site for the city to acquire communal buildings. This presented a golden opportunity, and the space eventually housed central offices , a hall, library, primary school, market stalls and service depots. The Urban Foundation established offices there as well.

All sites were pegged and surveyed after a drawn out and laborious process of initially placing wooden pegs on all corners after mutual agreement be all neighbours, generally after office hours. This process sent a signal of potential security of tenure which resulted in a flurry of upgrading by residents themselves. Hygiene was an important consideration at such high densities. Since water still had 10 be carried to each site , waste water was generally spread onto the vegetation. Initially every site had a masonry, ventilated pit latrine built on the edge and lined up wherever possible for subsequent pipelines. Electricity was supplied via prepaid meters, from a forest of overhead wires on poles that generally also served as street lighting. This all brought about a profound transformation in living conditions.

THE BUILDING PROGRAMME

Funding eventually became available for each resident to have the equivalent of a 16sqm masonry room built onto their existing house or as a freestanding unit. The Urban Foundation devised a computer programme consisting of the names of approved beneficiaries and the subsidy amount credited to them. Thereafter local hardware shops tendered to provide packages of basic materials and to deliver them as close to sites as possible when called for. They had to allow for five such deliveries to each site. The materials would then be paid for monthly from the central fund and the allocation of each beneficiary reduced .

This unleashed a flurry of construction by local contractors who had their labour costs settled at agreed rates based on output. Owners could also draw down their allocation with materials to improve existing houses. Numerous 'building inspectors' were available to approve proposals in situ, offer advice and to approve payments. Once again this was a drawn out process which maximised possibilities of individuality, treating each beneficiary and site as a unique element.

LESSONS LEARNT

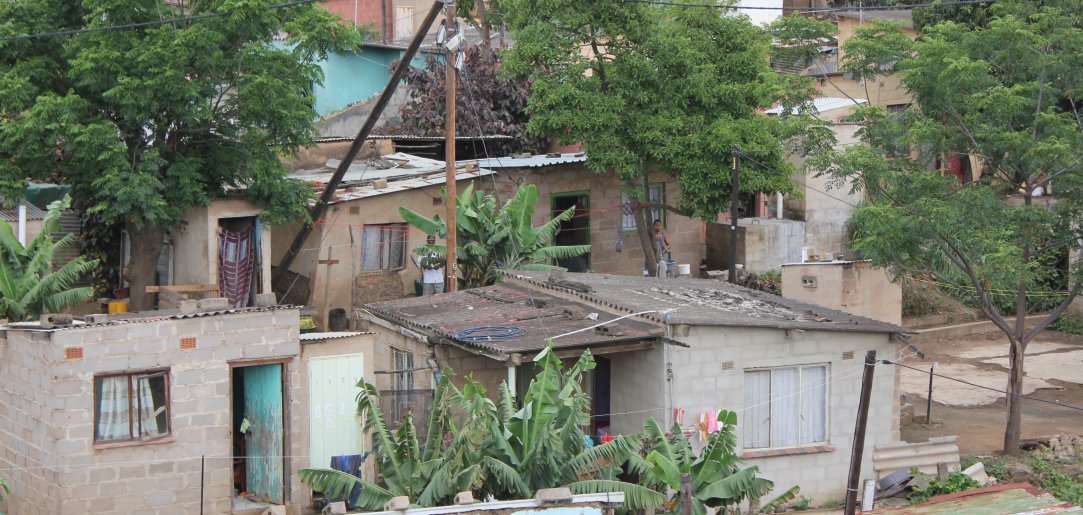

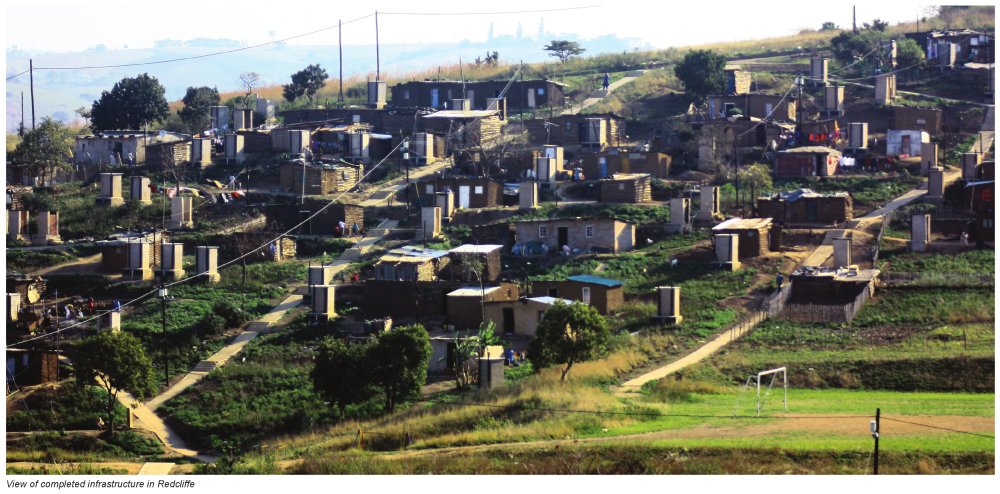

Due to community involvement, Bester's is a high density settlement with mainly pedestrian access, situated near a variety of public transportation links and, most importantly, is visually stimulating due to the variety of building solutions - with most of the elevations being visible due to the steep terrain. Sub-tropical vegetation also unifies the vista and consolidates the soil.

All this results from IN-SITU UPGRADING, a people-centred approach which searches for, and responds to , the unique characteristics of every site.

Two decades ago there were half a dozen housing delivery methods to respond to. Now we simply have RDP layouts and some social housing from the public domain. The reasons are clear compared to the Modernist paradigm which has subsequently gripped our housing delivery in South Africa. Straight lines, identical delivery at volume, full services, overall control , annual budgets and, ultimately, dissipated responsibilities. The model is Service, Build then Occupy.

This is inverted in In-situ Upgrading. To Occupy is paramount - inevitably in a good location. As security of tenure is perceived, the Build consolidation phase ensues followed by Service. Instant shelter! Consider the advantages of the building process alone. Dozens of small time , labour-only contractors have been set up and continue to operate in the surrounding areas.

Housing authorities shy away from this people centred approach because it is drawn out and never has a fixed exit date. Budgets are perceived to be problematic and it also involves tedious community involvement, after office hours! Grand control appears to be relinquished!

Back to Panel 1

.

RODNEY HARBER

Home Improvements

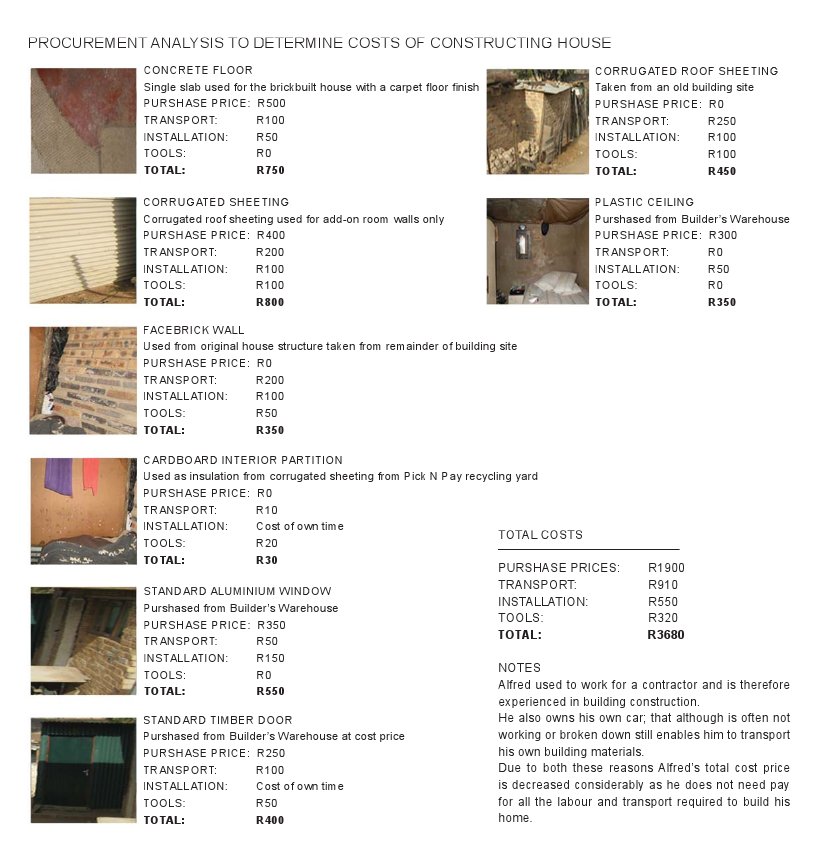

HOME IMPROVEMENTS

One Brick at a Time | Findings from the Visible Investment Survey

Finmark Trust

As soon as a subsidy beneficiary moves into their new house, thoughts turn to how to make it home. Cashbuild estimates that 60% of new units are upgraded within 18 months of the household moving in. In some cases, it’s a new window, or a fence; in others the entire house may be engulfed in a new structure. This building is incremental, step-by-step, financed with savings, microloans and sometimes even formal bank finance. In situ upgrading of the government subsidised house.

In 2010, the FinMark Trust, with support from Urban LandMark, the National Department of Human Settlements, the South African Cities Network, the Western Cape Department of Human Settlements and the FB Heron Foundation, undertook a study into the performance of government subsidised housing units. The study included a visual investment survey, in which the process and extent of home improvements was explored in three governmentsubsidised housing settlements: Slovoville, in Soweto, Gauteng; Emaplazini, in Inanda, KwaZulu Natal; and Thembalethu, in George, Western Cape. All of these settlements are more than ten years old.

The settlements

Slovoville (Soweto, Gauteng) was one of the first subsidy developments in Soweto and was built in the late 1990’s. It has approximately 1600 subsidy houses. Most beneficiaries came from Soweto and went through a long politically driven process of attending weekly meetings until they secured their subsidy houses. The area was officially opened by Mr Nelson Mandela.

Emaplazini (Inanda, Kwazulu Natal) is a subsidy development built in Inanda on a mountainous area. It has approximately 1000 houses. Beneficiaries squatted on farmland for many years and government bought the land from the farmers in the late 1990’s. A community organization was formed to negotiate a people’s housing process development. Interested community members participated in the organization by contributing 50 cents per day to a savings plan – over time, this led to their being able to build 4-bedroomed houses, which they paid for over a 5-year period. Those community members that did not participate in the community savings plan received subsidy houses.

Thembalethu (George, Western Cape) was developed in the late 1990’s, early 2000’s in a township close to George. It has approximately 5000 houses. The allocation of subsidy houses focused on informal settlement dwellers in Thembalethu. Other beneficiaries moved from the Eastern Cape and other rural areas in the Western Cape to try and find work in George or surrounding areas.

Findings

The majority of houses in the three settlements had been improved upon. More than 95% of houses in Slovoville and Thembalethu showed some form of investment. In Emaplazini, 77% showed some form of investment.

The majority of houses had a small investment in the form of plaster, paint, porch, burglar bars, shack or wire fence. The estimated value of this investment is less than the value of the original subsidy house. A significant number of houses had investments that looked as though they would have doubled, or more than doubled the value of the original subsidy house. The extent of this varied across the areas but it is most significant in Slovoville where over half (52%) had medium, big or very big investments. This is lower in Thembalethu (27%) and Emaplazini (28%). In all the areas there was some indication that investment is planned, with stockpiled building materials visible from the street.

The study found that investments seemed to be independent of the surrounding environment, and not as a result of state or private sector investment in the area. Respondents suggested that their motivation for making investments arose from the scarcity of other, more suitable housing. In the absence of a formal housing market catering for their specific needs, they needed to improve their housing incrementally. In some ways, therefore, home improvements are an informal response to housing supply constraints – households opt to extend or otherwise improve their housing because the market is not supplying any other form of affordable housing. In each of the neighbourhoods studied, and indeed across South Africa, the once uniform neighbourhoods of RDP housing side-by-side are now showing tremendous diversity in house type and form. A well-invested 4-bedroom house can be found in between two original subsidy houses that have been left untouched. Subsidy houses with no investment can be found on tarred roads, and subsidised houses transformed into mansions can be found on gravel roads. There is no format or pattern. There are no ‘wealthy streets’ and ‘poor streets’.

Continued on Panel 2

.

FINMARK TRUST

Home Improvements (Panel 2)

Case study | The joy of investing into a subsidy house

Jeanette and her husband Lumic relocated from Graff Reinet to George in 1992 searching for better job prospects. In 1979 Lumic put his name on a housing list for a site. In 1993 they moved onto their site, which had a toilet and built a 4-roomed bungalow made of wood planks to live in. There was no electricity supply or running water. Finally in 1995 they moved their bungalow to a different part of the property and for three weeks watched as their subsidy house was finally constructed. They received the Title Deed to their property a few months after the house was completed.

In 2010, Jeanette and Lumic decided to remodel and improve their house. They took two personal loans from Standard Bank and First National Bank for R30 000, and then used another R25 000 of their own savings to finance the construction. Lumic is a full time employee of the Coca-Cola Company; he needed his pay-slip, ID document and bank statements to acquire the loan. Jeanette is a member of a stokvel. Although the building materials were bought incrementally, the remodeling of the house was completed in three weeks during February 2010.

The current house will be inherited by their youngest son thus they will never consider selling the house. The son currently occupies the original wooden bungalow they lived in before their subsidy house was built. As a family, they enjoy the freedom and independence that comes with being homeowners.

Case study | The story of a 35m2 starter house

The respondent we interview describes herself as a woman who has more faith in the dreams she has in the daytime. “You can’t trust the dreams you have at night when you are sleeping”.

There is no telling what her dreams were when she went to write her name on the housing waiting list or when, at the community meetings, the older men teased her suggesting she was too young to own a house thus would not qualify. However, regardless of her youthful looks, she was a single mother earning less than R 3500 per month and qualified to be among the first (along with the elderly) to be allocated a new home. Now her property boasts the original subsidised house, a container from which she runs a spaza shop, and two formally built backyard rooms, all with formal ablutions.

Patience moved to Slovoville in 1997. However, for nine years she continued to work in Silvertown faithfully making the commute each day. She also sold sweets during this time using the additional income to supplement the extra transportation costs that accompanied the move to her new RDP home. An inspiring story unfolds to reveal sheer determination, strength of character and hard work.

The rooms and spaza shop are both projects that were completed incrementally and yet they both grew simultaneously alongside the other. The rooms, needing much more capital than the spaza, and were built with a combination of stokvel savings, micro loans, building materials from Builder’s Warehouse and leaps of faith. The rental she received allowed her to take on an additional micro loan to build up her business and buy stock for the spaza shop. And the green container, on the other hand, is what she used to turn it into a spaza shop and sell small grocery items to her neighbours. She sees herself as having no other option in pursuing this avenue because she fears she will not find a job elsewhere. She hopes her efforts will leave an indelible impression on her daughters.

Today she is well respected among her peers, family and neighbours and especially her customers- the children who come and buy from her spaza shop. Her entrepreneurial spirit is inspiring. It has led her to take on financial risk with the micro loans she has acquired to establish a spaza shop and built the backyard rooms, which now house two tenants.

“An RDP house gives you the opportunity to use your mind and brains to make decisions for you and your family.”

“It is a shelter that gives you space to think and freedom to plan the future.”

“It is a start. It is one small thing, but this thing I like very much.”

Back to Panel 1

.

FINMARK TRUST

Kliptown Explored

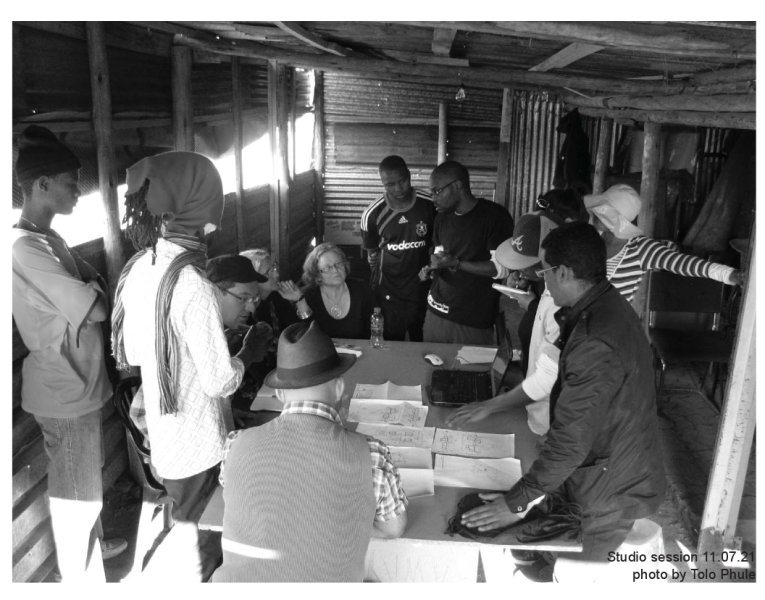

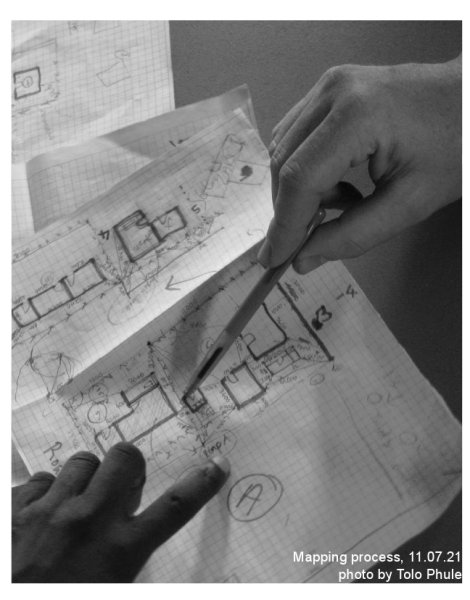

KLIPTOWN EXPLORED

Evolving realities for Infill and In-situ Upgrading Kliptown . Soweto . Johannesburg. 2010 I 2011

Consultants: Albonico Sack Metacity (ASM) Architects & Urban Designers; ACG Architects & Development Planners

Research Project

Urban Design exists as the intersectional point between architecture , planning, urban geography, art and city management. Edgar Pieterse challenges urban practioners with the idea that, "a crucial focus of democratic practice should be spatially framed arguments for what the right to the city means".

In applying this concept and its relevance to the South African context, we argue that the commonality in terms of the language of urban design, must be able to be interpreted and understood by those who are engaging in the process. However, to add "quality to both process and producf, the outcomes, Pieterse indicates, has to "emerge out of a skillful articulation of urban struggles" for which "a broader repertoire of strategies and tactics are needed" that are unique to context and place. It is thus in our interest to explore and unpack the techniques and methodologies that make urban design a more relevant practice to unleash the potential benefits of urbanity.

Distribution of resources, growing economies and the hope of a better life draw more and more people to the cities every year. As a result of the shortage of adequate and available shelter, people occupy vacant land and erect shacks in areas without sanitation, infrastructure or any social amenities. In order to move forward , and provide the much needed housing and services to these millions of people, a new and innovative design approach must be adopted. Housing programmes which provide a diverse number of solutions, each specific to context and needs and the promotion of integration at city and neighbourhood scale, are critical. An emphasis on upgrading, with a focus on sustainable development as opposed to eradication, is a means of providing people with the services and shelter that is needed.

Upgrading is to be looked at as a process towards the delivery of appropriate housing, and an opportunity to transform informal settlements into liveable communities. The principals of informal settlement upgrading are based in integration and innovation, and an urban design framework which emphasises quality and sustainable living environments.

There is currently a programme engaging in the upgrade of informal settlements. It poses a challenge as to how to engage in a constructive and innovative way to incorporate , integrate, improve and engage in forward planning to assist in bettering the conditions of about 17% of our urban population.

Our proposition is an inquiry into how to develop appropriate techniques in responding to the particular environments and expectations of communities living within a condition of informality. The aim is to create more liveable , sustainable and resilient cities that can respond to the changing needs of a growing urban population, as well as developing a more bottom-up approach to urban governance and decision making.

To build an alternative future we need to free ourselves from preconceived ideas and move decisively towards multiple innovative possibilities.